Explosive weapons training in the military has recently come under fire for its potential to cause brain injuries through blast waves alone, even when students and instructors are located a 'safe' distance from the blast itself.

A shocking new study has now found that exposure to repetitive, low-level blasts, like those that come from hand grenades, can be linked to a leaky gut. Because the permeability of the gut is controlled, in part, by neurons, experts suspect an association with decreased cognitive function.

According to neuroscientist Qingkun Liu and colleagues in the US, the symptoms are in line with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). Patients with TBI often experience abdominal pain, gastric distension, or constipation. They can also develop a leaky gut.

This leakiness coincides with a reduction in specific gut proteins, which help the walls of the intestine keep the riff-raff out. An increase in gut permeability can lead to bacteria leaking into circulation and possibly wreaking havoc on the body's systems – a feature of Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia.

"[S]ince blood has been generally considered a sterile environment that lacks microbes, studies on the human blood microbiome have received little recognition until recently," write Liu, who works at the James J Peter VA Medical Center in the Bronx, and his colleagues.

The team's study included 30 male participants, most of whom served as combat engineers and 18 of whom reported existing mild traumatic brain injury from direct blunt force trauma, though not from blasts.

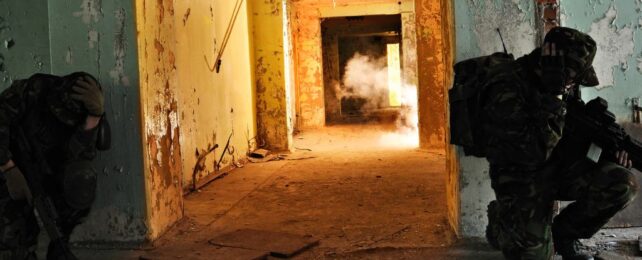

Shortly before, and around one hour after wall-breaching exercises, where participants stood 12 meters away from the blast, researchers took their blood. The next day, roughly 16 hours later, they took another sample.

Following the blast training, participants showed increased bacterial translocation in their blood circulation. Their protein biomarkers for gut leakiness were also out of whack.

An hour after the blast, the cohort reported symptoms like headaches, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, and taking longer to think, which gradually faded over 12 hours.

The results of the study, while purely observational, suggest that intestinal permeability may be linked to decreased cognitive functioning brought about by blast waves hitting the brain.

"To our knowledge, this is the first study that shows that exposures to blast in a military operational setting contributes to bacterial translocation and intestinal permeability along with associated cognitive symptoms, establishing the role of the gut–brain axis in blast-related sequelae," the authors conclude.

The findings come at a critical time in brain research. In March of 2024, The New York Times reporter Dave Philipps broke a story on the findings of a specialized lab at Boston University, which was investigating chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) among athletes, like football players.

Neuroscientists at the lab had found "moderately severe" damage in the brain of a deceased mass shooter and military veteran. The scarring and inflammation looked as though it was the result of repeated trauma. But not blunt force trauma. The trauma was characteristic of a shockwave.

Its signatures were similar to that of other military vets, who used weapons like shoulder-fired rockets that trigger blast waves. But this particular individual had never faced real-world combat before.

The only blasts he had ever been exposed to were at a military training camp he attended where soldiers were taught to use rifles, machine guns, grenades, and shoulder-fired rockets.

Phillips reports that over the years, the deceased mass shooter could have easily been exposed to more than 10,000 blasts, and while it's not clear if this was directly tied to his psychological symptoms or his criminal behavior, neuroscientists at Boston University say it's likely.

Clinically, the way blast brain damage manifests, it is often mistaken for post-traumatic stress disorder. Several years ago, US Army research teams investigated cases of blast instructors suffering from fatigue, headaches, memory issues, and confusion.

No action was taken to reduce their exposure. Even shoulder-fired rockets, which send shock waves scarily close to the brain, remain in wide use.

In response to recent research by the US Defense Department and an investigation by The New York Times connecting brain damage to artillery and rocket launchers, a bipartisan group of US Senators are demanding to know what the US military is doing to protect troops.

And it's not just high-level blasts in wartime that need to be considered.

Even when the blasts are kept at what is currently considered a 'safe' threshold by the US military, gathering evidence suggests they might put the firer and surrounding individuals at risk.

"If the right kind of wave hits brain tissue, the tissue just breaks — it literally gets torn apart," biomechanics expert Christian Franck told Times reporter Philipps in December of 2023. "We see that in the lab. But what kind of blast will do that in real life? It's complex… There is a lot we don't know."

While the current study is small and lacks a control group, it joins a wave of new research that suggests blunt force trauma isn't the only way to damage the brain, and that low-level blasts are also a problem.

To protect instructors, students, and veterans in the military, further research is desperately needed.

The study was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.