Scientists searching for signs of seasonal storms on Titan have finally found the smoking gun. A slick shimmer spotted on the north pole of the Saturnian moon is the first evidence of rainfall in the hemisphere - the start of summer in the north.

It's the evidence astronomers have been waiting years to see, since Cassini's arrival in Saturn's orbit all the way back in 2004.

When the probe reached Saturn, it was summer on the moon's southern hemisphere, and scientists were eagerly watching for signs of seasonal changes. This is because, although Titan itself is rather different from Earth, its climate is similar to ours in many ways.

A day on Titan is 15.9 Earth days - the same length as its orbit around Saturn, because it's tidally locked, just our own Moon. A year is 29.5 Earth years. Titan's axial tilt is about 27 degrees, compared to Earth's 23.5-degree tilt.

So a season on Titan lasts on average roughly 7.5 Earth years (although they do vary because of Saturn's orbital eccentricity, making northern summers and southern winters longer than the reverse).

The spring equinox fell in 2009, and in 2011; atmospheric changes were interpreted as the onset of southern winter. But rains expected in the north remained elusively undetected.

"The whole Titan community has been looking forward to seeing clouds and rains on Titan's north pole, indicating the start of the northern summer, but despite what the climate models had predicted, we weren't even seeing any clouds," said physicist Rajani Dhingra of the University of Idaho.

"People called it the curious case of missing clouds."

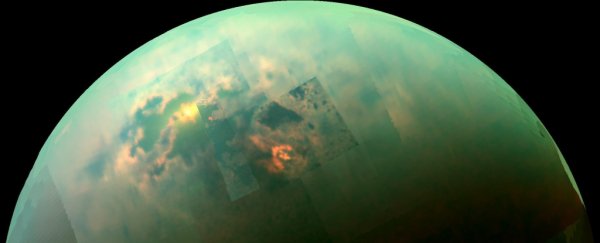

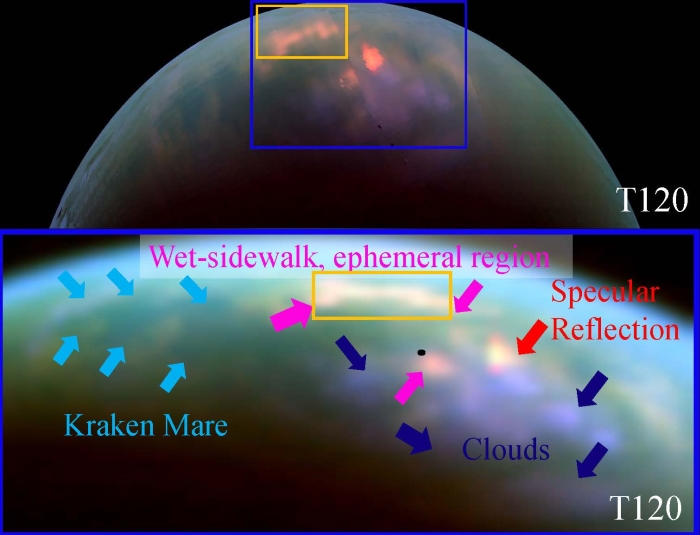

After carefully poring over Cassini's output, the team finally found what they were looking for in an image snapped on June 7, 2016. The picture came courtesy the spacecraft's Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) instrument, which can peer through Titan's thick, hazy atmosphere to the surface below.

(NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/University of Idaho)

(NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/University of Idaho)

Covering an area of 120,000 square kilometres (46,332 square miles) - about the size of Pennsylvania - was a strange shining region that had not appeared in either prior or subsequent images.

"Based on the overall brightness, spectral characteristics, and geologic context, we attribute this new feature to specular reflections from a rain‐wetted solid surface like those off of a sunlit wet sidewalk," the researchers wrote in their paper.

According to their analysis, the region is the result of methane rainfall onto a rough, pebble-like surface, likely followed by a period of evaporation. It's the first evidence of summer rain on Titan's northern hemisphere.

This rain was predicted, but scientists had expected to see it earlier in the season, based on theoretical models, especially since the northern hemisphere is where most of the moon's lakes and oceans are located.

Moreover, rainfall had been observed before on the southern hemisphere during summer; so scientists had expected rainfall to appear in the north years before the 2017 solstice.

The missing rain had therefore been something of a puzzle. Now that it's been found, Titan researchers have another piece of data to help figure out how the moon's climate works - although the delay itself remains as yet unexplained.

"We want our model predictions to match our observations. This rainfall detection proves Cassini's climate follows the theoretical climate models we know of," Dhingra said.

"Summer is happening. It was delayed, but it's happening. We will have to figure out what caused the delay, though."

Meanwhile, Dhingra is using the wet sidewalk effect to search Titan for more signs of rain that might have been missed over the years.

The paper has been published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.