It's hard to spot from Earth, but the Moon is shrinking in size as it continues to cool down.

At about 45 meters (more than 150 feet) every few hundred million years, it's hardly a rapid change, though a new study by researchers in the US suggests it might be enough to be responsible for landslides and quakes near the lunar South Pole.

What makes this research particularly important is that the study area happens to be where NASA is thinking of landing astronauts in the future. If we're going to build a space station on the Moon, it's best not to put it right in a geologically unstable zone.

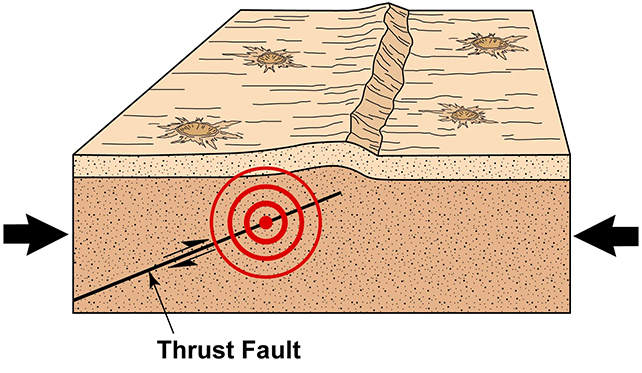

"Our modeling suggests that shallow moonquakes capable of producing strong ground shaking in the south polar region are possible from slip events on existing faults or the formation of new thrust faults," says planetary scientist Tom Watters from the Smithsonian Institution.

"The global distribution of young thrust faults, their potential to be active, and the potential to form new thrust faults from ongoing global contraction should be considered when planning the location and stability of permanent outposts on the Moon."

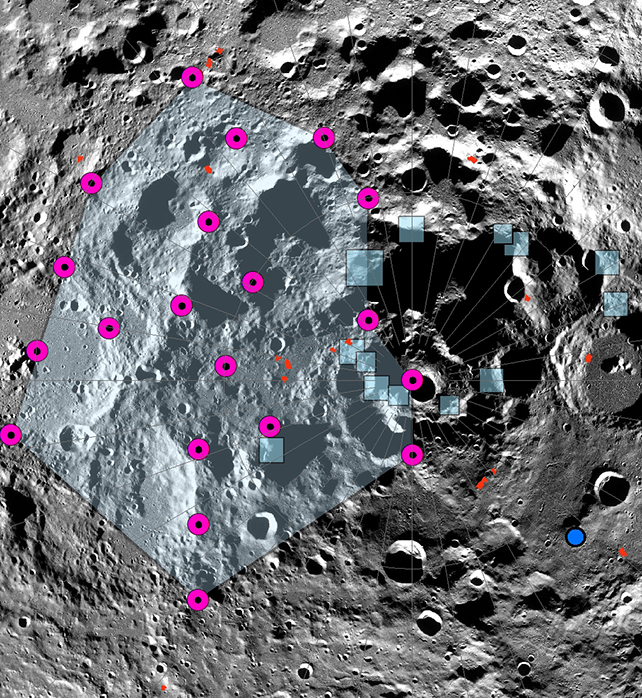

This study focused on what are known as lobate scarps, extended ridges that scientists think are caused by tectonic activity. Recent imagery from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was analyzed in tandem with recordings from the seismometers put in place during the Apollo missions, which operated until 1977.

The analysis showed that one of the most powerful moonquakes ever recorded by the Apollo seismometers, a magnitude 5 quake lasting several hours, could well have been caused by one of the lobate scarps spotted near the Moon's South Pole – and on the Moon, it doesn't take much to trigger a serious landslide.

"You can think of the Moon's surface as being dry, grounded gravel and dust," says geologist Nicholas Schmerr from the University of Maryland.

"Over billions of years, the surface has been hit by asteroids and comets, with the resulting angular fragments constantly getting ejected from the impacts."

"As a result, the reworked surface material can be micron-sized to boulder-sized, but all very loosely consolidated. Loose sediments make it very possible for shaking and landslides to occur."

For now, scientists are still dealing with a limited amount of data when it comes to the frequency and the location of moonquakes, but any insights – like the ones offered by the findings of this new study – are going to be useful in planning spots for future Moon landings and lunar bases.

"As we get closer to the crewed Artemis mission's launch date, it's important to keep our astronauts, our equipment and infrastructure as safe as possible," says Schmerr.

"This work is helping us prepare for what awaits us on the Moon – whether that's engineering structures that can better withstand lunar seismic activity or protecting people from really dangerous zones."

The research has been published in the Planetary Science Journal.