Scientists have identified a new mechanism that could lead to the development of Alzheimer's disease, suggesting that a leaky blood-brain barrier might be a key factor in the early stages of the condition.

The blood-brain barrier acts as a defensive shield for our brains, stopping unwanted invaders from reaching the brain tissue, and making sure the right level of nutrients are allowed through. It serves as a kind of border patrol for one of our most vital organs, so it makes sense that a loosening of biological security procedures could be linked to disease.

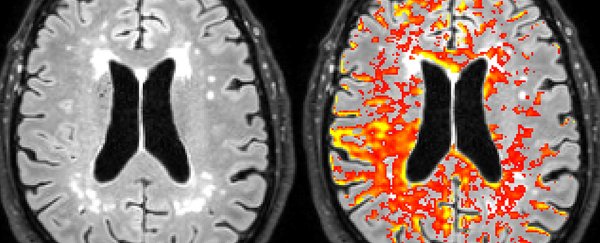

A team led by radiologist Walter H. Backes from the Maastricht University Medical Centre in the Netherlands carried out MRI scans on 16 patients with early signs of Alzheimer's and 17 healthy people without symptoms of the disease. The leakage rates of the blood-brain barrier were measured and plotted on a histogram for comparison.

The results showed that blood-brain barrier leakage was significantly higher in the people with Alzheimer's, and the leakage was distributed throughout the cerebrum – the largest part of the brain located at the front of the skull.

Higher amounts of leaking brain tissue were found in both grey matter and white matter, which together make up the central nervous system, as well as the cortex – the brain's outer layer.

"Blood-brain barrier leakage means that the brain has lost its protective means, the stability of brain cells is disrupted, and the environment in which nerve cells interact becomes ill-conditioned," said Backes. "These mechanisms could eventually lead to dysfunction in the brain."

The researchers also found a relationship between the extent of blood-brain barrier impairment and a decline in cognitive performance, providing further evidence that deteriorations in this barrier could be linked with the early onset of Alzheimer's.

According to Backes, the discovery could help diagnose Alzheimer's at an earlier stage. "For Alzheimer's research, this means that a novel tool has become available to study the contribution of blood-brain barrier impairment in the brain to disease onset and progression in early stages or pre-stages of dementia," he said.

The researchers hypothesise that certain molecules that couldn't cross a healthy blood-brain barrier are finding their way through in the case of Alzheimer's patients, creating a toxic accumulation of substances that ultimately causes damage to the brain.

While the number of patients analysed for the study is relatively small, the findings, published in Radiology, could provide important leads for future research.

The next step will be to show some kind of causality, and identify when in the development of Alzheimer's the leaks actually start happening. "[The researchers] don't know whether this leakage is a result of the disease, or a cause of it," neurologist Ezriel Kornel from Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, who was not involved in the study, told Amy Norton at HealthDay.

According to researcher David Morgan of the University of South Florida, who also wasn't a part of the study, the leaky blood-brain barrier could actually be used to our advantage, if it allows through medications that would otherwise be blocked.

"If Alzheimer's patients do have a leaky blood-brain barrier, in a strange way, that could be a good thing," he told HealthDay. "Some therapies that are under development might have a better chance of working."