An investigation into why blood doesn't always behave as doctors expect has revealed a super-rare mutation in an extremely uncommon variation of blood.

Testing more than 544,000 blood samples in a hospital in Thailand revealed three people carrying a never-before-seen version of the B(A) phenotype – a genetic quirk estimated to occur in about 0.00055 percent of people, or roughly one in 180,000.

This discovery, says a team led by hematologist Janejira Kittivorapart of Mahidol University in Thailand, suggests that there may be more rare blood variants out there, too subtle for standard testing to detect.

Related: Scientists Identified a New Blood Group After a 50-Year Mystery

Human blood is categorized into eight main groups based on the sugars and proteins – or lack thereof – stuck all over your red blood cells.

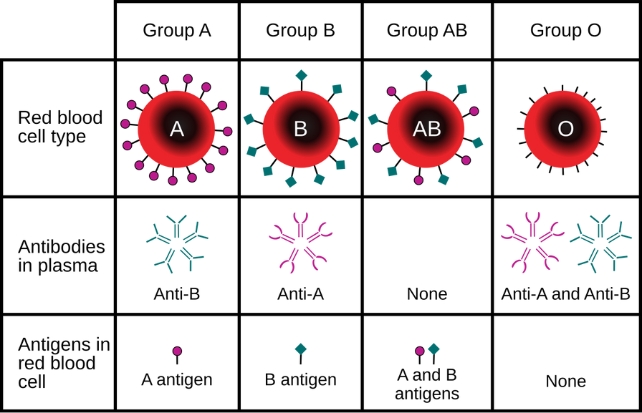

A, B, and AB types are based on the shape of antigens, sugar molecules that can trigger an immune response. O-type blood has no A or B antigens. Meanwhile, rhesus factors are proteins that determine blood compatibility, and are what give your blood its + or - designation.

Each blood type is a molecular marker your body learns to recognize as 'self'. Your immune system uses that recognition to tell which blood types match your own and which look foreign.

If immune cells encounter blood with unfamiliar markers, they can release powerful antibodies to destroy it. This is why blood type is so crucial for transfusions, and why receiving the wrong blood type can kill you.

However, there's a lot more variation in human blood than these eight categories. One such variation is B(A), blood that is type B, but with a few mutations that give its enzyme a tiny amount of A-like activity.

Blood type is determined by looking at two separate components of the blood: antigens on the red blood cells and antibodies in the plasma. Both are important to make sure that a transfusion recipient doesn't receive blood that will make them sick.

Every now and again, however, the red cells and plasma from a single sample return different results – a situation known as an ABO discrepancy. These can cause delays to patient care while the doctors try to untangle what the patient's real blood type is.

Kittivorapart and her colleagues set out to understand how often this happens and why. They carefully examined 285,450 donor and 258,780 patient blood samples collected over eight years at Siriraj Hospital in Thailand, for a total of 544,230 samples.

Just 396 – or 0.15 percent – of the patient samples returned ABO discrepancies. Half of these were excluded from the analysis; they were samples collected from stem cell transplant recipients, whose blood type can temporarily change to that of their donor.

That left 198 patient blood samples with ABO discrepancies, most of which were due to their blood cells not showing either A or B configurations strongly. Only one patient in the entire set had the B(A) phenotype.

The rate of ABO discrepancy among donors was much lower – just 74 samples, or 0.03 percent. That's probably not surprising, since patients receiving treatment for serious illness are probably more likely to have unusual blood behavior than regular donors. Just two donors also had the B(A) phenotype.

Finding just 3 cases in nearly 550,00 samples moved the researchers to investigate those rare cases further.

They found four mutations in the ABO gene, which encodes the enzyme that adds sugar to blood cells, a configuration never before reported. While the blood is technically type B, it has a small amount of A antigen activity that confuses the blood typing test.

Although this affects only a tiny fraction of the population, the results suggest there may be other hidden blood quirks yet to be discovered. It also underscores the value of genetic testing when standard methods are inconclusive.

"Future studies," the researchers concluded, "are required to elucidate the structural and functional consequences of the mutated [enzyme] AB transferase."

Related: How a Medical Mystery Revealed The World's Rarest Blood Type

While new discoveries like this are very rare, this isn't the only time in recent history that scientists have uncovered evidence of blood variations we never knew about.

In 2024, researchers solved a 50-year scientific mystery, identifying that an abnormality in a pregnant woman's blood sample taken in 1972 actually constituted a new blood group system.

Then, earlier this year, researchers in France discovered what appears to be the world's newest and rarest blood group, after routine tests on a single patient from the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe revealed the existence of "Gwada-negative", a blood type never seen before.

The patient "is undoubtedly the only known case in the world," said medical biologist Thierry Peyrard from the French Blood Establishment at the time of the discovery.

"She is the only person in the world who is compatible with herself."

The research on the new B(A) phenotype has been published in Transfusion and Apheresis Science.