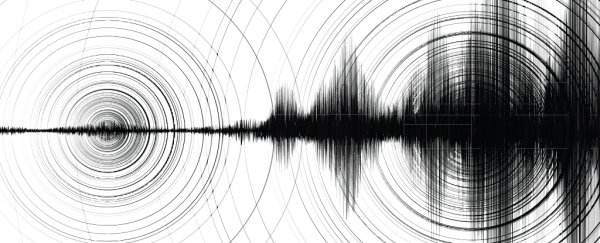

Aftershocks are a common feature of big earthquakes, but they usually occur relatively close to the tremor's epicenter.

For the first time, researchers have found evidence of earthquakes triggering seismic events on the other side of the globe, suggesting a ripple effect that could potentially be used to forecast catastrophes in the future.

Researchers at Oregon State University analysed nearly half a century of data on earthquakes and came to the startling conclusion that when big tremors strike, there's a good chance another quake will hit on the other side of the planet within the next few days.

"The test cases showed a clearly detectable increase over background rates," says agricultural scientist Robert O'Malley.

Most seismic events are caused by pieces of the crust grinding together as they're pushed and pulled by the gradual churn of the planet's molten guts.

Every now and then, when tension overcomes friction between those giant plates, there's a sudden release of energy that can often give rise to a cascade of smaller tremors along the boundary.

"Earthquakes are part of a cycle of tectonic stress buildup and release. As fault zones near the end of this seismic cycle, tipping points may be reached and triggering can occur," says O'Malley.

Those ripples of energy can give the surrounding surface a good shake, but there are also waves of pressure echoing down through the mantle. Not only have we long known about these, they're routinely used as giant sonar pings to study the planet's internal structure.

One particularly nasty quake that struck off the coast of the Indonesian island of Sumatra in 2004 made the entire globe ring like a bell, causing the whole crust to slowly jiggle up and down by as much as a centimeter (just under half an inch).

The planet-sized hum would have been too slow for people to feel, but it's not inconceivable that these reverberations just might have been big enough to tip distant pressure-points over the edge, setting off large earthquakes around the world.

Unfortunately, until now there's been no good evidence of a sizeable knock-on effect. Speculation is rife, but scientists have generally failed to see any confirming patterns.

Researchers in this new study wonder if they've been too constrained in their search.

This time they've widened the window of opportunity for distant powerful earthquakes over 5.0 on the Richter scale to strike to within three days of a major shake-up.

Even after excluding tremors that could be described as aftershocks, the team identified more earthquakes than would be expected within any given three-day period following seismic events that ring in over 6.0 on the scale.

The bigger the initial quake, the greater the chance of a follow-up. Interestingly, this jump is absent for the first 24 hours, which could help explain why other studies failed to identify a pattern.

What's more, most of these occurred within 30 degrees of the very opposite point on the other side of the globe.

The study made no attempt to shed light on possible explanations behind the increase in far distant earthquakes. For now, it's merely food for thought.

"The understanding of the mechanics of how one earthquake could initiate another while being widely separated in distance and time is still largely speculative," says O'Malley.

"But irrespective of the specific mechanics involved, evidence shows that triggering does take place, followed by a period of quiescence and recharge."

The findings contradict a 2011 study that looked at changes in earthquake frequency up to several months after large tremors.

The researchers suggest this new study may simply be more sensitive, though the contrast indicates there's plenty of research to be done before we can be confident there's a link.

Pinpointing exactly when and where catastrophic earthquakes will hit would have the potential to save a lot of lives, so any research that can help predict the likelihood of a tremor is bound to be useful.

This research was published in Nature Scientific Reports.