Researchers in China have opened a new window into the deep past by blasting dinosaur eggs with a laser, dating them directly for the first time.

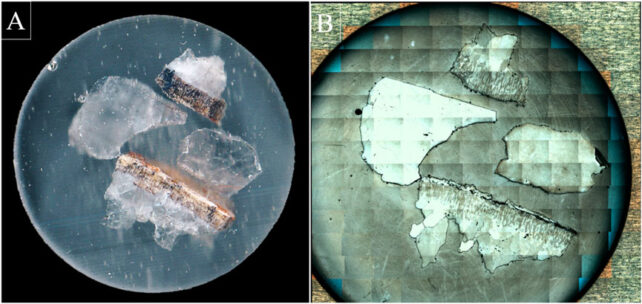

A micro-laser was used to vaporize small portions of an eggshell, which released a cloud of radioactive uranium atoms. Since uranium decays into lead at a known, steady rate, researchers could ascertain the eggs' age by measuring the ratio of uranium to lead in the sample.

This common technique, called U-Pb dating, is like looking at a fossil's hidden atomic clock, allowing the researchers to tease out a more precise age coinciding with the Upper Cretaceous around 85 million years ago.

Related: Stunningly Complete Dome-Headed Dinosaur Emerges From The Sands of Mongolia

Previously, scientists focused on dating the materials surrounding fossilized dinosaur eggs, relying on volcanic rocks, ash, or minerals like the famously immortal zircon crystals. However, such indirect dating methods introduce uncertainties.

First, these materials may have been deposited long before or after the eggs were laid. Secondly, the materials around the eggs must contain sufficient radioactive elements within them to allow proper dating, which is why volcanic rocks are invaluable.

Being able to directly and precisely date the eggs (despite the sediments around them not being particularly radioactive) offers a unique view of the past.

The Upper Cretaceous spanned from around 100 million years ago to around 66 million years ago, to that fateful day when an asteroid ended the dinosaurs' reptilian reign.

Studying this timeline is essential. Despite the pop-media misnomer, the Cretaceous Period is the real Jurassic Park. It's a period of extreme dinosaur diversity and abundance, and while it is very well-studied in marine records, terrestrial records remain spotty.

Geographically, the clutch of 28 eggs hails from Qinglongshan in central China, a site so egg-rich it's been turned into a gigantic dino-egg museum. The area holds over 3,000 partially exposed, generally intact dinosaur eggs. They're also remarkably abundant and varied, nestled within different types of rocks and displaying diverse shell structures and nesting styles.

Most of Qinglongshan's eggs had been laid by a still-mysterious species known as Placoolithus tumiaolingensis, though it's uncertain what species laid the eggs dated in this study.

China's embarrassment of eggs offers scientists a vital land-based record of the late Cretaceous, which was also a time of dynamic climate change. This period saw increased volcanic activity, a depletion of oxygen in the oceans, and significant global cooling.

This cooling seems to have reduced dinosaurian diversity and may have affected the number of eggs laid by certain species at Qinglongshang and elsewhere. The eggs themselves may have changed; those found at Qinglongshang are markedly porous, so was this an adaptation to the cooling Cretaceous?

More precise dating strategies can unearth these stories, hidden for tens of millions of years, to reveal paleo-environments, dinosaur migrations, and prehistoric climatic fluctuations.

"Our achievement holds significant implications for research on dinosaur evolution and extinction, as well as environmental changes on Earth during the Late Cretaceous," explains Bi Zhao, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Hubei Institute of Geosciences.

"Such findings can transform fossils into compelling narratives about Earth's history."

And truly, what's more compelling than the evolution and extinction of prehistory's most awe-inspiring creatures, and the long-lost worlds that existed when our own Earth was an alien planet?

This research is published in Frontiers in Earth Science.