Scientists have developed a brand new, clear coating that can be applied to any standard window to turn it into an effective solar panel – while still keeping the window largely transparent.

It's the work of a team from Nanjing University in China, and the researchers have already developed a small working prototype. Scale that up across all the available windows in the world, and we could be talking about terawatts of green energy.

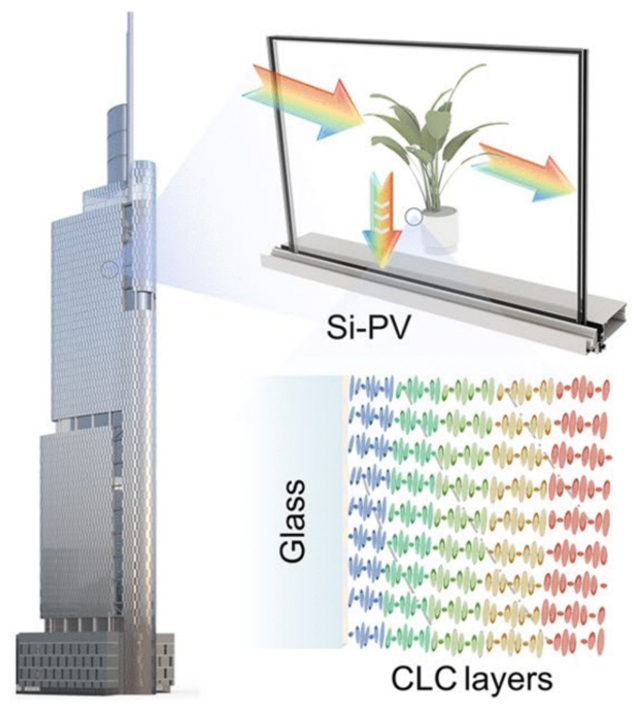

Technically known as a "colorless and unidirectional diffractive-type solar concentrator" (CUSC), the coating directs some sunlight photons to the sides of the window panel where mounted photovoltaic cells convert them to electricity, while other light passes through.

Related: Floating Solar Panels at The Equator Could Provide Virtually Unlimited Energy

"The CUSC design is a step forward in integrating solar technology into the built environment without sacrificing aesthetics," says optical engineer Wei Hu. "It represents a practical and scalable strategy for carbon reduction and energy self-sufficiency."

This new coating beats existing options in terms of transparency, scalability, and efficiency, according to the researchers. The coating still lets 64.2 percent of visible light through, and maintains 91.3 percent color accuracy.

The material is made from cholesteric liquid crystals (CLCs), which have properties that enable the necessary interactions with light as it passes through. By stacking different layers of CLCs, the coating is able to cover the full spectrum of light.

Crucially, only one polarization of light – so a single one of the multiple ways that light is moving as a wave – is trapped and siphoned off for converting into energy. That enables the window to carry on functioning as a window.

"By engineering the structure of cholesteric liquid crystal films, we create a system that selectively diffracts circularly polarized light, guiding it into the glass waveguide at steep angles," says optical engineer Dewei Zhang.

In tests using green laser light – the color that human eyes are most sensitive to – 38.1 percent of the available energy was captured and converted, which is a high potential maximum for the technology. In tests using more realistic conditions and the full light spectrum, the overall efficiency was 18.1 percent.

The researchers have already been able to develop a 1-inch prototype using the coating, which collects enough energy to power a small fan. Scale that up to a full-size window, and a substantial amount of electricity could potentially be generated.

As the coating can be applied to normal windows, without too much in the way of modification, the team is hopeful that this can be made commercially viable – though there's still a lot of work to do before that happens.

The researchers say more can be done to improve the stability and the manufacturing of the coating, and the power conversion efficiency needs to be improved too – the total amount of incoming solar energy that actually makes it into usable electricity. Right now, that figure stands at a relatively low 3.7 percent.

"To scale up production, several improvements in materials and procedures need to be considered," write the researchers in their published paper.

The research has been published in PhotoniX.