A newly proposed propulsion system could theoretically beam a heavy spacecraft to outside the confines of our Solar System in less than 5 years – a feat that took the historic Voyager 1 probe 35 years to achieve.

The concept, known as 'pellet-beam' propulsion, was awarded an early-stage US$175,000 NASA grant for further development earlier this year.

To be clear, the concept currently doesn't exist much beyond calculations on paper, so we can't get too excited just yet.

Still, it's attracted attention not only because of its potential to get us into interstellar space within a human lifetime – something that traditional, chemical-fueled rockets can't – but also because it claims it can do so with much larger crafts.

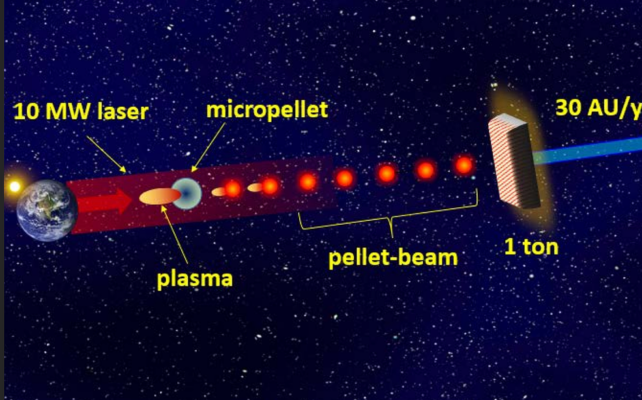

"This proposal examines a new propulsion architecture for fast transit of heavy (1 ton and more) payloads across the Solar System and to interstellar medium," explains the lead researcher behind the proposal, aerospace engineer Artur Davoyan from the University of California, Los Angeles.

The pellet-beam concept was partly inspired by the Breakthrough Starshot initiative, which is working on a 'light-sail' propulsion system. With the help of millions of lasers, a tiny probe would theoretically be able to sail to neighboring Proxima Centauri in just 20 years.

The new proposal starts with a similar idea – throw fuel at a rocket instead of blast it out of one – but it looks at how to shift larger objects. After all, a small probe isn't necessarily what we need if we want to one day explore, or colonize, the worlds outside our Solar System ourselves.

To work, the conceptual propulsion system requires two spacecraft – one that sets off for interstellar space, and one that goes into orbit around Earth.

The spacecraft orbiting Earth would shoot a beam of tiny microscopic particles at the interstellar spacecraft.

Those particles would be heated up by lasers, causing part of them to melt into plasma that accelerates the pellets further, a process known as laser ablation.

Those pellets could reach 120 km/second (75 miles/second) and either hit the sail of the interstellar spacecraft or repel a magnet within it, helping to propel the spacecraft to huge speeds that would let it whizz out of our heliosphere – the bubble of solar wind around our Solar System.

"With the pellet-beam, outer planets can be reached in less than a year, 100 AU [astronomical unit] in about 3 year and solar gravity lens at 500 AU in about 15 years," says Davoyan.

For context, an AU, which stands for 'astronomical unit', roughly represents the distance between Earth and the Sun, or around 150 million km (93 million miles).

It took the Voyager 1 probe 35 years of travel to cross into interstellar space back in 2012, at roughly 122 AU away.

According to the current projections, a pellet-beamed spacecraft weighing 1 ton could do the same in under 5 years.

Davoyan explained to Matt Williams from Universe Today back in February that his team has taken the pellet approach, rather than simply using lasers like other sail projects, because the pellets can be propelled by relatively low-power lasers.

In their current projections, only a 10-megawatt laser beam could be used.

"Unlike a laser beam, pellets do not diverge as quickly, allowing us to accelerate a heavier spacecraft," Davoyan told Williams.

"The pellets, being much heavier than photons, carry more momentum and can transfer a higher force to a spacecraft."

Of course, all of this is pure speculation for now. But the Phase I of NASA's Innovative and Advanced Concepts (NIAC) grant will help.

The project was one of 14 that were funded at this early stage, and the next step will be to show proof of concept using experiments.

"In Phase I effort we will demonstrate feasibility of the proposed propulsion concept by performing detailed modelling of different subsystems of the proposed propulsion architecture, and by performing proof of concept experimental studies," says Davoyan.

We'll be following the progress closely.