Scientists are making preparations to send a transmission to Proxima b - the closest Earth-like exoplanet to our Solar System.

The team is putting together a plan to build or buy a powerful deep-space transmitter, and is now figuring out what our message should be - after all, we don't want to make a bad first impression.

"If we want to start an exchange over the course of many generations, we want to learn and share information," president of the San Francisco-based Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) organisation, Douglas Vakoch, told The Mercury News.

METI's plan is similar to that of the former NASA mission, Project Cyclops, which was backed by the space agency but shelved in the 1970s due to a lack of funding.

Project Cyclops proposed patching together a network of radio telescopes on Earth to reach out as far as 1,000 light-years into space, and METI has similar ambitions.

The non-profit organisation is planning a series of workshops and a crowdfunding drive to make the scheme a reality - and it's estimated they'll need to raise around US$1 million a year to run the transmitter.

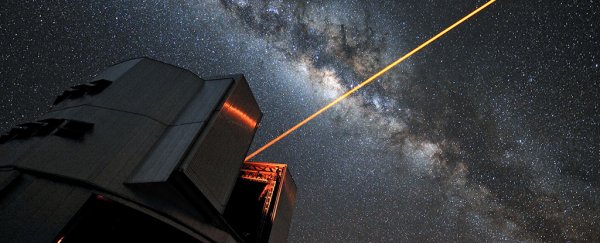

By 2018, the team wants to have laser or radio signals beamed out to Proxima b, which orbits Proxima Centauri - the closest star to our Solar System, at around 4.25 light-years away.

Part of METI's work will be to figure out what we should say, and to consider the possibility that other lifeforms will have developed the same mathematical laws and scientific hypotheses that we have.

The researchers at METI also want to reassess the Drake equation, written in 1961 by astrophysicist Frank Drake to calculate how many other civilisations there could be in the Universe, based on factors like star formation rates and the ratio of planets to stars.

But not everyone agrees that broadcasting our existence into the unknown is a such a good idea: in a recent paper in Nature Physics, physicist Mark Buchanan argued that we might be "searching for trouble" if we start flinging messages out into space.

Stephen Hawking agrees, recently arguing that it's too risky to try and chat to civilisations that are probably far more advanced than we are - lifeforms that could have the same opinion of us that we have of bacteria.

Despite the opposition, the experts at METI are convinced that the benefits of reaching out into space and learning more about our place in the Universe outweigh the risks.

"Perhaps for some civilisations… we need to take the initiative to make first contact," Vakoch writes in Nature Physics.

"The role of scientists is to test hypotheses. Through METI we can empirically test the hypothesis that transmitting an intentional signal will elicit a reply."

It won't be the first time we've sent messages out into the void, but METI is planning communications that are more regular and will reach further than ever before.

Perhaps the best argument for METI's scheme is that someone needs to make the first move, as astronomer Andrew Fraknoi from Foothill College in California, told The Mercury Times.

"If everyone who can send a message decides only to receive messages, it will be a very quiet galaxy," he says.