Scientists keep peeling back new layers of life on our planet like a seemingly endless onion.

Most recently, aquanauts on board a vessel from the Schmidt Ocean Institute used an underwater robot to turn over slabs of volcanic crust in the deep, dark Pacific.

Underneath the seafloor of this well-studied site, the international team of researchers found veins of subsurface fluids swimming with life that has never been seen before.

It's a whole new world we didn't know existed.

"On land we have long known of animals living in cavities underground, and in the ocean of animals living in sand and mud, but for the first time, scientists have looked for animals beneath hydrothermal vents," says the institute's executive director, Jyotika Virmani.

"This truly remarkable discovery of a new ecosystem, hidden beneath another ecosystem, provides fresh evidence that life exists in incredible places."

Scientists only discovered hydrothermal vents, which gush hot, mineral-rich fluids in the deep ocean, in the 1970s. Despite the darkness of these depths, life was teeming around these smoky, chimney-like vents.

In the past 46 years of research, however, no one had ever thought to look for life beneath the ocean's hot springs.

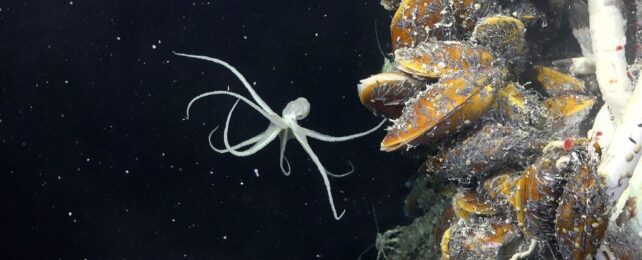

Stripping back the seafloor's shell has now revealed a colorful ecosystem of worms, snails, and chemosynthetic bacteria, which don't rely on sunlight but on minerals for energy.

"Our understanding of animal life at deep-sea hydrothermal vents has greatly expanded with this discovery, " says ecologist Monika Bright from the University of Vienna.

"Two dynamic vent habitats exist. Vent animals above and below the surface thrive together in unison, depending on vent fluid from below and oxygen in the seawater from above."

Scientists found tubeworms particularly fascinating. These deep-sea creatures seem to travel underneath the seafloor through volcanic fluids to colonize new habitats.

This could explain why so few of their young are ever seen congregating around deep volcanic fissures. Most may be maturing below the surface.

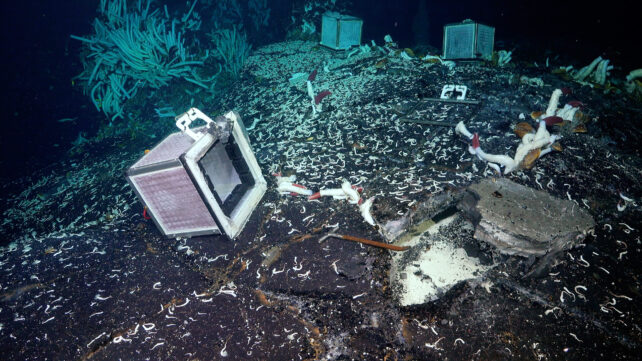

To test this hypothesis, researchers used a remotely operated vehicle, called SuBastian, to clear a square of ocean floor on the East Pacific Rise off Central America, roughly 2,500 meters deep. The team then glued a mesh box over the top of this now lifeless site.

When they removed the box a few days later, researchers found new animals had colonized the area. They must have arrived there from beneath the seafloor's many cracks and fissures.

The results of these findings will be published in the coming months, but if what researchers say is true, then future deep-sea mining excavations could profoundly disturb this newly found ecosystem.

"The discoveries made on each Schmidt Ocean Institute expedition reinforce the urgency of fully exploring our ocean so we know what exists in the deep sea," says Wendy Schmidt, president and co-founder of the Schmidt Ocean Institute.

"The discovery of new creatures, landscapes, and now, an entirely new ecosystem underscores just how much we have yet to discover about our Ocean–and how important it is to protect what we don't yet know or understand."