The passage of time may be linear, but the course of human aging is not. Rather than a gradual transition, your life staggers and lurches through the rapid growth of childhood, the plateau of early adulthood, to an acceleration in aging as the decades progress.

Now, a new study has identified a turning point at which that acceleration typically takes place: at around age 50.

After this time, the trajectory at which your tissues and organs age is steeper than the decades preceding, according to a study of proteins in human bodies across a wide range of adult ages – and your veins are among the fastest to decline.

"Based on aging-associated protein changes, we developed tissue-specific proteomic age clocks and characterized organ-level aging trajectories. Temporal analysis revealed an aging inflection around age 50, with blood vessels being a tissue that ages early and is markedly susceptible to aging," writes a team led by scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

"Together, our findings lay the groundwork for a systems-level understanding of human aging through the lens of proteins."

Related: Study Finds Humans Age Faster at 2 Sharp Peaks – Here's When

Humans have a remarkably long lifespan compared to most other mammals, but it comes at some costs. One is a decline in organ function, leading to a rise in risk of chronic disease as the years mount up.

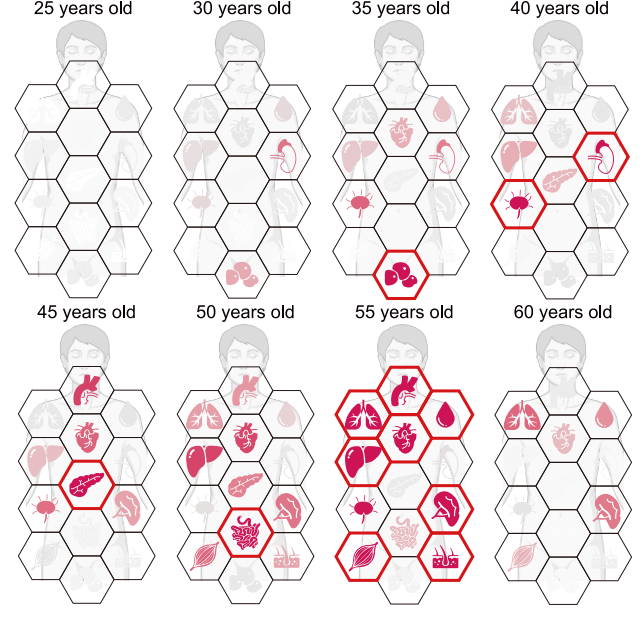

We don't have a very good understanding of the patterns of aging in individual organs, so the researchers investigated how proteins in different tissues change over time. They collected tissue samples from a total of 76 organ donors between the ages of 14 and 68 who had died of accidental traumatic brain injury.

These samples covered seven of the body's systems: cardiovascular (heart and aorta), digestive (liver, pancreas, and intestine), immune (spleen and lymph node), endocrine (adrenal gland and white adipose), respiratory (lung), integumentary (skin), and musculoskeletal (muscle). They also took blood samples.

The team constructed a catalogue of the proteins found in these systems, taking careful note of how their levels changed as the ages of the donors increased. The researchers compared their findings to a database of diseases and their associated genes, and found that expressions of 48 disease-related proteins increased with age.

These included cardiovascular conditions, tissue fibrosis, fatty liver disease, and liver-related tumors.

The most stark changes occurred between the ages of 45 and 55, the researchers found. It's at this point that many tissues undergo substantial proteomic remodeling, with the most marked changes occurring in the aorta – demonstrating a strong susceptibility to aging. The pancreas and spleen also showed sustained change.

To test their findings, the researchers isolated a protein associated with aging in the aortas of mice, and injected it into young mice to observe the results. Test animals treated with the protein had reduced physical performance, decreased grip strength, lower endurance, and lower balance and coordination compared to non-treated mice. They also had prominent markers of vascular aging.

Previous work by other researchers showed another two peaks in aging, at around 44, and again at around 60. The new result suggests that human aging is a complicated, step-wise process involving different systems. Working out how aging is going to affect specific parts of the body at specific times could help develop medical interventions to make the process easier.

"Our study is poised to construct a comprehensive multi-tissue proteomic atlas spanning 50 years of the entire human aging process, elucidating the mechanisms behind proteostasis imbalance in aged organs and revealing both universal and tissue-specific aging patterns," the researchers write.

"These insights may facilitate the development of targeted interventions for aging and age-related diseases, paving the way to improve the health of older adults."

The research has been published in Cell.