After decades of decline, scarlet fever is once again on the rise in the UK and other places around the world, and doctors are scrambling to figure out why.

Beginning in 2014, the infection started to steadily rise, and in 2016, over 19,000 cases from 620 outbreaks were reported, mostly in schools and nurseries. This represents a seven-fold increase since 2011.

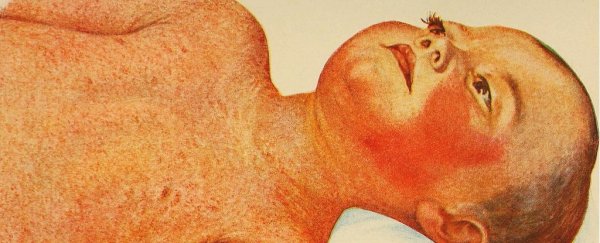

Scarlet fever is a bacterial infection caused by a Group A Streptococcus. It's characterised by a sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, "strawberry tongue", and a rash.

It may not sound terrible based on those symptoms, but it was responsible for 36,000 registered deaths in the first decade of the 20th century in England and Wales, and was a leading cause of child mortality.

There's no vaccine for scarlet fever. Once contracted, it's treated quite easily with a course of antibiotics, which - at least partially - contributed to the disease's decline in developed countries after about 1945.

The most obvious reason for a resurgence in a bacterial infection would be a new strain of the disease that spreads more easily and is possibly antibiotic-resistant - but molecular genetic testing has ruled this out.

Instead, tests showed a range of already established strains of the bacteria, leaving researchers still looking for a possible cause.

Meanwhile, the 2016 statistics put incidence at 33.2 cases per 100,000 people, with 1 in 40 cases being admitted to hospital (although around half of those get discharged the same day).

Overall, there were 19,206 reported cases - the highest number since 1967, and an astonishing rise from 2013, when there were just 4,643 cases reported.

Doctors are urging the public to be alert to the symptoms while they seek solutions.

"Whilst current rates are nowhere near those seen in the early 1900s, the magnitude of the recent upsurge is greater than any documented in the last century," said epidemiologist Theresa Lamagni of Public Health England, who led the study.

"Whilst notifications so far for 2017 suggest a slight decrease in numbers, we continue to monitor the situation carefully. Guidance on management of outbreaks in schools and nurseries has just been updated and research continues to further investigate the rise.

"We encourage parents to be aware of the symptoms of scarlet fever and to contact their GP if they think their child might have it."

Recent outbreaks have also occurred in China, Vietnam, South Korea and Hong Kong, but testing revealed only very minor genetic elements in common.

There is, the researchers said, no clear link between the Asian outbreaks and the UK outbreaks - but that doesn't mean a link can be ruled out yet.

"Hypotheses that have been proposed include acquisition of scarlet fever-causing genes into the S pyogenes population, changes in immune status in the human population, environmental change, and an as yet unknown and potentially novel co-infective agent that predisposes the host to disease," wrote microbiologists Mark Walker and Stephan Brouwer from the University of Queensland in a comment on the article.

"Further research needs to be done to better understand the causes of scarlet fever resurgence. Scarlet fever epidemics have yet to abate in the UK and northeast Asia. Thus, heightened global surveillance for the dissemination of scarlet fever is warranted."

The research has been published in the journal The Lancet.