In 1954, archaeologist Samuel Lothrop described the horror show of an ancient burial site he'd excavated in Panama.

Hacking, mutilation, sacrifice, people buried alive, cannibalism, flesh stripped from bones, decapitation for the purpose of trophy-taking - it was all there.

Since then, the paper has been cited over 35 times as evidence of the culture's savagery. But there's one huge problem: the evidence for it simply doesn't exist.

That's according to archaeologists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, who have conducted a long-overdue review of the remains, the evidence, and the paper. They've concluded that the bones show no evidence of trauma at or near the time of death.

Lothrop's claims aren't just exaggerated, in other words - they appear to be completely unsupported by the physical evidence.

The cemetery at the archaeological site of Playa Venado, or Venado Beach, in Panama was excavated by Lothrop and his team in 1951.

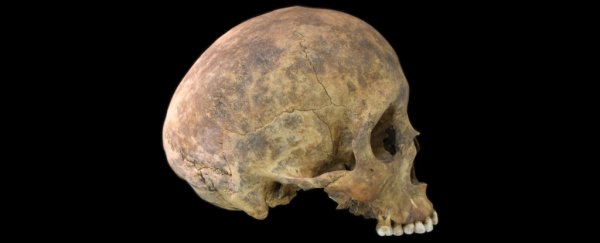

From the site, which dates to between 550 and 850 CE, they recovered 202 skeletons and grave goods, with additional 167 skeletons recovered by other archaeologists at later times.

The paper, titled "Suicide, sacrifice and mutilations in burials at Venado Beach, Panama," set the tone for much of the work that followed. In it, Lothrop, who worked at Harvard University's Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, asserted that the manner in which many of the bones had been found was indicative of violence.

But his paper is indicative more of the times than of shoddy work. Bioarchaeology wouldn't be established as a specialisation for another two decades.

And it was Lothrop's careful documentation and preservation of the remains that allowed researchers to review his work - he sent the skeletons of 77 individuals to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History for evaluation, where they've remained to this day.

Archaeologists Nicole Smith-Guzmán and Richard Cooke believe that Lothrop's account was coloured by the accounts of 16th century Spanish conquistadors, who had a vested interest in making the people of South America seem as savage and uncivilised as possible.

"We now realise that many of these Spanish chroniclers were motivated to show the indigenous populations they encountered as 'uncivilised' and in need of conquering," Smith-Guzmán said.

"Rather than an example of violent death and careless deposition, Playa Venado presents an example of how pre-Columbian societies in the Isthmo-Colombian area showed respect and care for their kin after death."

The researchers examined the 77 skeletons at the Smithsonian, as well as archival documents and photographs, as well as documents and photos from official and unofficial excavations at the site. These include field notes, drawings, correspondences and writings.

They also studied ethnohistorical accounts by early Spanish chroniclers describing their interactions with the indigenous populations of Central America at the time of European contact.

On examination of the bones, the only wounds Smith-Guzmán found were healed long before death, including blows to the head, and a dislocated thumb, and only one showed evidence of trauma related to interpersonal violence.

Lothrop's evidence for perimortem violence - occurring around the time of death - was primarily focused on the manner in which the bones were found. Open mouths, he said, were evidence of having been buried alive (you can find this repeated on Wikipedia); separated vertebrae were evidence of trauma.

The researchers believe that much of the evidence points to secondary burials - the preservation of the remains of important individuals to be interred at a later date - and disturbances indicating graves were reopened to inter newly dead individuals with those who had already been buried for some time.

"The uniform burial positioning and the absence of perimortem (around the time of death) trauma stands in contradiction to Lothrop's interpretation of violent death at the site," Smith-Guzmán said.

"There are low rates of trauma in general, and the open mouths of skeletons Lothrop noted are more easily explained by normal muscle relaxation after death and decay."

Their findings tally with other accounts of burial practices in pre-Columbian and colonial Panama, rather than a bloodthirsty culture of violence, sacrifice and cannibalism, the researchers said.

Their paper has been published in Latin American Antiquity.