A flesh-eating parasite has infected a person from the US in a rare and concerning event.

The case involved a woman in the state of Maryland, who had recently returned from Central America, where she was likely exposed to the New World screwworm fly (Cochliomyia hominivorax).

The patient has thankfully recovered, and the US Department of Health and Human Services has assured the public that the risk of further human spread is "very low".

That said, the parasite is worming its way northward, and could pose a big threat to US food security.

Related: Flesh-Eating Fly Invasion Could Cause Devastation Across America

Screwworm infections are caused by the larvae of screwworm flies, which look very similar to house flies. The insects typically lay their maggots in open wounds or around the navel or eye of warm-blooded animals, and the young then feast on the flesh, digging deeper with every bite.

Infectious disease specialist Daniel Griffin told CNN that the maggots turn "living tissue into Swiss cheese."

If untreated, infections can be fatal.

The most common victims of screwworms are cattle, horses, and pigs, but the parasite can also sometimes infect dogs, cats, and even humans. With the right treatment, survival is possible, but the worms act fast.

In as little as a week, screwworm larvae can kill a mature cow. A potential outbreak in Texas, the largest cattle-producing state in the US, could alone cost roughly $1.8 billion, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

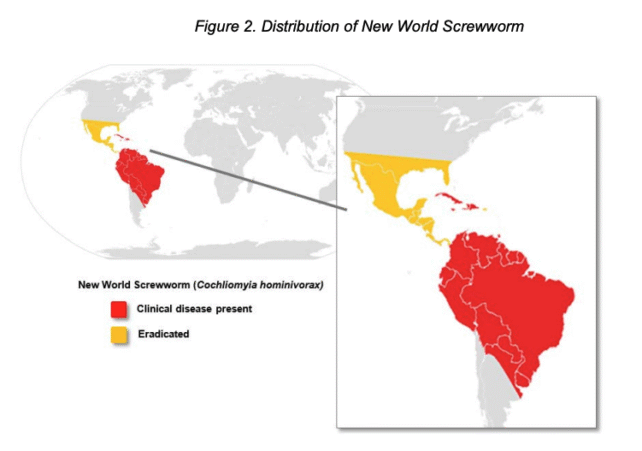

Screwworm flies are so destructive to livestock that in the 1950s, officials in the United States, Central America, and parts of the Caribbean tried to eradicate the pests. This involved releasing lab-bred sterile insects to interbreed with wild ones, and it largely worked.

The US last officially reported an endemic infection in 1982. While travelers returning to the country have sometimes brought back the worms, the New World infection has recently reemerged in places it was once largely eradicated, posing a risk to human health, food security, and the livelihoods of local ranchers.

Since the Central American outbreak began in early 2023, officials have reported hundreds of human cases in Nicaragua and Costa Rica, some of which required life-saving treatment.

"If those worms hadn't been removed, they would have destroyed their brain," said Ricardo Somarriba, director of Nicaragua's Institute for Agricultural Protection and Health.

The screwworm case in Maryland is an important reminder that nations must work together to control the spread of dangerous infections.