Researchers might have finally figured out why the world's largest shark, megalodon (Carcharocles megalodon), went extinct 2.6 million years ago – and it's all to do with its favourite meal.

Based on new fossil analysis, the team says the mighty, 16-metre-long (52-foot) sharks likely died off after their favourite prey item – dwarf whales – disappeared from the warming planet, giving way to the larger whales we know today.

"The disappearance of the last giant-toothed shark could have been triggered by the decline and fall of several dynasties of small to medium-sized baleen whales in favour of modern, gigantic baleen whales," team leader Alberto Collareta from the University of Pisa, Italy, told Richard Gray over at New Scientist.

If you're unfamiliar, megalodon was a gigantic, prehistoric shark that would put the great white shark in Jaws to shame. With a 3-metre-wide (9.8-foot) jaw that could crush pretty much anything in front of it, these huge sharks were a true force to be reckoned with.

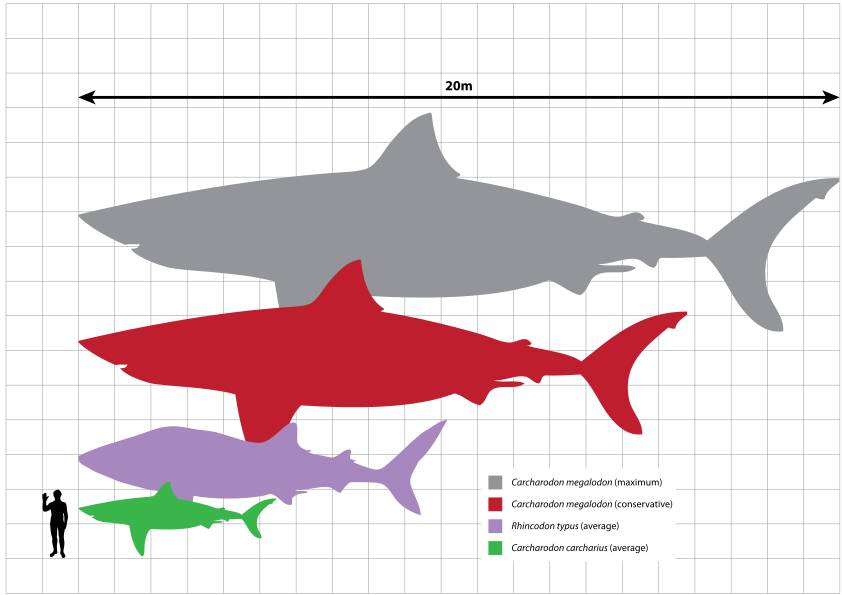

Here's what they look like compared to other sharks today:

Rhincodon typus (purple) is the whale shark, and Carcharodon carcharias (green) is the great white shark. Grey is the maximum size estimate for megalodon, and red is the conservative size estimate:

It's believed that megalodons roamed the oceans for around 20 million years, before they suddenly went extinct roughly 2.6 million years ago. The reason for this sudden decline has been much-debated, but now Collareta and his team might have figured it out.

Based on the analysis of teeth marks left on 7-million-year-old marine mammal fossils, the team has identified the shark's most favourite prey item: the dwarf whale, along with some seal appetisers.

"Among those carrying marks left by megalodon teeth were the jawbone of a diminutive, extinct species of baleen whale called Piscobalaena nana and an early type of seal called Piscophoca pacifica," Gray reports for New Scientist.

"Both animals grew to less than 5 metres in length – under a third the size of megalodon."

While the animal became accustomed to hunting these particular prey, the team says that a warming climate all those years ago killed off many smaller whales that lived along the world's coastlines – including the dwarf whale.

Not only did that mean less dwarf whales for megalodons to hunt, but as Earth's poles melted and gave way to bountiful ocean ecosystems, larger creatures like today's sperm and blue whales adapted quickly to these polar, cold waters, becoming the majestically huge, open-water-loving beasts we know now.

The researchers say this shift in whale populations did two things to megalodon: it forced it to start hunting larger whales, which were often much too big to take down, and kept them in their coastal habitats, unable to survive the chill of the poles where other large marine creatures found a haven of food.

This created a double whammy of hunger for megalodon that could have led to its demise.

Some have claimed that the sharks might have successfully eaten larger prey from time to time, though it remains unclear if they were able to take down the larger prey themselves, or were simply scavenging their carcasses.

More work will need to be done to fully understand all of the aspects of the megalodon collapse, but now we finally have a clue as to what could have taken down the world's biggest shark – plain old hunger.

The team's work was published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.