Australia's Great Barrier Reef might never have come to be were it not for the formation of a vast island based mostly on sand.

K'gari, also known as Fraser Island, has the honor of being the world's largest sand island, covering around 640 square miles (nearly 1,700 square kilometers) just off the southeastern coast of Queensland.

Along with the nearby Cooloola Sand Mass, the mass of forested dunes and beaches forms an unofficial base to the vast reef that sits to its north.

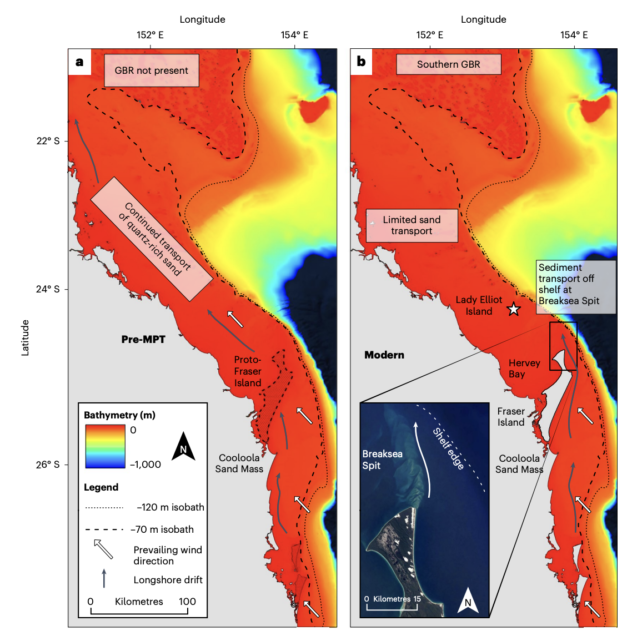

If this terrestrial 'launching pad' had never formed, researchers think the masses of sand carried northwards along the coast by ocean currents would have landed right where the reef now sits.

Quartz-rich sands have a way of smothering carbonate-rich sediments, which are necessary for coral development.

Without K'gari in the way to guide sediment off the continental shelf and into the deep, conditions would not have suited the formation of the world's largest coral reef, experts argue.

The Great Barrier Reef has a confusing origin story. It only formed half a million years ago, long after conditions were appropriate for the growth of coral.

K'gari might be the lost puzzle piece researchers have been searching for. Analysis and dating of sand from the many dunes on the 123 kilometer (76 mile) long island suggest the land mass formed between 1.2 and 0.7 million years ago, just a few hundred thousand years before the Great Barrier Reef came to be.

The island's presence probably deflected northward currents, researchers explain, providing the southern and central parts of the great barrier reef the reprieve they needed to start growing thousands of kilometers of coral.

K'gari and Cooloola themselves arose from the accumulation of sand and sediment from the south.

Amid periods of ice formation and fluctuating sea levels, researchers suspect sediment around the world 'suddenly' became exposed. In successive periods of ice melt and rising oceans, that sediment then got caught up in the currents.

Along the east coast of Australia this probably meant a long northward treadmill of soil and sand tracing the continental shelf.

A slope off the southern coast of Queensland, however, makes the perfect place for sediment to accumulate, and this is right where K'gari and Cooloola are found.

Just south of the sand masses, coral reefs are conspicuously missing.

If researchers are right, that's probably because the northward currents here are too strong. K'gari and Cooloola break up the long distance dispersal, stopping quartz-rich sands from smothering developing reefs.

"Before Fraser Island developed, northward longshore transport would have interfered with coral reef development in the southern and central [Great Barrier Reef]," researchers write.

Sediment records from the southern Great Barrier Reef support this idea. About 700,000 years ago, there appears to have been an uptick in carbonate content in sediment in this region.

Research on reefs further north is now needed as well, but at least two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef seems to owe its existence to a wall of sand to the south.

"The development of Fraser Island dramatically reduced sediment supply to the continental shelf north of the island," the authors argue.

"This facilitated widespread coral reef formation in the southern and central Great Barrier Reef and was a necessary precondition for its development."

The study was published in Nature Geoscience.