NASA astronomers have used data from the Voyager probes to measure the bustle of particles rippling at the very edge of our Solar System, and discovered the pressure in the distant borderlands of our star is higher than they expected.

The results suggest "that there are some other parts to the pressure that aren't being considered right now that could contribute," says Princeton University astrophysicist Jamie Rankin.

Maybe there are entire populations of particles out there that haven't been taken into account yet. Or maybe it's just a little hotter than anybody figured. The researchers have a number of possible explanations to explore in future research.

While the discovery itself is interesting enough, it's the way they found it that makes for a truly fascinating bit of science.

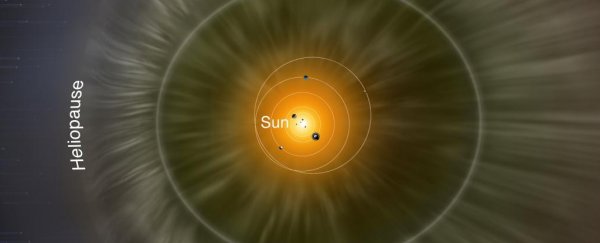

As plasma in the shape of solar wind emanates from our Sun, it forms a 'bubble' we call the heliosphere. Fourteen billion kilometres away from the star, that wind effectively runs out of steam, as charged particles rapidly slow to subsonic speeds.

The edge of this bubble, called the heliosheath, is a zone where the density of those charged particles drops off and magnetic fields grow weak.

Beyond this messy border is a thin shell called the heliopause, where the haze of plasma blown out by the Sun trickles away, nudged by the subtle influence of our galactic neighbours as our star moves through space.

At this 'pause', the pressure of local interstellar space pushing in and the heliosheath pushing out must balance out. Knowing exactly what this looks like, though, is no easy task. We can make models to estimate, but nothing beats hard evidence.

Fortunately, we happen to have two probes passing through that part of the Solar System. Take a look at NASA's handy diagram below to see how it all fits together.

(NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Mary Pat Hrybyk-Keith)

(NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/Mary Pat Hrybyk-Keith)

Voyager 1 is about 20 billion kilometres away, effectively out in the wild emptiness we think of as interstellar space. Its partner, Voyager 2, isn't far behind, right on the cusp of making an exit.

Neither has a direct way of telling us much about the pressures of space in that area, but a recent flare-up in solar activity called a global merged interaction region (GMIR) provided a prime opportunity to work it out.

"There was really unique timing for this event because we saw it right after Voyager 1 crossed into the local interstellar space," says Rankin.

"And while this is the first event that Voyager saw, there are more in the data that we can continue to look at to see how things in the heliosheath and interstellar space are changing over time."

The solar activity was effectively a shout into space, sending a pulse of particles roaring out into the distance. This cry rippled into the heliosheath in 2012, where Voyager 2 was watching and listening. Roughly three months later, Voyager 1 also felt its effects.

From each set of observations, the researchers calculated the pressure at the boundary to be around 267 femtopascals, which is an absolutely minuscule fraction of the kind of atmospheric pressure we experience here on Earth.

It might be a relatively tiny squeeze, but the researchers were surprised.

"In adding up the pieces known from previous studies, we found our new value is still larger than what's been measured so far," says Rankin.

The team were also able to calculate the speed of sound waves passing through this medium – a speedy 314 kilometres per second. Or a thousand times faster than sound travelling through our own atmosphere.

There was one other surprise to come. The wave's passage lined up with an apparent drop in the intensity of high speed particles called cosmic rays. The fact each of the probes experienced this same thing in two different ways gives astrophysicists yet another mystery to solve.

"Trying to understand why the change in the cosmic rays is different inside and outside of the heliosheath remains an open question," says Rankin.

The Voyager probes might be getting a little old, but given how busy it looks out on the edge of the Solar System, we're glad they haven't fully retired yet.

This research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.