The Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine was awarded Monday to cancer researchers James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo, whose studies led to groundbreaking drugs that unleash the immune system against the deadly disease.

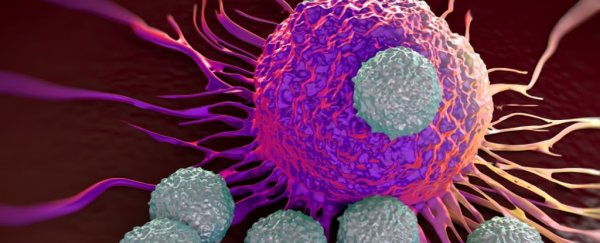

The researchers' work revolutionized cancer treatment by determining how to disengage the "brakes" that prevent the immune system from attacking cancer, said the Nobel Assembly at Sweden's Karolinska Institute, which awards the prize.

The discoveries led to a new class of drugs, called checkpoint inhibitors, that now form the fourth pillar of cancer treatments, along with surgery, radiation and chemotherapy.

Allison studied a protein that previously had been identified as a restraint on the immune system, while Honjo discovered another protein that keeps the immune system at bay.

Allison, chair of the immunology department at MD Anderson Cancer Center, said at a news conference in New York that he was "in a state of shock" after hearing from his son early Monday that he had won the award.

The honor, he added, underscored the importance of supporting basic science.

"I didn't get into this to cure cancer. I wanted to know how T cells work," he said, referring to a key part of the immune system. The 70-year-old Allison noted that his mother died of lymphoma when he was a preteen, the first of many family members to die of cancer.

The new treatments have proved especially helpful for some patients with advanced melanoma, bladder and lung cancers, sparking new hope in oncology and a billion-dollar market for the drugs.

But many patients have not benefited, and the drugs have not been found effective in treating pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma. In addition, the therapies can cause serious side effects and typically cost over US$100,000 a year.

Allison acknowledged that researchers have much more work ahead to make the new treatments help more patients - most likely by using them with other types of therapies.

"The biggest challenge," he said in an interview, "is to develop the right combinations to get the percentage of patients who respond much higher. It's just going to take a while."

Honjo, 76, speaking Monday at Kyoto University in Japan, where he works, said he began his research after a medical school classmate died of stomach cancer, according to the Associated Press.

An avid golfer, Honjo said a member of a golf club once walked up to him to thank him for the discovery that led to a treatment for his lung cancer.

"He told me, 'Thanks to you, I can play golf again'," Honjo said, according to the AP. "A comment like that makes me happier than any prize."

Scientists had worked on trying to use the immune system as an anti-cancer weapon for more than a century but scored only incremental gains until the work on checkpoint inhibitors, the Swedish academy noted.

Allison did his landmark work while at the University of California at Berkeley in the 1990s and later at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

While studying a protein known as CTLA-4 that had been identified as a brake on the immune system, he realized the implications for cancer treatment. He developed an antibody that counteracted the protein and got spectacular results in mouse studies.

In 1994, he and his co-workers performed a pivotal experiment that showed mice with cancer had been cured by the treatment. Allison pushed for years for the medication, called ipilimumab, to be developed for humans.

In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug, also known as Yervoy, for patients with late-stage melanoma. It was the first of the checkpoint inhibitors.

Meanwhile, in 1992, Honjo discovered a different protein, called PD-1, that also acted as a brake on the immune system, but through a different mechanism.

That led to the development of anti-PD-1 drugs such as pembrolizumab, also known as Keytruda, that was approved in 2014. Several similar medications have since been approved.

Former president Jimmy Carter, who was diagnosed with advanced melanoma, was successfully treated in 2015 with Keytruda, along with surgery and radiation.

The Nobel statement noted that anti-PD-1 therapies have proved more effective than anti-CTLA-4 treatments. Combining the two can be even more effective, as demonstrated in patients with melanoma.

Combining immunotherapies, however, also can lead to dangerous side effects that have to be carefully managed.

Allison, who started his career at MD Anderson in Houston and then returned there in 2012, grew up in a small town in South Texas where his country-doctor father made house calls.

He is married to oncologist Padmanee Sharma, a scientific collaborator and a specialist in renal, bladder and prostate cancers at MD Anderson.

The two are working on studies that use serial biopsies of prostate and other cancers to try to determine how the immune system reacts over time to different treatments.

With long, unruly gray hair that hangs almost to his shoulders, Allison is well known in scientific circles for his musical prowess, playing harmonica in a band called the Checkpoints.

At concerts at big cancer meetings, he growls out classics like "Big Boss Man" and "Take Out Some Insurance on Me, Baby." In 2016, he played with his idol, Willie Nelson, at the Redneck Country Club near Houston.

For years, Allison has shown up on lists of potential Nobel winners. He has won so many other awards that some sit on the floor of his crowded office.

On Monday, other researchers praised Allison's selection, saying it was long overdue.

"For 100 years, we were trying to turn on the immune system, and it didn't work for cancer, or just anecdotally," said Antoni Ribas, an immunologist at the University of California at Los Angeles.

"He figured out how to allow our immune system to attack cancer. It opened the door to a new line of therapies."

Allison went into cancer research because he always wanted to be the first person to figure something out, he said in an interview with The Washington Post last year. Early on in classes at the University of Texas at Austin, he realized that medical school wasn't for him.

"If you are a doctor, you have to do the right thing; otherwise, you could hurt somebody," he said. As a researcher, "I like being on the edge and being wrong a lot."

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.