Researchers have identified a period of sluggish magnetic field flipping for planet Earth, some 40 million years ago – raising big questions about how long these reversals actually take, and how we might be affected by the next one.

Magnetic field flips are thought to happen fairly regularly, as far as geological timescales go. There have been some 540 reversals across the last 170 million years, and it seems they've been happening for billions of years.

But something was different 40 million years ago. One transition around this time took 18,000 years, and another took at least 70,000 years, the international team of researchers found, which is far longer than the typical timespan of 10,000 years or so that scientists think is the norm.

"This finding unveiled an extraordinarily prolonged reversal process, challenging conventional understanding and leaving us genuinely astonished," writes lead author and paleomagnetist Yuhji Yamamoto from Kochi University in Japan.

"The variability in reversal duration revealed by this study reflects the intrinsic dynamical properties of the Earth's geodynamo, and it provides empirical evidence that geomagnetic reversals can last significantly longer than the widely assumed 10,000-year duration."

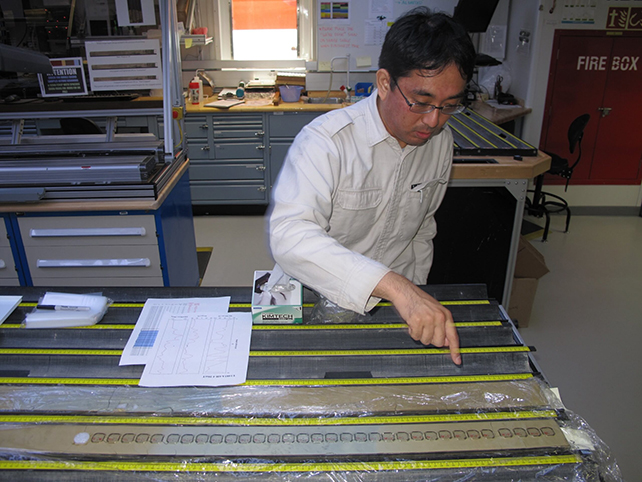

The team analyzed a sediment core extracted from a location off the coast of Newfoundland in the North Atlantic. The magnetic signals inside these cores, locked to tiny crystals, reveal the direction of Earth's magnetic field over vast time periods.

In this case, the researchers looked closely at a specific layer measuring 8 meters (a little over 26 feet) top to bottom, representing part of the Eocene era. There was a clear shift in polarity, but across an unexpectedly large section of the sediment core.

Two magnetic field flips were discovered, one lasting around 18,000 years, and another lasting 70,000 years. Computer modeling suggested events like these could potentially stretch across 130,000 years in some cases – though that's never been seen in the geological record.

These magnetic field flips are driven by shifts in Earth's liquid iron and nickel outer core, around 2,200 kilometers (1,367 miles) thick. While this outer core is always in flux, it occasionally becomes unstable enough that the magnetic poles change position.

The planet doesn't tip over, but magnetic north becomes magnetic south, and vice versa – your compass would eventually point in the opposite direction, after tens of thousands of years of being incredibly confused.

Not only did these newly identified flips take a long time, but they were messier and more variable than the researchers expected. There were multiple 'rebounds' where the magnetic field seemed unsure about which direction to travel in, matching findings from our planet's most recent flip – the Brunhes-Matuyama reversal.

"The occurrence of multiple rebounds is not unprecedented: this behaviour is also reported for the Brunhes-Matuyama reversal," write the researchers in their published paper.

"We suggest that it may be more common and that polarity reversals are inherently complex, if not somewhat chaotic, events."

The Brunhes-Matuyama reversal, which happened around 775,000 years ago, backs up the new findings. A study from 2019 found that the flip took 22,000 years to complete – so drawn-out reversals may be the rule, rather than the exception.

When the next one happens, we need to be ready. One of the consequences of a magnetic field reversal is that our planet gets far less protection from the radiation and geomagnetic activity beaming down from space.

If that exposure is going to last tens of thousands of years longer than previously thought, we need to know about it. It has the potential to disrupt everything from animal species to climate systems – though more research will be needed to know the precise effects.

Related: Signs of Mysterious Structures Near The Core Detected in Earth's Magnetic Field

"It's basically saying we are exposing higher latitudes in particular, but also the entire planet, to greater rates and greater durations of this cosmic radiation," says paleomagnetist Peter Lippert from the University of Utah.

"Therefore, it's logical to expect that there would be higher rates of genetic mutation. There could be atmospheric erosion."

The research has been published in Communications Earth & Environment.