Something much closer to home may be behind the seismic signals purported to be caused by an interstellar meteor falling to Earth 10 years ago.

Last year, the meteor made headlines when a team of scientists visited what they considered to be the impact location of the space rock and dredged tiny spherules from the seafloor; debris, they speculated, that contains evidence of alien technology.

A new problem with that claim has now arisen. Seismic monitoring data used to track the hypothetical object's path into the sea off the coast of Papua New Guinea may not show a meteorite hitting the planet, but rather a passing truck rumbling down a nearby road.

"The signal changed directions over time, exactly matching a road that runs past the seismometer," explains planetary seismologist Benjamin Fernando of Johns Hopkins University.

"It's really difficult to take a signal and confirm it is not from something. But what we can do is show that there are lots of signals like this, and show they have all the characteristics we'd expect from a truck and none of the characteristics we'd expect from a meteor."

When a large-enough chunk of rock enters the atmosphere, it can explode before it burns up. Earth is struck by these fireball meteors – known as bolides – a rate of a few dozen per year. Most of them fall over the ocean, but we have pretty sophisticated tracking systems to tell us where they enter the atmosphere, and how powerfully they explode.

One way of tracking particularly hefty bolides is through seismic data, both from vibrations caused by the infrasound waves generated on atmospheric entry and the vibrations when chunks of the exploded rock fall on land.

A meteor named CNEOS 2014-01-08 was tracked by US government satellites entering and streaking through Earth's atmosphere in January 2014. Sensors recorded an anomalously fast velocity that suggested an interstellar origin, so astrophysicists Avi Loeb and Amir Siraj of Harvard University decided to investigate, looking for any traces of the space rock so they could analyze it.

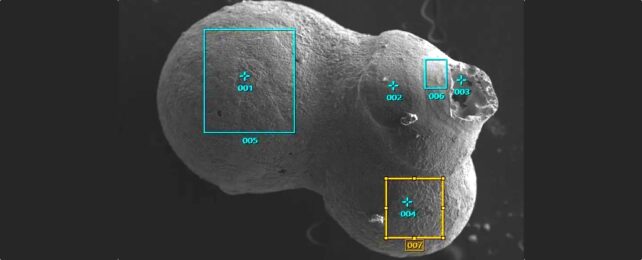

They recovered data from a seismic monitoring station on Manus Island recorded at the time the meteor entered the atmosphere and determined the high speed rock had fallen into an area off the coast of Papua New Guinea. They dredged the seafloor, and found spherules – tiny, microscopic balls of meteor material that form after the bolide heats to the point of melting, shedding little blobs of molten rock that then harden.

However, Fernando and his team noticed something strange about the seismic data the researchers used to refine the trajectory of the bolide. The precision of the trajectory measurement they made was way higher than any other comparable measurements made using data from not one but multiple seismic stations. The relatively small landing area obtained from just a single station pinged their malarkey sensors.

Fernando and his fellow researchers took a closer look at the Manus Island signal, as well as several other monitoring stations around Papua New Guinea and Australia designed to detect sound waves from nuclear testing. Not only did they trace the Manus signal to the nearby road, they found data from the other stations that suggested the meteor fell more than 170 kilometers (106 miles) from the place Loeb and Siraj looked.

"The fireball location was actually very far away from where the oceanographic expedition went to retrieve these meteor fragments," Fernando says. "Not only did they use the wrong signal, they were looking in the wrong place."

It's not uncommon for signals interpreted one way to turn out to be something else. Let's not forget the time radio astronomers were puzzled for decades by a signal that turned out to be a microwave oven. Or an 'exceptional' gamma-ray burst that turned out to be space junk. Humans are really noisy and messy, and teasing out natural signals from the noise we make can be challenging.

But extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Earth is littered with meteoritic spherules; a 2021 study found that some 3,600 tons of cosmic spherules rain down on Earth every year. Spherules dredged out of the ocean 10 years after the fact would be extremely challenging to link to a specific meteor.

In addition, in a preprint published last year, astronomers found that the velocity of CNEOS 2014-01-08 was more than likely greatly overestimated, which means that the evidence for an interstellar origin was probably incorrect to start with.

So, sadly, it's back to the drawing board for robust signs of extraterrestrial intelligence.

"Whatever was found on the seafloor is totally unrelated to this meteor," Fernando says, "regardless of whether it was a natural space rock or a piece of alien spacecraft – even though we strongly suspect that it wasn't aliens."

The team will present their findings at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2024, and you can read their working in a preprint available on arXiv.