Humans were migrating to early medieval England from much further afield than scientists once thought.

Genetic analysis at a cemetery in Dorset and another in Kent has now revealed the skeletons of two individuals from the seventh century with ancestry all the way from West Africa.

Based on the DNA of the young woman and the man, their relatives migrated to southern Britain in late antiquity – a century or two after the eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire, reasserted control over North Africa.

Related: DNA From Beethoven's Hair Reveals a Surprise Close to 200 Years Later

Both individuals show clear signs of non-European ancestry, revealing 20 to 40 percent affinity with groups in present-day West Africa.

Their intercontinental ancestors go back two to four generations, which means their grandparents probably left the southern parts of North Africa between the mid-6th and the early 7th centuries.

"Our joint results emphasize the cosmopolitan nature of England in the early medieval period, pointing to a diverse population with far-flung connections who were, nonetheless, fully integrated into the fabric of daily life," says archaeologist Ceiridwen Edwards from the University of Huddersfield in the UK.

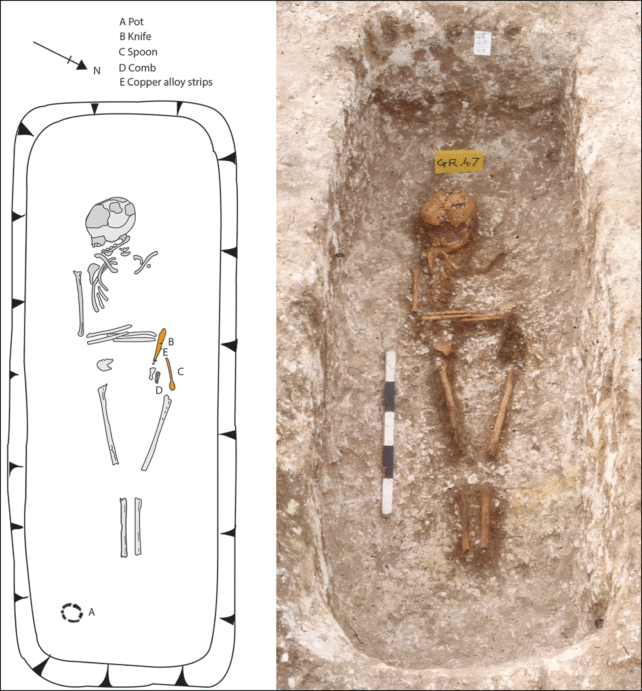

The young woman with African ancestry was buried in Kent in a typical fashion for the time and place. She died on the brink of adolescence, and she was buried alongside a knife, a comb, and a decorated pot, which possibly had amuletic or ritual properties, and which suggest that she was a valued member of society. The eclectic collection mirrors her diverse heritage.

The woman's mitochondrial DNA indicates that she had a mother from northern Europe. But her autosomal DNA reveals clear signs of non-European ancestry.

According to an international team of researchers, led by archaeologist Duncan Sayer at the University of Lancashire, a significant portion of the young woman's DNA is similar to groups in present-day West Africa.

The man buried in Dorset is also a clear genetic outlier. In a second paper, led by archaeogeneticist George Foody from the University of Huddersfield, researchers explain that the man's mother is European, but his paternal line is consistent with West African ancestry.

Based on DNA analysis, he and the young woman buried in Kent probably each had a grandfather from West Africa. The male immigrants and their later descendants seem to have fully integrated into early medieval societies in Britain.

The burials of their descendants are no different to anyone else.

"It is significant that it is human DNA – and therefore the movement of people, and not just objects – that is now starting to reveal the nature of long-distance interaction to the continent, Byzantium, and [Africa]," says Sayer.

"What is fascinating about these two individuals is that this international connection is found in both the east and west of Britain. Updown is right in the center of the early Anglo-Saxon cultural zone and Worth Matravers, by contrast, is just outside its periphery in the sub-Roman west."

The findings suggest that Byzantine control of North Africa facilitated distinct gene exchanges between very distant populations.

The Byzantine Empire's control extended all the way to England and North Africa, creating a bridge between the two regions of people, through which gold, costumes, and jewelry flowed.

It seems the connection also allowed for migrant travel.

"This study has greatly enhanced our interpretation of the archaeological results by revealing not only fascinating family dynamics, but also exciting long-distance links between groups and individuals," says archaeologist Lilian Ladle, director of the excavations at Dorset.

It's incredible what the DNA of just two individuals can tell us about people and empires lost to time.

The studies on the individuals from Dorset and Kent are published in Antiquity.