When you hear about X-rays, your mind probably jumps to the dentist office or a hospital wing because, for many, many years now, X-rays have been used to look inside things. But now, X-rays are being increasingly used in other areas of research, and the latest involves using them to measure the motion and velocity of hard-to-measure atoms.

According to a new study, X-rays can clock the speeds of atomic particles in the same way that police can clock a speeding driver's using a radar gun. "It's a bit like a police speed trap - for atomic and nanoscale defects," says one of the researchers, Randall Headrick from the University of Vermont,

The new technique was developed when Headrick and his team noticed how hard it is to get a clear picture of things on the nanoscale. Basically, X-rays can look inside nearly everything from our bodies to atoms.

But when you get to the atomic scale, their insides are chaotic, complex, and disordered, which, in the end, leads to a blurry picture. Headrick says using this old technique is like "trying to see what an average car looks like by watching traffic zip along a highway".

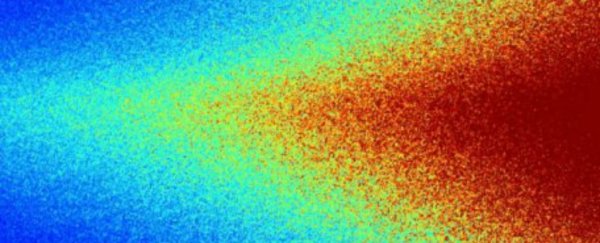

To solve this problem, the researchers found a way to manipulate coherent X-rays. That means they set up the X-rays in an orderly, controlled fashion instead of all over the place (like "X-rays in a marching band", they say) to capture information onto very thin film strips. On these film sheets, the team discovered small pores and voids forming that, with further study, could tell them about the object they X-rayed.

These pores and voids develop both internally and externally on the film strips. "We find that there are two kinds of defects, one type that moves along with the surface and are thought to be nanocolumns that grow with the surface - and another type that are voids that do not grow with the surface," said Headricks.

Using this technique, researchers can effectively make order out of chaos or, to put it another way, make chaos easier to study. This information can also be used to gauge speeds at the atomic scale. Basically, they can watch these pores and voids form internally and externally and use it as a speed trap for quickly moving atoms.

Besides offering a new way to look inside things at such a small scale, the team also says their discovery will lead to the creation of better thin film strips for us in a plethora of different areas from chip bags to computer chips.

The team's research was published in Nature Physics.