Humans are yet to set foot on Mars, but over time, Mars has come to the humans. Chunks of Martian rock ejected from their homeworld by processes such as violent impacts have wended their way through the Solar System to end up – smack! – crashing into Earth.

As we collect these samples of our neighboring planet, a curious pattern has emerged. Most of the samples seem to be rocks that formed on the red planet fairly recently; a peculiarity, given most of the Martian surface is so old.

It is possible the measures of age are largely wrong. Different dating techniques have returned different results, which means scientists aren't fully confident in estimates of when these rocks formed on Mars.

A team of scientists from the US and UK has now found a way to resolve this problem. And, to their surprise, many of these rocks are indeed quite young – just a few hundred million years old, in fact. This information could provide clues about how long the meteorites took to get here, as well as geological processes on Mars.

"We know from certain chemical characteristics that these meteorites are definitely from Mars," says volcanologist Ben Cohen of the University of Glasgow, who led the research.

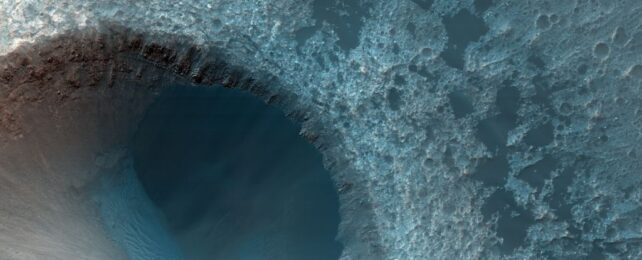

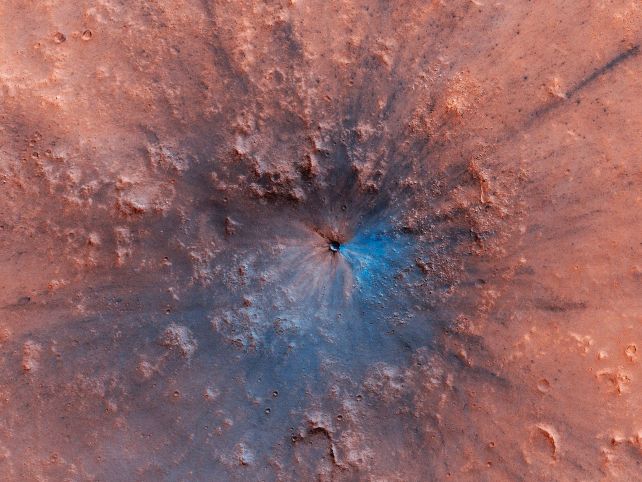

"They've been blasted off the red planet by massive impact events, forming large craters. But there are tens of thousands of impact craters on Mars, so we don't know exactly where on the planet the meteorites are from. One of the best clues you can use to determine their source crater is the samples' age."

There are around 360 or so meteorite samples found on Earth that have been identified as having a Martian origin. Some 302 of these at time of writing – so, most of them – are classed as shergottite, a type of metal-rich Mars rock forged in the heat of volcanic activity.

Based on how heavily cratered Mars' surface is, scientists have estimated that surface to be pretty old. If the surface was younger, refreshed by volcanic activity, many of the craters would be erased by volcanic flows. So any rocks that get ejected from the Martian surface should also be old.

Not only are dating techniques on shergottite here on Earth complicated by their makeup, but what little we have been able to glean from them has suggested many are less than 200 million years old. This has led to what is known as the shergottite age paradox, and it's been bugging scientists for decades.

Explanations for this surprisingly young possibility ranged from a single point of origin for all the younger shergottite, to the idea that the impact event could have heated and smushed the rock to such a degree that its age was sort of reset. But these theories didn't stack up to the evidence – the rocks themselves.

The method used to determine the age of shergottite is known as argon-argon dating, which is based on the decay of radioactive potassium into argon. Since this decay rate produces a known ratio of argon isotopes, scientists can look at that ratio to determine how long the radioactive decay has been taking place, and thus date the rock sample.

The problem is that, here on Earth, we can easily take into account different sources of argon that may make its way into a sample. For shergottite, which started on a whole other planet and spent goodness knows how long in space, this is more complicated. There are five potential sources of argon for shergottite, compared to just three for Earth rocks.

To compensate for this, Cohen and his colleagues developed a method to correct for argon contamination from Earth and space. "Once we did that, the argon-argon ages came out as being young and matched perfectly with other methods, like Uranium-Lead," he explains.

They dated seven samples of shergottite, returning ages ranging between 161 million and 540 million years ago. The researchers say that the reason for this might be the frequent bombardment of Mars has broken up the older surface, exposing the younger rock beneath, that has been replenished by volcanic activity. Eventually, it becomes more likely that that younger rock is excavated and ejected.

Martian volcanic activity may still be ongoing today, and Mars is under constant bombardment. Scientists have estimated some 200 impacts every year create craters more than 4 meters in diameter. So it's probably not surprising that younger rocks occasionally get flung towards Earth, in a roundabout Solar-System-y sort of way.

The research has been published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.