A condition that compels people to move their legs could indicate they have a greater chance of developing Parkinson's disease. A new study also suggests this risk decreases for those prescribed certain treatments for their 'restless legs'.

Also known as Willis-Ekbom disease, restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a neurological disease that creates an uncomfortable sensation in the lower limbs, driving those with the condition to change position frequently.

This is far from the first time researchers have investigated potential links between RLS and Parkinson's. Both conditions are defined by difficulties in controlling movement, and each is treated with drugs that activate the dopaminergic pathway by mimicking the neurotransmitter dopamine.

It's been speculated that RLS may even be an early clinical feature of Parkinson's, potentially signaling the dopaminergic pathway faltering. However, previous studies have been limited or unclear about the nature of any association.

Here, researchers in South Korea analyzed the health records of 9,919 people with RLS, matching them by age, sex, and other variables with individuals without the condition. These two groups were then followed for a period of up to 15 years.

Related: Protein That Pokes Holes in Cells Could Explain Parkinson's Decline

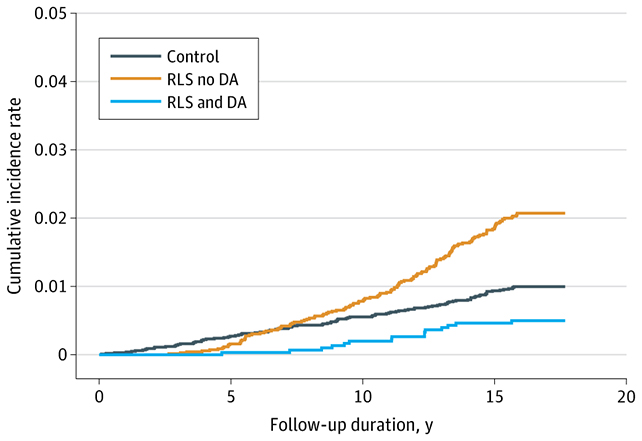

There was a significantly higher chance of those in the RLS group developing Parkinson's disease compared to the control group: a 1.6 percent chance compared to a 1 percent chance.

"In this cohort study, RLS was associated with an increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease," the researchers write in their published paper.

"Furthermore, patients with RLS who were not treated with dopamine agonists tended to be at increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease, whereas those who were treated with dopamine agonists tended to be at decreased risk compared with the control group."

That additional finding suggests any link between RLS and Parkinson's disease may not be related to a breakdown in the dopaminergic pathway. For those people with RLS who took drugs that activated the pathway, the association with Parkinson's disease went away.

The researchers suggest there may be a complex interplay of factors affecting both RLS and Parkinson's, which might include poor sleep health and iron deficiency.

Not everyone who has RLS gets Parkinson's disease, which isn't always preceded by RLS. They do appear to be connected in ways that future research may be able to tease out, however.

"It is possible that the pathophysiological bridge between RLS and Parkinson's disease may involve alternative mechanisms other than the dopaminergic pathway," write the researchers.

"Based on these findings, it may be more reasonable to interpret RLS as a potential risk factor for Parkinson's disease rather than an early manifestation."

The statistical margins weren't large: the difference in the average time of a Parkinson's diagnosis between the RLS group and the control group was only a few weeks, for example. However, these differences can soon add up across the millions of people living with Parkinson's.

It's fair to say there's still a lot we don't know about both RLS and Parkinson's disease, but associations like this – and especially the role of dopamine agonists on risk – can help shed light on how these conditions get started, and how more effective treatments might be developed.

"Clarifying this association and the role of the dopaminergic pathway may improve understanding of the pathophysiology between these two diseases," write the researchers.

The research has been published in JAMA Network Open.