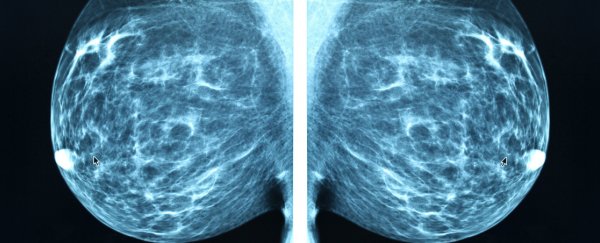

Scientists have found a mechanism that might help them stop breast cancer from spreading to the bones - a breakthrough that could improve survival rates of thousands of patients each year. And even more excitingly, they've also found an existing drug that can stop the metastasis from happening in mice.

The team found that before a tumour spreads, it releases an enzyme that starts breaking down bone tissue and forming holes, essentially preparing them for the arrival of the cancer cells. They now hope that by blocking this enzyme, known as LysYl Oxidase or LOX, they might be able to stop the disease progression in certain patients.

Publishing in Nature, the researchers explain that the results could help the almost 12,000 people in the UK, 40,000 in the US, and 3,000 in Australia who die from breast cancer each year. The majority of these deaths occur after the disease has spread to other parts of the body, a process known as metastasis - and in roughly 85 percent of these cases, the bone is the first site that breast cancer attacks.

"We are really excited about our results that show breast cancer tumours send out signals to destroy the bone before cancer cells get there in order to prepare the bone for the cancer cells' arrival," one of the lead researchers, Alison Gartland, from the University of Sheffield in the UK, said in a press release.

"This is important progress in the fight against breast cancer metastasis and these findings could lead to new treatments to stop secondary breast tumours growing in the bone, increasing the chances of survival for thousands of patients."

The researchers also showed that, in mice, a class of drugs called bisphosphonates, which are used to treat bone mass loss in osteoporosis patients, was able to prevent the holes forming in the bones and stop the spread of breast cancer.

The discovery only applies to the roughly one-third of patients that have oestrogen receptor negative (ER negative) breast cancer, which is particularly hard for doctors to treat. But the research will help scientists understand more about how other cancers prepare to spread around the body.

"The next step is to find out exactly how the tumour secreted LOX interacts with bone cells to be able to develop new drugs to stop the formation of the bone lesions and cancer metastasis," said Gartland. The research could also lead to new treatments for debilitating bone conditions.

"The reality of living with secondary breast cancer in the bone is a stark one, which leaves many women with bone pain and fractures that need extensive surgery just when they need to be making the most of the time they have left with friends and family," said Katherine Woods from the Breast Cancer Campaign that partly funded the research.