Humans are spending more time in outer space than ever, and we're bringing our gonads with us. But scientists are concerned that sexual health in space is a 'policy blind spot' that needs to be taken more seriously.

Spending extended time in space wreaks havoc on the body: cosmic radiation is unavoidable, microgravity makes everything a bit too effortless, and all the usual cues for knowing what time it is go totally out the window.

There's plenty of research about these safe-for-work side effects, but whether it's because of priorities or due to prudishness, reproductive health remains a blind spot.

In a review led by University of Leeds embryologist Giles Palmer, nine scientists have expressed their concern about just how little we know, at a time when commercial and frequent spaceflight is ramping up.

"Despite over 65 years of human spaceflight activities, little is known of the impact of the space environment on the human reproductive systems during long-duration missions," Palmer and team write.

What few laboratory and human studies have been conducted suggest space is indeed a hostile place for Earthling reproductive systems.

The main problem is those pesky cosmic rays, particles from outer space that can accidentally edit our DNA as they fly by. Much like radiation exposure on Earth, if those 'cosmic typos' occur in a sperm or egg cell that goes on to form an embryo, it could have major ramifications.

Animal studies have also shown that short-term exposure to radiation disrupts menstrual cycles and increases cancer risk, but when it comes to longer space missions, there's very little reliable data from actual humans.

And, after their review of the existing research, Palmer and team concluded we know next to nothing about the effects repeated exposure to radiation has on male fertility.

One study suggests doses of radiation exceeding approximately 250 mGy can disrupt the formation of sperm, although this may be reversible. Another speculates that longer missions could have more serious effects on the neuroendocrine system that regulates reproductive hormones.

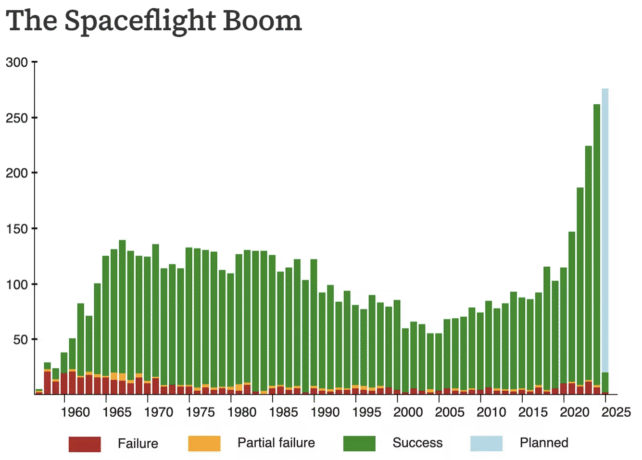

We're launching more rockets than ever into space, thanks to growing commercial investment in spaceflight and falling costs as technology improves.

While missions sent by NASA and other public agencies have upheld strict rules around sexual health in space, these might not be possible – or ethical – for commercial companies to enforce.

Space agency-sponsored astronauts, for example, cannot travel into space if pregnant, and there are usually limits for the allowable radiation exposure an astronaut can endure.

These regulations come with their own problems. For instance, NASA set radiation exposure limits for astronauts in low Earth orbit at 50 mSv per year, but the limit was set lower for women since the risk was higher for ovarian and breast cancer. Though the risk is real, legal scholars say these double standards may also amount to gender-based discrimination.

Related: Exposure to Microgravity Seems to Seriously Disorient Human Sperm

But when it comes to commercial spaceflight, Palmer and team are more concerned about a lack of regulation entirely. At present, there are no industry-wide standards for managing the risks to reproductive health.

"Should they monitor pregnancy status in employees? In commercial travellers and tourists?" they ask.

"Should informed consent forms include estimations of altered long-term risks for reproductive success, and for possible damage to a fetus?"

The fact is, until we know more about the reproductive impacts of spaceflight, it will be difficult to warn prospective passengers and employees of the risks.

"As human presence in space expands, reproductive health can no longer remain a policy blind spot," says NASA research scientist Fathi Karouia, a senior author of the study.

"International collaboration is urgently needed to close critical knowledge gaps and establish ethical guidelines that protect both professional and private astronauts – and ultimately safeguard humanity as we move toward a sustained presence beyond Earth."

The research was published in Reproductive Biomedicine Online.