We may have been overestimating the role of a pathological class of misfolded protein in neurodegenerative disease.

Called prions, these molecules are responsible for conditions such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy or 'mad cow disease', chronic wasting disease in deer, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

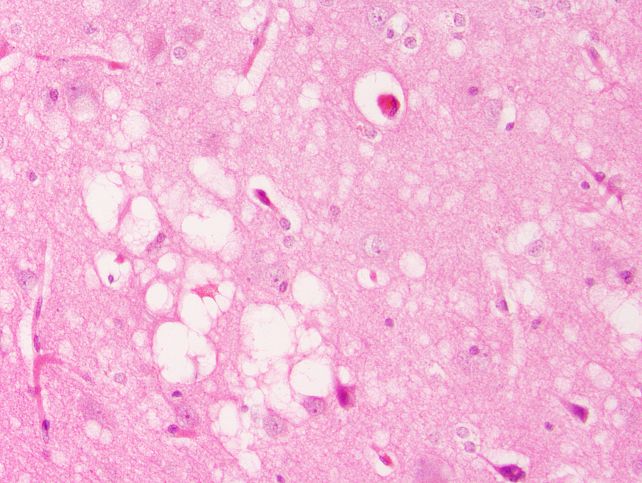

A new study in mice has found that some of the hallmarks of prion disease in brain tissue – such as the appearance of sponge-like holes, scarring, and accumulation of amyloid plaques – can develop even in the complete absence of prions in their infectious configuration.

Related: Misfolded Proteins Could Make Dementia Transmissible, Scientists Suggest

Instead, the study found that non-infectious prion precursors in the presence of chronic inflammation driven by a bacterial endotoxin were enough to trigger prion-like neurodegeneration.

This finding suggests we have overlooked some of the mechanisms that contribute to prion diseases, and in some cases, even mistaken the underlying cause. It also has implications for prion-like conditions such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS, in which misfolded proteins are central to irreversible brain damage.

Prion diseases – found in humans – are the terrifying result of a normal biological process going randomly awry.

Proteins consist of sequences of amino acids precisely folded to perform specific functions. They don't always work quite as intended, though; cells make wonky, misfolded, non-functional proteins all the time. Your body is also pretty good at unfolding or destroying the wonky proteins when this happens.

On extremely rare occasions, however, some types of misfolded protein can become a prion. Not only do they not function as they should, but these oddly-shaped proteins also force other proteins to adopt the same misfolded shape. Worse still, they resist the body's protease clean-up mechanisms, allowing them to accumulate and destroy cells.

Think of a cog with a bent tooth; every cog it interlocks with also ends up with a bent tooth, which it then passes on to its adjacent cogs, and so on. The result is an unstoppable spread of dysfunction. What makes it even more horrifying is that prions are, by definition, infectious; they can be spread between individuals, most commonly by consuming prion-contaminated meat.

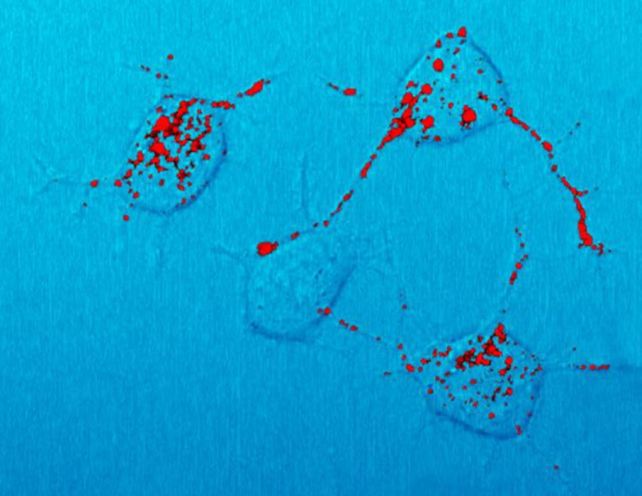

Proteins that can turn into prions are called prion proteins, or PrPC. A misfolded PrPC doesn't have to become a prion – that's a very specific, infectious type of misfolding – but recent evidence suggests that the other, non-infectious ways PrPC can misfold may also trigger neurodegeneration.

Other emerging evidence suggests that a bacterial endotoxin called lipopolysaccharide (LPS), found on the outer membranes of some bacteria, can accelerate prion disease by inducing protease resistance in prion proteins. It also activates the host immune system's inflammatory response, further contributing to neurodegeneration.

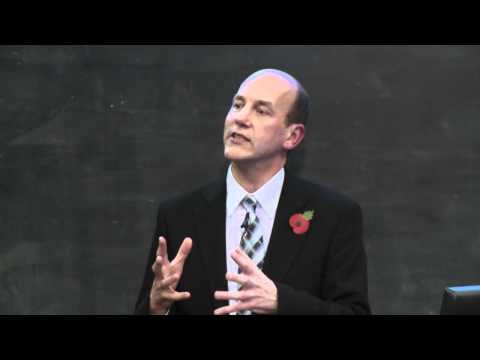

Led by immunologist Burim Ametaj of the University of Alberta in Canada, a team of researchers used transgenic mice to determine the contribution of misfolded, non-infectious PrP and chronic inflammation to prion-like neurodegeneration.

They artificially generated a misfolded form of a PrP that is toxic to neurons without being infectious.

Then, they divided their study mice into six groups.

The first group was given only saline – that was the control group. The second group was administered LPS, and the third group the toxic, misfolded, non-infectious PrP. The fourth group received both. The fifth group received actual infectious prions, and the sixth group received prions and LPS.

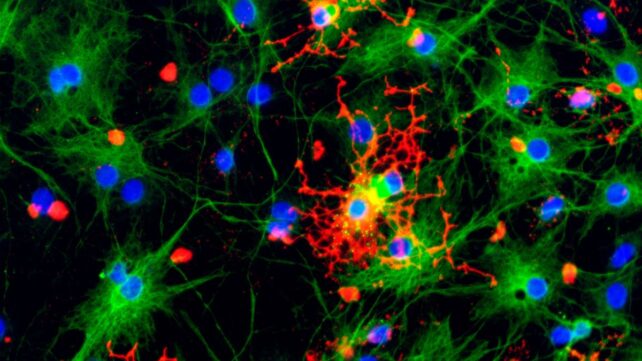

Then, the researchers carefully monitored and tested their mice for up to 750 days, studying their brains for spongiform changes, protease resistance, a type of brain scarring called astrogliosis, and amyloid plaques – all of which are associated with prion disease.

The group that was given just the misfolded, non-infectious PrP alone developed the spongiform brain damage and scarring, but not the protease-resistant PrP that defines infectious prions. Meanwhile, the LPS-only group developed amyloid plaques, spongiform damage, and a high 40 percent mortality rate – but again, no protease resistance.

Combining LPS with the non-infectious PrP misfold did not increase lethality, but holes in the brains of mice in this group did grow larger. Finally, combining the prion with LPS dramatically accelerated the course of the disease. All of the mice in this group died within 200 days.

"This fundamentally challenges the prevailing theory that these types of brain diseases are only about prions or similar misfolded proteins," Ametaj says.

The results suggest that, in at least some prion diseases, the host may first be weakened by inflammation before the protein misfolding that leads to prion formation – that prion disease may not actually start with prions, but with inflammation, or the non-infectious, misfolded PrP.

The Alzheimer's-like presentation of the mice administered only with LPS has some interesting implications. It suggests that inflammation may play a key role in kicking off neurodegenerative, prion-like diseases – echoing other recent studies that have found links between inflammation and Alzheimer's disease.

"It opens up an entire anti-inflammatory medicine toolkit. Bacterial endotoxins have been found in the brains of Alzheimer's patients, so risk factors that reduce dementia – exercise, anti-inflammatory diets, gut health, metabolic health – might work partly by reducing endotoxin burden," Ametaj says.

"These diseases are complex, but if endotoxin exposure contributes to even 20 to 30 per cent of cases, controlling this modifiable risk factor could spare millions of people. We might prevent some neurodegenerative diseases the way we prevent heart disease, by managing inflammatory risk factors throughout life.

"In a field where there's been little hope, that matters."

The research has been published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.