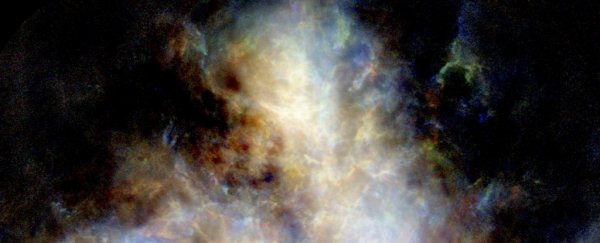

Nearly 200,000 light-years from Earth, the Small Magellanic Cloud is dying. Slowly, over vast time, the galaxy is losing its ability to form new stars - eventually to fade into a wisp of intergalactic gas.

And, thanks to the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), astronomers have borne witness to this demise in the finest detail yet.

"We were able to observe a powerful outflow of hydrogen gas from the Small Magellanic Cloud," said astronomer Naomi McClure-Griffiths from Australian National University.

"The implication is the galaxy may eventually stop being able to form new stars if it loses all of its gas. Galaxies that stop forming stars gradually fade away into oblivion. It's sort of a slow death for a galaxy."

The Small Magellanic Cloud is absolutely tiny, just 7,000 light-years across - less than a tenth of the size of the Milky Way. But, visible to the naked eye in the Southern Hemisphere, it's a beloved part of our night sky.

It's one of a number of satellite galaxies orbiting the Milky Way, and paired with the Large Magellanic Cloud as a sort of binary galaxy system, with the two dwarf galaxies orbiting each other as they orbit the Milky Way.

It's been hypothesised that dwarf galaxies like these play a critical role in the evolution of the Universe.

This happens through something called stellar feedback - when massive stars drive powerful outflows of gas, energy, mass and metals into the intergalactic medium through stellar winds and supernova explosions.

This then enriches the intergalactic medium and regulates star formation - but it's not easy to observe in action.

Leveraging ASKAP's incredibly wide field of view, McClure-Griffiths and her team took observations of the Small Magellanic Cloud as part of an ongoing investigation into the evolution of galaxies.

They were able to observe the entire galaxy in a single shot, allowing an unprecedented look at its atomic hydrogen outflows - a critical ingredient for star formation - and the first clear measurement of the amount of mass lost from a dwarf galaxy.

In their paper, the team was able to demonstrate that outflows of cold atomic hydrogen extended at least two kiloparsecs (6,523 light-years) from the star-forming bar of the galaxy. At an estimate, the outflows formed around 25-60 million years ago.

And they're bleeding out of the galaxy at a tremendous rate. They contain around 10 million solar masses of gas, or around 3 percent of the galaxy's total atomic gas.

The inferred mass flux of the atomic gas, the researchers said, is at least an order of magnitude higher than the star formation rate. The Small Magellanic Cloud is blasting away its atomic hydrogen faster than it's making new stars.

This is bad news for the Small Magellanic Cloud's survival - but it might be good news for the surrounding space, as well as for the astronomers who hunt for evidence of stellar feedback from dwarf galaxies.

"The result is also important because it provides a possible source of gas for the enormous Magellanic Stream that encircles the Milky Way," McClure-Griffiths said.

But, she added, "ultimately, the Small Magellanic Cloud is likely to eventually be gobbled up by our Milky Way."

We'll be sure to give its orphaned stars a good home.

The team's research has been published in the journal Nature Astronomy.