Those 'crow's feet' at the corners of your eyes really do deserve to be called laughter lines, according to a recent study by researchers from Binghamton University in New York.

Using skin samples from people aged 16 to 91, the team confirmed the repeated stretching and releasing of skin in one direction strains the aged tissue in a way that leads to wrinkles in a similar fashion to the wearing of creases into your favorite pair of denim jeans.

"This is no longer just a theory," says biomedical engineer Guy German. "We now have hard experimental evidence showing the physical mechanism behind aging."

Related: Sleep Wrinkles Are a Real Thing, And It's All About How You Sleep

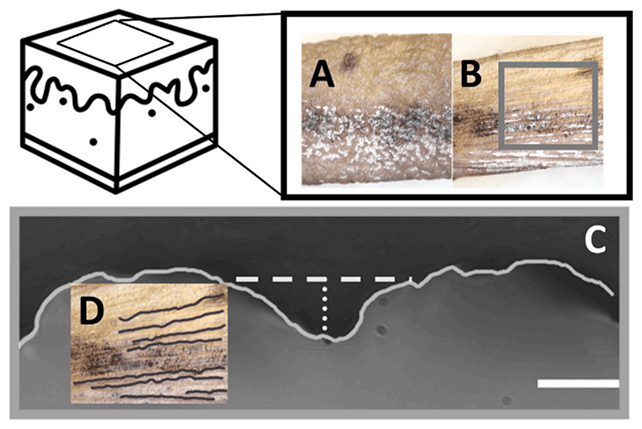

While previous studies have explored the mechanics of dermal stress and degradation, this investigation is the first to physically test real skin samples with an instrument called a low-force tensometer and observe the resulting changes under a microscope.

The stress applied by the tensometer was intended to mimic the wear and tear of everyday life. The researchers found that the skin contraction movements made in response to the stretches got bigger with age, causing buckling and wrinkling.

Our skin is also in a semi-stretched state by default, the researchers found, and those forces also change as we get towards later life. The outer layer (stratum corneum) gradually gets stiffer, while the underlying layer gets softer as the density of its collagen scaffolding decreases.

Over time, skin loses volume by pushing out fluid, the team's experiments showed, exacerbating the effects of wrinkles. This poroelastic quality of the skin is significant, and hasn't been recorded before.

"If you stretch Silly Putty, for instance, it stretches horizontally, but it also shrinks in the other direction – it gets thinner," says German. "That's what skin does as well."

"As you get older, that contraction gets bigger. And if your skin is contracted too much, it buckles. That's how wrinkles form."

The research is about more than just knowing where wrinkles come from. By understanding the characteristics of our skin, and how they change over time, we can better understand (and treat) a variety of different skin diseases.

It's not just the outer skin that the researchers are interested in, either: they suggest that their work could have implications for modeling other tissues. These techniques could be applied to wrinkles in the brain as well, for example.

The findings here could also be important when it comes to caring for the skin – and assessing just how effective various anti-aging skin products actually are (especially as there are so many of them vying for our attention).

In addition, the researchers make the link between the effects of chronological aging on the skin, and the damaging effects of exposure to the Sun's ultraviolet radiation – something that sunscreen can help prevent.

"If you spend your life working outside, you're more likely to have more aged and wrinkled skin than those who are office workers, for example," says German.

The research has been published in the Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials.