A supermassive black hole growing so fast it shines 7,000 times brighter than the entire Milky Way has just been found, hiding in plain sight.

Every second, an amount of material equivalent to the mass of Earth falls into this insatiable black hole.

As far as we know, it's the fastest-growing black hole of the last 9 billion years – its activity so frenzied that it sends multi-wavelength light blazing across the Universe, making it what's known as a quasar.

The black hole is called SMSS J114447.77-430859.3 – J1144 for short – and an analysis of its properties suggests that the light from its feeding has traveled some 7 billion years to reach us, and that it clocks in at around 2.6 billion times the mass of the Sun (quite a respectable size for a supermassive black hole).

And there it was, just hanging out, lurking unnoticed until now. But because of where it sits – 18 degrees above the galactic plane – previous surveys looking for quasars have just managed to miss it, only skimming as close as 20 degrees above the disk of the Milky Way.

"A bit of historical bad luck has become our good luck," astronomer Christopher Onken from the Australian National University told ScienceAlert.

"Searches for distant objects get very difficult when you look close to the disk of the Milky Way – there are so many foreground stars that it's very hard to find the rare background sources.

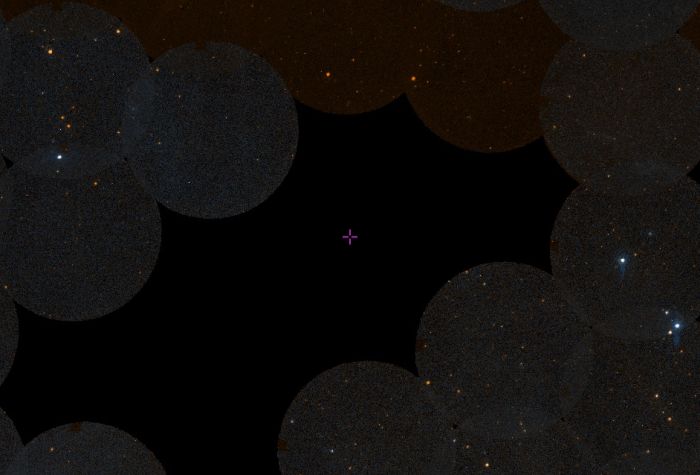

"Another team used an ultraviolet satellite to search for these luminous objects across the whole sky, but J1144 fell into a small gap in their coverage. But the source is bright enough that it appears in photographs taken of the sky as far back as 1901, so it's definitely a case of hiding in plain sight."

The gap in the ultraviolet survey. (Christopher Onken)

The gap in the ultraviolet survey. (Christopher Onken)

Apart from supernova explosions that emit gamma-ray bursts, quasars are the brightest single objects in the Universe. They are the result of a supermassive black hole accreting matter at a tremendous rate, from an enormous disk of dust and gas that spirals into the black hole like water down a drain.

It's not the black hole itself that glows, but that material, heated by extreme friction and gravity, producing light across the spectrum.

In addition, astronomers think that some of the material can be channeled and accelerated along magnetic field lines around the outside of the black hole to the poles, where it is launched into space as high-speed jets of plasma. The interaction of these jets with gas in the surrounding galaxy produces radio waves.

But there's something really odd about J1144. Quasars with the same level activity can be found, but much earlier in the Universe's history, which goes back around 13.8 billion years.

After about 9 billion years ago, this furious quasar activity seems to have calmed down somewhat, making J1144 a fascinating weirdo. The quasar is so bright that someone with a backyard telescope could go out and look at it with their own eyes.

"This black hole is such an outlier that while you should never say never, I don't believe we will find another one like this," says astronomer Christian Wolf of ANU.

"We are fairly confident this record will not be broken. We have essentially run out of sky where objects like this could be hiding."

But the discovery has prompted new fervor for hunting down and compiling a census of bright quasars. Already the team has confirmed 80 new quasars, with hundreds more candidates to be analyzed and confirmed or ruled out.

This means that the astronomical community is close to a complete census of bright quasars in the relatively recent Universe.

"None of them are as bright as J1144, but they'll help paint a more complete picture of how common this rapid growth phase might be, and that will help us to understand the physical mechanism behind it," Onken told ScienceAlert.

"Whether it's rare collisions between enormous galaxies, or something special about the environment right around the black hole, or actually about the black hole itself – for example, a rapidly spinning black hole can release much more energy from the matter it accretes than one that is hardly spinning at all."

In addition, because they are so bright, the light from quasars can be analyzed to learn more about the tenuous gas that drifts between the galaxies, Onken said.

This can reveal the flow of gas around the Milky Way galaxy itself, giving us a better understanding of the three-dimensional movements in the space around us.

The team's research has been submitted to the Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, and is available on preprint server arXiv.