In space, no one can hear an asteroid scream. But astronomers just used the Hubble telescope to see one destroying itself.

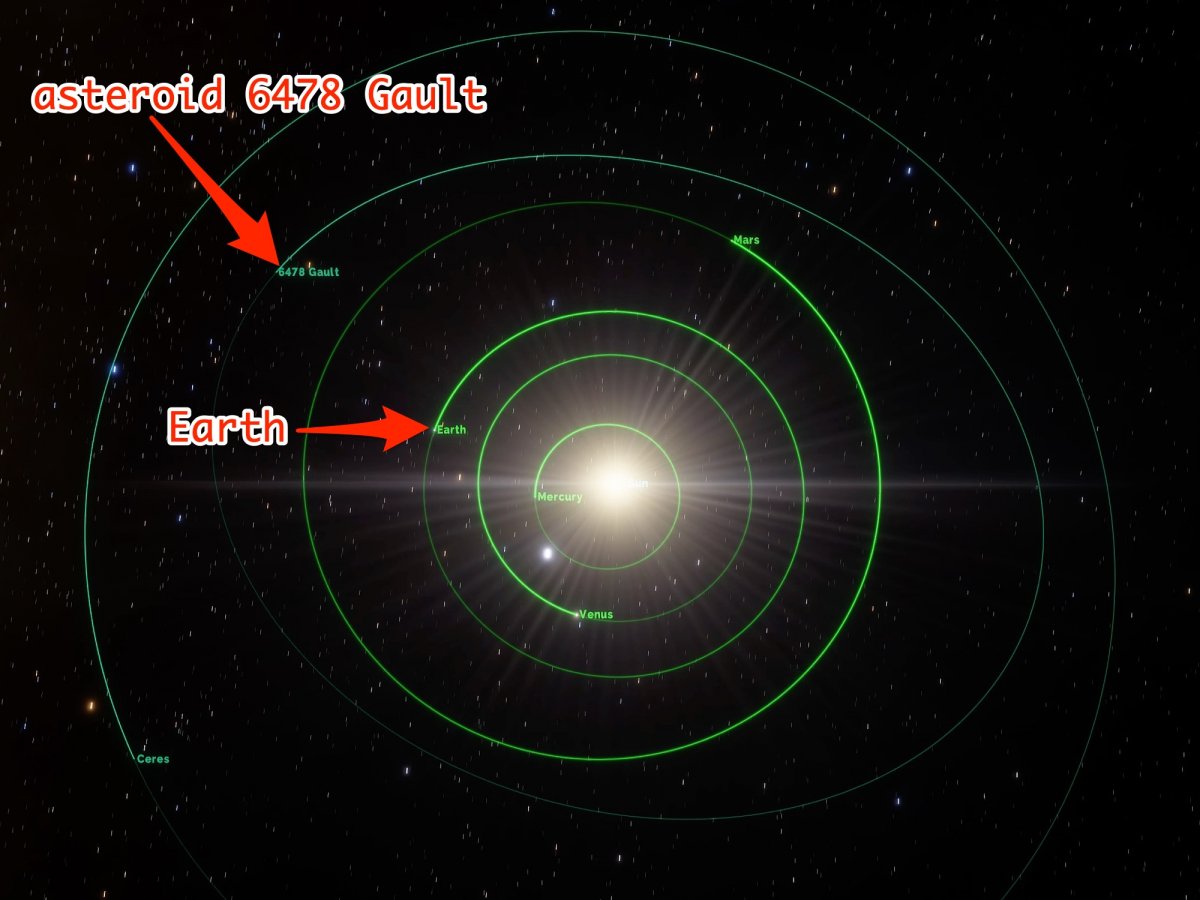

A 2.5-mile-wide (4 kilometer wide) asteroid called 6478 Gault was first discovered in 1988, and it seemed like many of the other 800,000 known space rocks.

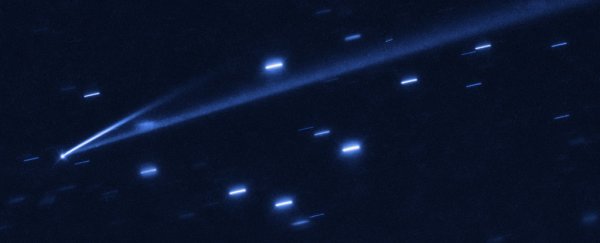

But in January, astronomers saw something strange in survey telescope images: Gault had become "active" and sprouted a big, bright tail – much like a comet's – that stretched more than 500,000 miles (800,000 kilometres) long. A dimmer second tail was found several weeks later.

Some space rocks that initially look like asteroids are later found to be comets when they pass close to the Sun.

The boost in solar energy can warm up ice and other frozen compounds hidden under layers of dust, turning those materials into gases and leading the rock to spew out comet debris to form a long, glowing tail.

Gault didn't seem to fit the bill, though, since it lurks about 214 million miles away from the Sun in a fairly circular orbit between Mars and Jupiter.

In other words, it never swung close to the Sun. So scientists wondered if another space rock had collided with Gault, splashing its dusty guts all over space.

Now, thanks to multiple observations by NASA and the European Space Agency's Hubble Space Telescope, the mystery appears to be solved: Gault is spinning itself to pieces.

"This self-destruction event is rare," Olivier Hainaut, an astronomer with the European Southern Observatory, said in a press release.

"Active and unstable asteroids such as Gault are only now being detected by means of new survey telescopes that scan the entire sky, which means asteroids such as Gault that are misbehaving cannot escape detection any more."

Hainaut and his colleagues around the world have submitted a study about the discovery to Astrophysical Journal Letters, which accepted it for publication in the future.

(ESA/Hubble/Business Insider)The team determined an odd behaviour called the "YORP effect" is to blame for the ongoing demise of Gault, which could vanish

(ESA/Hubble/Business Insider)The team determined an odd behaviour called the "YORP effect" is to blame for the ongoing demise of Gault, which could vanish

The YORP effect is named after four scientists that helped lead to its discovery: Ivan Yarkovsky, John O'Keefe, Vladimir Radzievskii, and Stephen Paddack.

What powers it is sunlight. When we step outside, light from the Sun feels warm on our skin, but not like a force powerful enough to physically move us. Yet in the vacuum of space, things behave differently: There's no friction, and objects can orbit a star and persist for millions if not billions of years.

Even on human-made objects, like a thin reflective sheet, sunlight can generate enough force to propel a vehicle through space. (Scientists are currently exploring how to mimic that effect by shooting powerful laser beams at tiny spacecraft to zoom them toward other star systems at a fraction of light-speed.)

The YORP effect describes a phenomenon in which sunlight hits an asteroid unevenly, or part of the rock's surface preferentially absorbs that energy. In that case, the disparity can gradually accelerate a comet's spin.

Over time, that can lead the space rock to start spinning so fast that it rips itself apart.

That, the researchers figured, could explain why Gault grew tails so far from the Sun.

The effect is something like a parent swinging a kid around by her arms; once the parent rotates fast enough, the kid will eventually lift off the ground.

In the case of Gault, Hubble's images – plus follow-up observations by telescopes on Earth – suggested that the asteroid was spinning about once every two hours. The researchers calculated that this was fast enough to counteract Gault's gravity at the surface, allowing dirt and dust to lift off or tumble.

But what caused Gault's sudden outburst and tail formation in late 2018, after untold years of inactivity?

"Even a tiny disturbance, like a small impact from a pebble, might have triggered the recent outbursts," Jan Kleyna, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii and the study's lead author, said in a press release.

"It could have been on the brink of instability for 10 million years."

Hainaut said the long-term future of Gault is unknown. It might eventually break apart into two big chunks, or the rubble might glue itself back together under its own gravity, forming a newly shaped asteroid.

"In all cases, this will release a lot of dust, which will be spectacular," Hainaut told Business Insider in an email. "The radiation pressure from the Sun will disperse the dust, leaving either the new Gault or the binary/multiple system behind."

Given the number of asteroids in the solar system, Kleyna, Hainaut, and their colleagues now expect ever-improving all-sky survey telescopes to see sudden outbursts like Gault's about once a year.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: