When it comes to figuring out exactly how and when life evolved on Earth, it's going to take a lot of great minds working together.

To help make that process easier, a team of 20 palaeontologists, molecular biologists and computer scientists, including researchers from Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Australia, has just launched a huge online database of fossils from around the world - and they're hoping it'll help us piece together when and how groups of plants and animals first evolved.

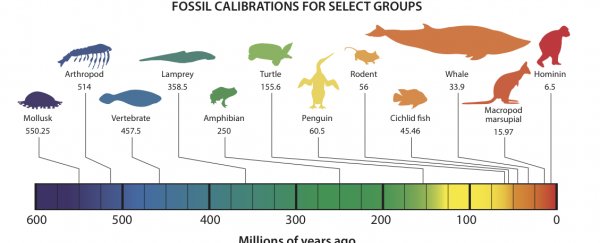

Known as the Fossil Calibration Database, the free, online resource will be used to help date the branching points of the tree of life, and better map the origin of humans, plants and animals. It's the world's first open-access fossil database for molecular dating.

The database brings together peer-reviewed fossil information, and it will help scientists from around the world calibrate their 'molecular clocks'.

Right now, scientists compare changes between the DNA of living species to map out how long ago they diverged on life's family tree. But by comparing this information to the fossil record, they can get some sense of a timescale, and hopefully will be able to one day date all of the branching points on the tree of life.

"Molecular dating uses fossils as calibrations to inform our models of how the rate of DNA evolution varies among species, to estimate the time key groups of plants and animals evolved," said Matthew Phillips, an evolutionary biologist from QUT, in a press release.

He explains that up until now, a lot of these evolutionary genetic studies have been calibrated using outdated and sometimes even incorrect fossil data.

"There has been a lot of disagreement between fossil and DNA researchers on the timing of major events in life's history," added Phillips in the release. "But the new database will help them find common ground by providing molecular biologists with carefully vetted fossil data for organisms right across the tree of life."

Phillips earlier work managed to show that echidnas, which are monotremes, were descended from ancient platypuses, and he contributed this information to the database. But scientists still aren't sure when marsupials first appeared, and he's hoping the rest of the data might help him figure this out.

The project was led by Daniel Ksepka, a science curator at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, US, and will be hosted by the journal Palaeontologia Electronica. In addition to being a resource for scientists, it will also provide the public with peer-reviewed evidence so that they can make their own minds up about alternative hypotheses.

"Fossils provide the critical age data we need to unlock the timing of major evolutionary events," said Ksepka in a Indiana University press release. "Precisely tuning the molecular clock with fossils is the best way we have to tell evolutionary time."

The only downside is we just spent about two hours browsing fossil records. Explore the database here at your own risk.

Love science? Find out more about the groundbreaking research happening at QUT.

Sources: QUT, Indiana University