Using the combined might of spacecraft scattered across the Solar System, scientists have built the most detailed map yet of the boundary where the Sun's magnetic push no longer accelerates the solar wind.

It's called the Alfvén surface, and researchers have mapped not only its shape, but also how that shape evolved over the first half of Solar Cycle 25 – the current cycle of solar activity, in which sunspot, flare and coronal mass ejection activity surges to a peak and then wanes over 11 years.

It's the first time this shifting structure has been reconstructed continuously from multi-spacecraft measurements, providing crucial information for understanding the Sun's searingly hot atmosphere.

Related: Astronomers Have Discovered Why The Solar System Might Be Shaped Like a Croissant

"Parker Solar Probe data from deep below the Alfvén surface could help answer big questions about the Sun's corona, like why it's so hot," says astrophysicist Sam Badman of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), first author of the study.

"But to answer those questions, we first need to know exactly where the boundary is."

An astrophysical boundary is usually defined as the point at which the physics governing the behavior of that region changes.

In the case of the Alfvén surface – a boundary scientists have known about for decades – it's the point of no return at which the magnetic influence of the Sun weakens enough that ripples of solar material can no longer propagate back towards the Sun, and the outflowing solar wind is no longer magnetically connected to the Sun.

The solar wind is a stream of particles constantly leaking from the Sun and streaming out through the Solar System. Although it can escape from below the Alfvén surface, the surface is the interface where the wind transitions from magnetically guided flow to a freely streaming outflow.

How that interface froths and spikes, and expands and contracts, influences how it interacts with Earth and the other planets, playing a key role in the space weather that can affect communications technology, power grids, and satellite operations at our home world.

In addition, the Sun is the only star in the entire Universe for which we have the tools to measure the Alfvén surface directly. Well, one tool in particular: the Parker Solar Probe.

Since 2021, Parker has made repeated dives below the Alfvén surface, sending home data that scientists have now determined represents unambiguous sampling of sub-Alfvénic dynamics.

"This work shows without a doubt that Parker Solar Probe is diving deep with every orbit into the region where the solar wind is born," says astronomer Michael Stevens of CfA.

"We are now headed for an exciting period where [the probe] will witness firsthand how those processes change as the Sun goes into the next phase of its activity cycle."

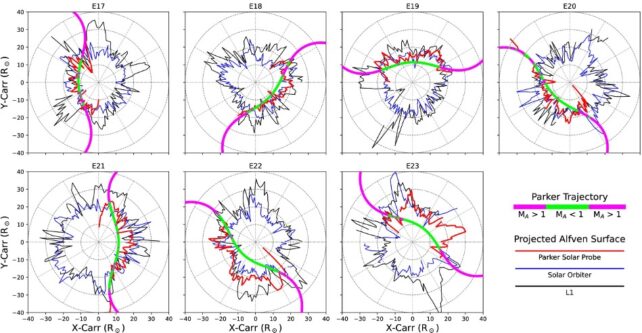

The researchers studied data collected by the probe during perihelion encounters: daredevil plunges deep into the solar atmosphere.

They cross-referenced this data with observations from Solar Orbiter, which studies the Sun from a safer distance, as well as three spacecraft sitting in the L1 Lagrange point, a gravitationally stable region between Earth and the Sun created by the competing gravitational interaction between the two bodies combined with centripetal forces.

These three spacecraft provided data on the speed, density, temperature, and magnetic field of the outflowing solar wind.

The findings revealed that, in most of its perihelion encounters, Parker skimmed bulges in the roiling Alfvén surface.

Only during its two deepest dives, taken in the thick of solar maximum – the peak of the Sun's 11-year activity cycle – did the probe dive deep below the Alfvén surface.

The combined data, taken over six years as the Sun's activity rose in the first half of the solar cycle, also showed that the Alfvén surface expanded by about 30 percent of its median height as solar activity ramped up.

For stronger and weaker solar cycles, the effect is likely to be larger or smaller, accordingly.

"As the Sun goes through activity cycles, what we're seeing is that the shape and height of the Alfvén surface around the Sun is getting larger and also spikier," Badman says.

"That's actually what we predicted in the past, but now we can confirm it directly."

The findings will help scientists understand the physics of the Sun in greater detail, especially with further perihelion data collected by Parker as the Sun subsides into solar minimum.

It also has implications for studying other stars. More strongly magnetic stars, for instance, are likely to have much larger Alfvén boundaries, which would affect closely orbiting worlds and possibly hinder habitability.

"Before, we could only estimate the Sun's boundary from far away without a way to test if we got the right answer, but now we have an accurate map that we can use to navigate it as we study it," Badman says.

"And, importantly, we also are able to watch it as it changes and match those changes with close-up data. That gives us a much clearer idea of what's really happening around the Sun."

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.