A new deep dive into humanity's history of romantic kissing has revealed that locking lips has a more complex story than some researchers have proposed.

Though smooching one's love interest might not be a human-only pastime, not all cultures do it, leading to speculation over the behavior emerging in select localities before spreading like the latest dance craze.

According to Assyriologist Troels Pank Arbøll of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and biologist Sophie Lund Rasmussen of the University of Oxford in the UK, suggestions that kissing popped up in some places like India before spreading the fashion elsewhere aren't supported by the larger pool of evidence.

It has been generally accepted for some time that the earliest written record of romantic kissing is from the Hindu Vedic Sanskrit texts, dated to around 3,500 years ago. The late anthropologist Vaughn Bryant used this depiction to suggest Alexander the Great's generals may have brought the fad back with them after their conquest of Punjab in 326 BCE.

Yet even if that were the case, Arbøll and Rasmussen point out that the earliest known record of the romantic expression dates to around 4,500 years ago in Egypt and Mesopotamia, at least 1,000 years prior to its appearance in Vedic Sanskrit scriptures.

Similarly, a paper published last year speculated the rise of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), the pathogen responsible for cold sores, might help trace the cultural transmission of kissing some 5,000 years ago.

"Evidence indicates that kissing was a common practice in ancient times, potentially representing a constant influence on the spread of orally transmitted microbes, such as HSV-1," Arbøll and Rasmussen write in their paper.

"It therefore seems unlikely that kissing would have arisen as an immediate behavioral adaptation in other contemporary societies, which inadvertently accelerated disease transmission."

The history of romantic kissing is tricky to unravel, and experts don't agree on whether it's learned or instinctive. We know that kissing is certainly not unique to humans; bonobos and chimpanzees kiss each other. On the other hand, previous research has found that romantic kissing is not universal among humans. That same research also found that the more socially complex a culture, the more romantic kissing its people engage in.

While adults might kiss their children, the act of adults kissing one another out of pure enjoyment is often harder to decipher in the historic record. According to Arbøll and Rasmussen, references to romantic kissing can be found in the earliest Sumerian texts from 2500 BCE onwards, described in relation to erotic acts, with a particular focus on the lips.

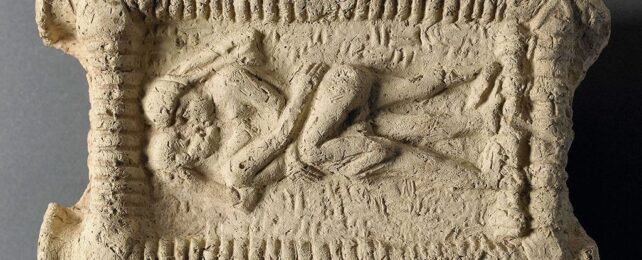

"In ancient Mesopotamia, which is the name for the early human cultures that existed between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in present-day Iraq and Syria, people wrote in cuneiform script on clay tablets. Many thousands of these clay tablets have survived to this day, and they contain clear examples that kissing was considered a part of romantic intimacy in ancient times, just as kissing could be part of friendships and family members' relations," Arbøll says.

"Therefore, kissing should not be regarded as a custom that originated exclusively in any single region and spread from there but rather appears to have been practiced in multiple ancient cultures over several millennia."

It's possible that kissing has been around much longer, too. A 2017 paper delving into the genomic data of the oral bacteria found in the mouths of Neanderthals found that there was a transfer of some oral microbes between humans and Neanderthals around 126,000 years ago. That's far from hard evidence of sexy smooching, but it's not nothing, either.

Prehistoric sculptures from 11,000 years ago in the Middle East and the Neolithic in Malta up to 5,000 years ago also seem to depict people kissing as they engage in erotic acts.

That's not to suggest that kissing hasn't, historically, played a role in the spread of disease. It probably did. Arbøll and Rasmussen note that medical texts from ancient Mesopotamia detail a disease that sounds very similar to HSV-1, which today affects some 3.7 billion people worldwide.

"It is … interesting to note some similarities between the disease known as buʾshanu in ancient medical texts from Mesopotamia and the symptoms caused by herpes simplex infections," he says. "The bu'shanu disease was located primarily in or around the mouth and throat, and symptoms included vesicles in or around the mouth, which is one of the dominant signs of herpes infection."

Yet the authors stress differences between the interpretation of illness in the past and how we view it today mean researchers need to be cautious in using ancient medical texts to trace other cultural practices.

This combined evidence makes it difficult to interpret kissing as having a significant role in the rise of any one particular disease or strain of disease, based on the records we currently have available. That's not to say kissing has never played a role… but that investigating that role should be a collaborative effort that includes a variety of experts.

"The debate about kissing as a vector of disease transmission," the researchers write, "illustrates the benefits of an interdisciplinary approach to produce a holistic representation of historical disease transmission through social interactions."

Their paper has been published in Science.