Now, perhaps more than ever, engineers and scientists have been taking inspiration from nature when developing new technologies. This is also true for the smallest flying structure humans have built to date.

Inspired by the way trees like maples disperse their seeds using little more than a stiff breeze, researchers developed a range of tiny flying microchips, the smallest one hardly bigger than a grain of sand.

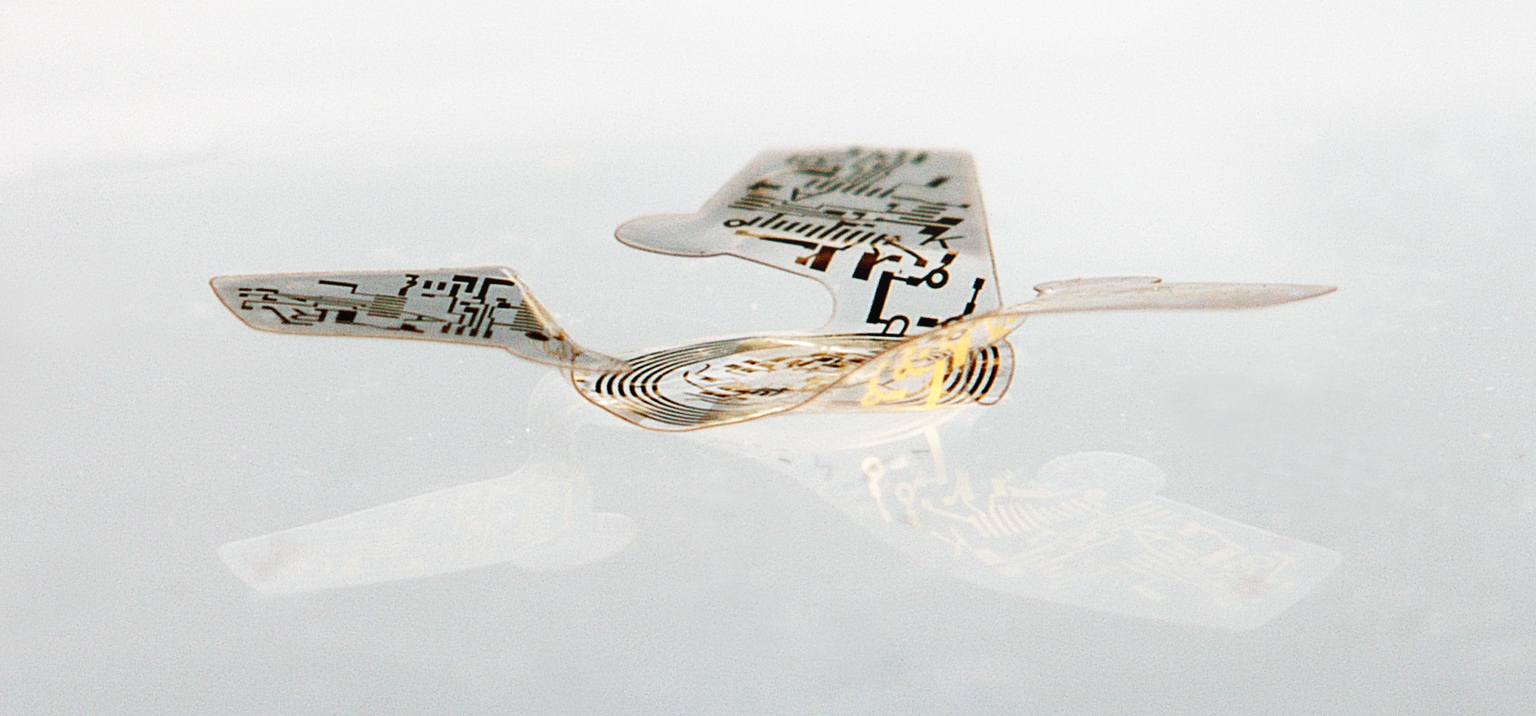

This flying microchip or 'microflier' catches wind and spins like a helicopter towards the ground.

The microfliers, designed by a team at Northwestern University in Illinois, can be packed with ultra-miniaturized technology, including sensors, power sources, antennas for wireless communication, and even embedded memory for data storage.

"Our goal was to add winged flight to small-scale electronic systems, with the idea that these capabilities would allow us to distribute highly functional, miniaturized electronic devices to sense the environment for contamination monitoring, population surveillance or disease tracking," says Northwestern's John A. Rogers, who led the development of the new device.

The team of engineers wanted to design devices that would stay in the air for as long as possible, allowing them to maximize the collection of relevant data.

When the microflier falls through the air, its wings interact with the air to create a slow, stable rotational motion.

(Northwestern University)

(Northwestern University)

"We think that we beat nature. At least in the narrow sense that we have been able to build structures that fall with more stable trajectories and at slower terminal velocities than equivalent seeds that you would see from plants or trees," says Rogers.

"We also were able to build these helicopter flying structures at sizes much smaller than those found in nature."

Rogers believes these devices could potentially be dropped from the sky en masse and dispersed to monitor environmental remediation efforts after an oil spill, or to track levels of air pollution at different altitudes.

The irony of potentially creating a new environmental pollutant while trying to mitigate the effects of another isn't lost on Rogers and his team. In the paper describing their work, the authors relay these concerns:

"Efficient methods for recovery and disposal must be carefully considered. One solution that bypasses these issues exploits devices constructed from materials that naturally resorb into the environment via a chemical reaction and/or physical disintegration to benign end products."

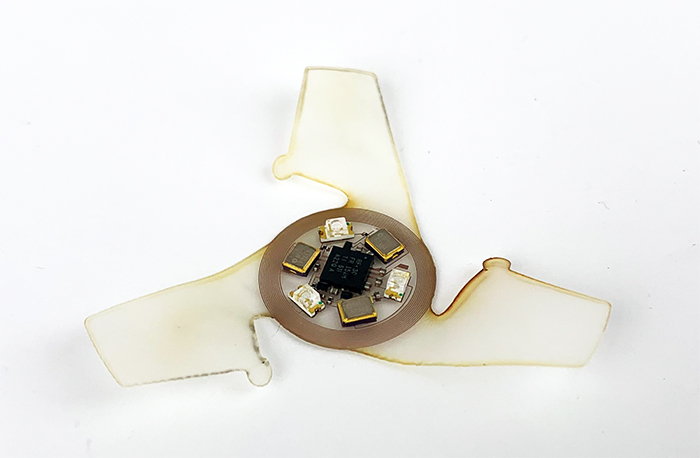

Top of a larger microflier with coil antenna and sensors to detect ultraviolet rays. (Northwestern University)

Top of a larger microflier with coil antenna and sensors to detect ultraviolet rays. (Northwestern University)

Fortunately, Rogers' lab develops transient electronics that are capable of dissolving in water after they are no longer useful. Using similar materials, he and his team aim to build fliers that could degrade and disappear in ground water over time.

"We fabricate such physically transient electronics systems using degradable polymers, compostable conductors and dissolvable integrated circuit chips that naturally vanish into environmentally benign end products when exposed to water," says Rogers.

"We recognize that recovery of large collections of microfliers might be difficult. To address this concern, these environmentally resorbable versions dissolve naturally and harmlessly."

The research was published in the journal Nature.