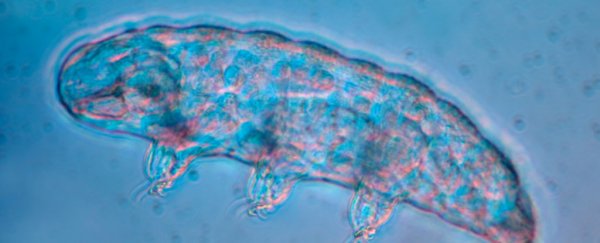

Traveling by snail may not sound like the quickest way to get around, but it's faster than walking … if you're a tardigrade.

Eight-legged, endearingly tubby tardigrades – near-microscopic organisms that are also known as water bears or moss piglets – can hitch rides on land snails to journey farther than they could under their own power, new research finds.

But while snail-surfing helped tardigrades disperse into new locations, a coating of the snails' slimy mucus often proved fatal to tardigrade riders.

Tardigrades measure from 0.002 to 0.05 inches (0.05 to 1.2 millimeters) long and can live nearly anyplace on Earth where there's liquid water: in oceans, in rivers and lakes, and in soggy clumps of lichen and mosses that grow on rocks and trees.

Wee water bears can also endure circumstances that would be fatal to most forms of life, such as extreme temperatures, crushing pressure, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the vacuum of space and even being shot out of a high-speed gun, by exercising a superpower known as anhydrobiosis – expelling nearly all the water in their bodies.

In this desiccated and scrunched-up form, called a tun state, tardigrades can survive punishing conditions and can persist for years; some tardigrade tuns that were frozen for 30 years were successfully resuscitated in 2016 and immediately began reproducing, Live Science previously reported.

And researchers recently found that active and tun-state tardigrades alike could be picked up and carried by land snails that share their habitats.

Related: 8 reasons why we love tardigrades

Though tardigrades can swim and walk, their tiny legs don't carry them very far. A tardigrade in search of a new neighborhood therefore needs outside assistance, such as wind, flowing water or an obliging host animal that's damp enough to keep the traveler alive.

Little is known about how tardigrades interact with snails in their natural habitats, but because water bears often live side by side with land snails (which are famously moist), the researchers suspected that snails could potentially be "perfect vehicles for tardigrades" to travel from place to place, according to a study published April 14 in the journal Scientific Reports.

"Checking available literature, we found out that this topic was almost unexplored," said lead study author Zofia Książkiewicz-Parulska, an assistant professor in the Institute of Environmental Biology at Adam Mickiewicz University (UAM) in Poland, and co-author Milena Roszkowska, a UAM doctoral candidate in the Department of Bioenergetics.

The only prior research on the subject – dating to more than 55 years ago – described observations of tardigrades that traveled by riding inside snails' guts after being eaten, then exiting in the mollusks' feces, the researchers told Live Science in an email.

To test their hitchhiking tardigrade hypothesis, the study authors collected grove snails (Cepaea nemoralis) and Milnesium inceptum tardigrades; the two species coexist in terrestrial ecosystems across Western Europe, and both are at their most active under humid conditions. Grove snails' shells measure up to 0.9 inches (22 mm) in diameter, making the mollusks good candidates for carrying tardigrades, the researchers reported.

In their experiments, the scientists sent snails crawling through drops of water and over pieces of moss containing tardigrades, to see how many "piglets" the snails would pick up.

Active and tun-state tardigrades readily adhered to the snails' slime-covered bodies for short rides; the snails transported 38 tardigrade hitchhikers from water droplets, and they gathered 12 tardigrade riders from moss.

In some of the experiments, the researchers surrounded the tardigrades' watery pool with a physical barrier; in those settings, the only tardigrades that crossed that border did so with help from a snail "vehicle," according to the study.

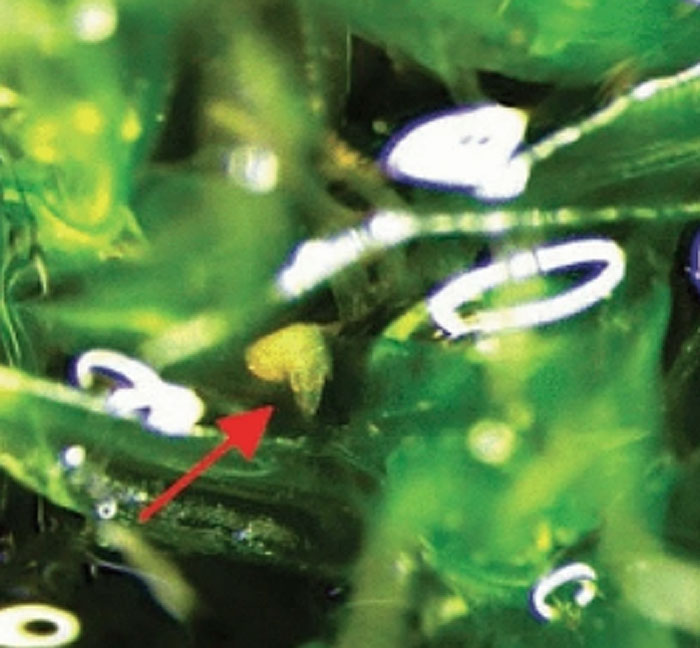

A tardigrade in a rehydrated moss cushion. (Książkiewicz & Roszkowska, Sci. Rep., 2022)

A tardigrade in a rehydrated moss cushion. (Książkiewicz & Roszkowska, Sci. Rep., 2022)

But there was also a deadly downside to the snails' sticky mucus coating, once it dried on the tardigrades' tiny bodies.

Only a fraction of tuns that were coated in dried snail mucus – about 34 percent – could be revived after 24 hours. By comparison, 98 percent of control group tuns that hadn't been slimed became fully active again once they were rehydrated.

Snail mucus is mostly water but it dries quickly, and mucus-coated tuns that were briefly revived by the water in snail slime may not have been able to re-enter a tun state swiftly enough as the slimy envelope around them hardened, and they froze in "very weird poses" that were not fully-formed tuns, the scientists said in the email.

Other forces can transport tardigrades much farther than snails can; prior studies have shown that wind gusts on glaciers can carry tardigrades over distances greater than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers), the study authors wrote.

However, a tardigrade that rides the wind may end up someplace that isn't very hospitable to water bears. A journey by snail is more likely to deposit its rider in an environment that's similar to the one where it started – one where tardigrades (and snails) are likely to thrive.

Further experiments could confirm if tardigrade eggs can hitchhike on snails too, and could test how far a tardigrade might travel by snail, the researchers said.

But even if the traveling tardigrade's new home is just a few centimeters away, that's still far enough to improve genetic diversity among different populations of water bears, according to the study.

That is, as long as the tardigrade hitchhiker avoids being smothered by snail slime before its trip is over.

Related content:

The best gifts for tardigrade lovers

Extreme life on Earth: 8 bizarre creatures

In Photos: The world's freakiest-looking animals

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.