For the first time, researchers have discovered a way to convert the white fat cells that sit in unsightly, energy-storing clumps around our bodies into energy-burning brown fat. If they can figure out how to apply this method to medical treatments, obese patients and those with metabolic issues could be given the ability to increase their energy expenditure without having to adjust their exercise routine.

The team, from the University of Texas in the US, had previously discovered that we all have little deposits of 'good' brown fat, and when these are activated, they can increase our metabolic rate and also lower our blood glucose levels. They've now figured out how 'bad' white fat can be prompted to perform similar roles, but only when the body is subjected to severe, adrenaline-releasing stress - such as burning or freezing - over a long period of time. While this isn't exactly ideal, by understanding the mechanisms at play here, scientists could one day develop treatments that mimic the effects of prolonged stress to get the same results.

The team worked with 72 patients who had severe burns over approximately 50 percent of their bodies, and 19 healthy people acted as controls. They periodically took white fat samples from the burned patients, and measured the metabolism at work inside them, the composition of the fat, and the patients' own metabolisms, before comparing these with the control group.

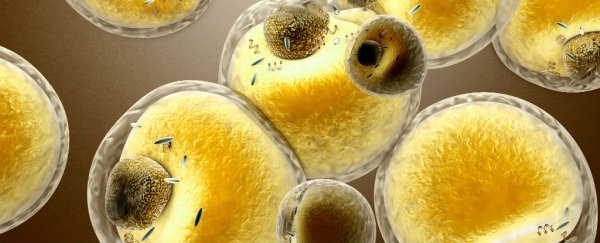

The idea was to figure out if the white fat samples were different between the two groups, perhaps because the samples from the burned patients were changing to resemble brown fat cells. It's fairly easy to tell the difference between the two - they're genetically distinct, have different physical structures, and perform different functions.

For example, brown fat cells are smaller than white ones, but pack a higher number of mitochondria into their compact frames. These mitochondria work hard to produce a specific type of protein, called uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), and according to the university press release, this protein is activated by adrenaline.

When a person is severely burned, the body continues to be stressed for several weeks after the actual injury, and this causes a constant release of extra adrenaline. This extra adrenaline is activated by the UCP1, which then prompts the mitochondria to increase the rate at which it burns calories. And the best part is it does this without producing any chemical energy - it only uses heat.

Publishing in the journal Cell Metabolism, the researchers say they saw a gradual change in the white fat cells of the burned patients. Structurally and functionally, they began to resemble brown fat cells, which suggests that they were getting progressively 'browner' over the course of the prolonged burn response.

"Our study provides proof of concept that browning of white fat is possible in humans," lead author Labros Sidossis said. "The next step is to identify the mechanisms underpinning this effect and then to develop drugs that mimic the burn-induced effect."

Scientists are already working towards that goal, and Alice Park reports for TIME that around 40 agents in animal models are being investigated based on their potential to convert white fat to more efficient brown fat work. "Now that there's evidence that the process does occur in people - albeit under extreme conditions - studying those substances further to see if they can accomplish the same transformation of white fat, without the stress, seems worthwhile."