The Bayeux Tapestry, an enormous length of embroidered cloth depicting events culminating in the Battle of Hastings in 1066, has long been a mystery, but the once-forgotten artwork might have finally found its place.

While it's almost universally agreed that the tapestry was designed by monks who lived at St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, England, and made by a team of skilled embroideresses, we're still not totally sure why it was created, or where it was hung.

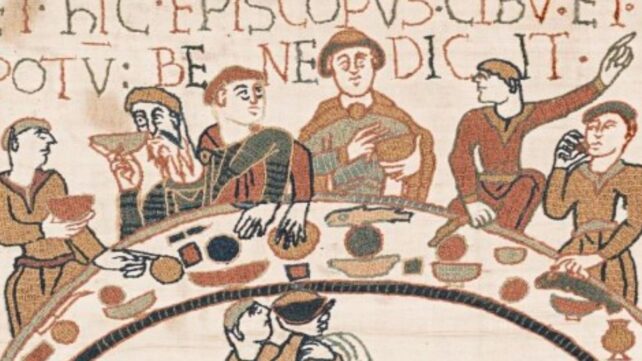

Historian Benjamin Pohl presents his theory in a new paper: The tapestry, he believes, was mealtime reading material for the monks at St Augustine's, or someplace like it.

Related: Medieval Monks Twice as Likely to Be Infected by Parasitic Worms, Study Finds

"I wondered whether a refectory setting could help explain some of the apparent and puzzling contradictions identified in existing scholarship," Pohl says, referring to the communal dining halls where monks shared meals.

"Just as today, in the Middle Ages mealtimes were always an important occasion for social gathering, collective reflection, hospitality, and entertainment, and the celebration of communal identities. In this context, the Bayeux Tapestry would have found a perfect setting."

While there is no concrete evidence that the Bayeux Tapestry was housed at St Augustine's, Pohl notes there are many clues to suggest that it may have once hung upon the abbey's refectory walls.

The tapestry's enormous size – measuring more than 68.4 meters (224 feet) long and weighing about 350 kilograms (772 pounds) – means that, for display, it would have to be mounted directly onto a solid wall.

Previously, researchers have suggested it could have always been housed at the eponymous Bayeux Cathedral (where it was found in the 15th century). But Pohl notes the vaulted bays and colonnades of the cathedral walls would have made it "one of the least suitable spaces for exhibiting the giant embroidery".

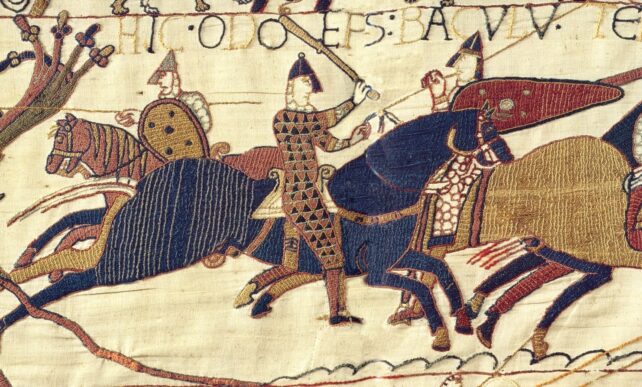

The tapestry was still likely designed for a religious audience, Pohl writes, because "its conspicuous (and perhaps deliberate) political ambiguity and lack of partisanship… seems difficult to square with the identity and self-perception of England's post-Conquest aristocracy".

Meanwhile, its various Latin inscriptions, though simple, would have required a degree of literacy uncommon among 11th-century nobles. Monks, on the other hand, would've made easy work of the tapestry's inscriptions.

A monastic audience makes even more sense in light of the strict rules that governed the monks at mealtimes: They had to maintain complete silence, even going so far as to use sign language to ask, for instance, if someone could please pass the salt. Perhaps the tapestry was akin to moral, educational mealtime entertainment.

"With the monastic community of St. Augustine's as its primary audience, the Bayeux Tapestry did not have to tell the stories of patriotism and national pride/resentment read into it by modern commentators," Pohl writes.

Instead, he suggests its narrative could be read as "one that revealed God's workings through the actions of human agents in much the same way as the episodes from scripture and other kinds of historiography/hagiography read to them during mealtimes."

Related: Medieval Monks Could Have Unknowingly Recorded The Ferocity of Volcanic Activity

The refectory at St Augustine's would have been the ideal place for hanging such an unwieldy work of art: With at least 70 meters of internal wall space, the building had more than enough room for the tapestry to hang, even if the final, missing section spanned several extra meters.

In the 1080s, a new refectory was designed for the abbey, but a series of disruptions stymied its construction. First, there was the untimely death in 1087 of St Augustine's first post-Conquest abbot, Scolland (who championed the renovation).

Then, the death of Scolland's unpopular successor, Wido, against whom the monks had openly rebelled, left the position of abbot vacant for more than a decade.

And when the role was finally filled by Hugh I, priorities at St Augustine's lay elsewhere, meaning the refectory was not completed until the 1120s.

Perhaps, amidst this drawn-out renovation, Pohl suggests, the tapestry was packed away and receded from the monastic community's collective memory.

"Consequently, the Tapestry might have been put in storage for more than a generation and forgotten about until it eventually found its way to Bayeux three centuries later," Pohl says.

This could explain how it managed to survive various disasters that struck the abbey – a fire, an earthquake, and a 13th-century renovation – and also its absence from any records until it turned up in a Bayeux inventory in 1476.

"There still is no way to prove conclusively the Bayeux Tapestry's whereabouts prior to 1476, and perhaps there never will be," explains Pohl.

"But the evidence presented here makes the monastic refectory of St Augustine's a serious contender."

The full Bayeux Tapestry can be viewed on Wikipedia, here.

The paper is published in Historical Research.