Researchers at the University of Bristol in the UK have taken a major step forward in synthetic biology by designing a system that performs several key functions of a living cell, including generating energy and expressing genes.

Their artificially constructed cell even transformed from a sphere shape to a more natural amoeba-like shape over the first 48 hours of 'life', indicating that the proto-cytoskeletal filaments were working (or, as the researchers put it, were "structurally dynamic over extended time scales").

Building something that comes close to what we might think of as alive is no walk in the park, not least thanks to the fact even the simplest of organisms rely on countless biochemical operations involving mind-bendingly complex machinery to grow and replicate.

Scientists have previously focused on getting artificial cells to perform a single function, such as gene expression, enzyme catalysis, or ribozyme activity.

If scientists crack the secret to custom building and programming artificial cells capable of mimicking life more closely, it could create a wealth of possibilities in everything from manufacturing to medicine.

While some engineering efforts focus on redesigning the blueprints themselves, others are investigating ways to reduce existing cells to scraps that can then be reconstructed into something relatively novel.

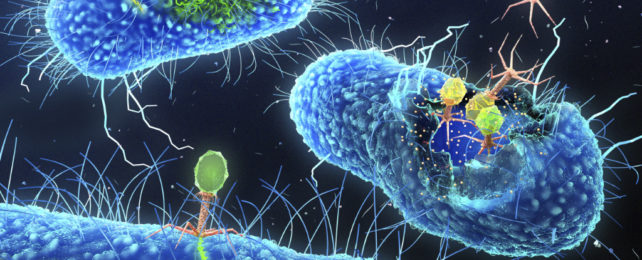

To perform this latest bottom-up bioengineering feat, researchers used two bacterial colonies – Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa – for parts.

These two bacteria were mixed with empty microdroplets in a viscous liquid. One population was captured inside the droplets and the other was trapped at the droplet surface.

The scientists then burst open the bacteria membranes by bathing the colonies in lysozyme (an enzyme) and melittin (a polypeptide which comes from honeybee venom).

The bacteria spilled their contents, which were captured by the droplets to create membrane-coated protocells.

The scientists then demonstrated that the cells were capable of complex processing, such as the production of the energy storage molecule ATP through glycolysis, and the transcription and translation of genes.

"Our living-material assembly approach provides an opportunity for the bottom-up construction of symbiotic living/synthetic cell constructs, says first author, chemist Can Xu.

"For example, using engineered bacteria it should be possible to fabricate complex modules for development in diagnostic and therapeutic areas of synthetic biology as well as in biomanufacturing and biotechnology in general."

In the future, this kind of synthetic cell technology could be used to improve ethanol production for biofuels and food processing.

Combined with knowledge based on advanced models of basic biology, we could mix-and-match some structures while redesigning others completely to engineer whole new systems.

Artificial cells could be programmed to photosynthesize like purple bacteria, or generate energy from chemicals just like sulfate-reducing bacteria do.

"We expect that the methodology will be responsive to high levels of programmability," the researchers say.

This paper was published in Nature.