River piracy, also known as stream capture, happens when melting glaciers divert the path of a river. Due to our warming planet, a major Alaskan river is under threat of being redirected in this way – stealing an essential source of water away from the ecosystems and people that rely on it.

The threatened waterway is the Alsek River, flowing down from the St Elias mountain range in Canada, to Dry Bay in Alaska. Before it reaches the Pacific Ocean, it passes through Alsek Lake.

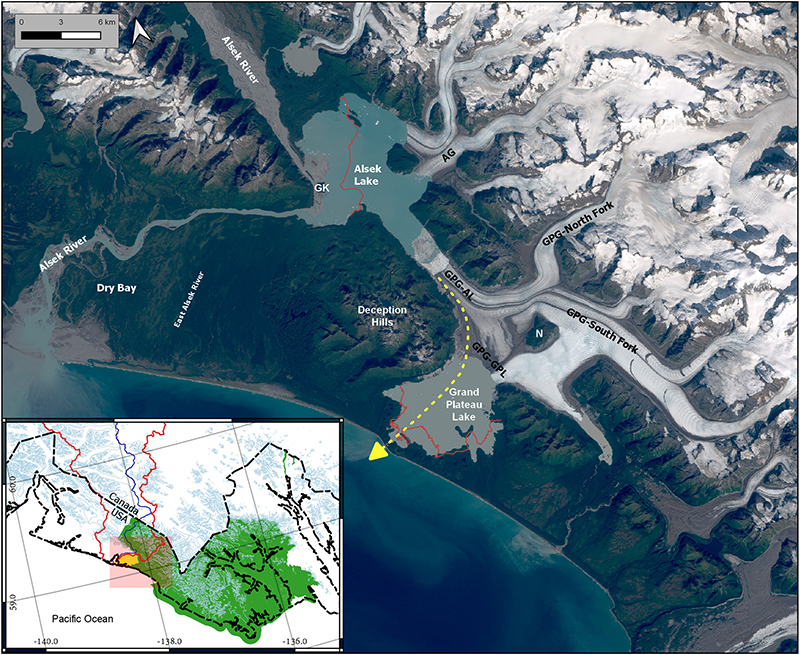

Alsek Lake is separated from another body of water, the Grand Plateau Lake, by the Grand Plateau Glacier – and as that glacier melts away over the next couple of decades, these two lakes are almost certain to join up, redirecting the river through Grand Plateau Lake and away from Dry Bay.

How the course of the Alsek River is likely to change. (Loso et al., Geomorphology, 2021)

How the course of the Alsek River is likely to change. (Loso et al., Geomorphology, 2021)

"Radar data allowed us to demonstrate that the glacier's depth is such that when the ice is gone, there will be nothing to prevent the two lakes from connecting," says geologist Michael Loso from the US National Park Service.

The rate of melting on the Grand Plateau Glacier is increasing, with the glacier at times receding by more than 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) per year in recent years. Radar soundings show that the glacier goes deeper than both lakes on either side, so no barriers will remain.

Based on the researchers' predictions, the mouth of the Alsek River could end up almost 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) to the south east within the next 30 years – and inside an area of designated wilderness, Glacier Bay National Park.

That has an impact on the surrounding wildlife, including the fish in the Alsek River and the community that has built up around Dry Bay. Without the water supply from further up, the researchers expect the lower, abandoned part of the Alsek River to become sluggish and choked with vegetation.

"It's going to be complicated," Loso told the The Guardian. "It's going to involve a combination of people who use that area changing their expectations and their plans and their patterns of behavior to accommodate the river not being there."

Dry Bay is home to almost 60 companies with commercial use authorizations, a salmon fishery, 19 camps for commercial fishers, and three commercial fishing/hunting lodges. It also attracts around 800 rafters a year, who get back home from one of the eight airstrips near Dry Bay.

All of these operations will be under threat once the river shifts: there are no air strips around Grand Plateau Lake, for example, and they can't be built in areas of National Park Wilderness.

In terms of the bigger picture, Loso and his colleagues think that river piracy events like this are likely to get more frequent as climate change progresses.

While Dry Bay is a relatively remote outpost, this sort of river piracy needs further investigation, the researchers argue. It often goes unnoticed in remote regions, but the impacts can potentially be very significant indeed – and based on earlier studies, it's happening faster than ever too.

By better understanding when and where this is likely to happen – not easy, considering how complex the prediction of glacier melting and calving can be – communities can be better prepared for the threat of rivers disappearing for pastures new.

"There is hope that this dynamic event will draw attention to the region and the challenges that climate change is presenting and, through that, help inspire people to visit and come to understand the scale of the change that is occurring," says local raft expeditioner Joel Hibbard, who wasn't involved with the study.

The research has been published in Geomorphology.