It's not easy being a soldier or a spy: you have to immerse yourself in dangerous situations, assess intelligence in the field, speak foreign languages, and handle all kinds of technical equipment and weaponry.

Learning how to do all of that takes a lot of training, which is why the research wing of the US Department of Defence wants to figure out ways to make its workers learn these vital skills quicker – even if they have to zap them to do it.

To explore these possibilities, the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has just awarded more than an estimated US$50 million in funding to eight teams looking into how electrical stimulation of the nervous system can help facilitate learning.

The four-year program, called Targeted Neuroplasticity Training (TNT), aims to identify safe and optimal neurostimulation methods that can activate what's called synaptic plasticity – the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken, and by doing so, learn how to do new things and make memories.

"The Defence Department operates in a complex, interconnected world in which human skills such as communication and analysis are vital, and the Department has long pushed the frontiers of training to maximise those skills," says bioengineer Doug Weber, who manages the TNT program.

"DARPA's goal with TNT is to further enhance the most effective existing training methods so the men and women of our Armed Forces can operate at their full potential."

And DARPA has a pretty specific target for that "full potential" too, wanting to see a 30 percent improvement in learning rates over existing training by the time the four-year program is up.

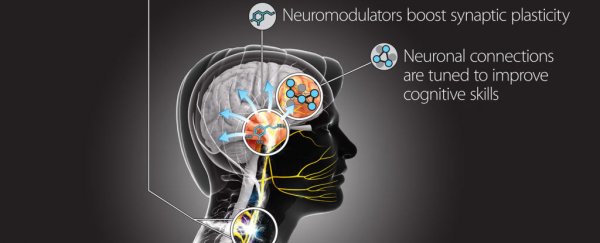

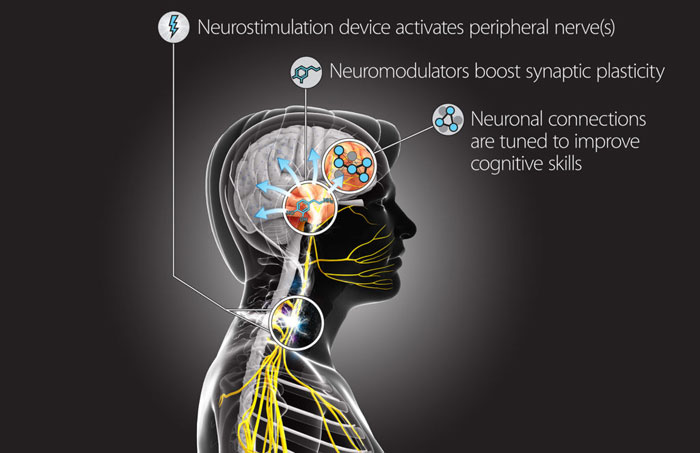

Whether that can be achieved remains to be seen, but the hope is that by delivering electrical pulses to the nervous system, the researchers can figure out how to release certain key neurochemicals to modulate neural connections in the brain that could have an impact on synaptic plasticity.

Tweaking the brain like this can "influence cognitive state – how awake you are, or how much attention you're paying to something you're viewing or performing," Weber told Emily Waltz at IEEE Spectrum.

Across the eight teams involved in the program, researchers will be conducting a range of experiments on both animals and human volunteers, looking at how different nerves may end up affecting learning prospects.

A team from Arizona State University is investigating how neurostimulation could affect surveillance, reconnaissance, and marksmanship skills, while researchers from John Hopkins University are investigating the effects on language learning.

DARPA

DARPA

At the University of Florida, scientists will study how stimulation of the vagus nerve – which connects the brain and the gut – impacts our perception, decision-making and spatial navigation.

Vagal nerve stimulation is already being used by some scientists to prevent seizures and treat depression, but is still poorly understood.

"There are clinical applications, but very little understanding of why it works," says one of the team, neuroscientist Jennifer L. Bizon.

"We are going to do the systematic science to understand how this stimulation actually drives brain circuits and, ultimately, how to maximise the use of this approach to enhance cognition."

While previous DARPA brain research in this area has mostly looked at how to restore lost functions – such as restoring memory in people who have suffered traumatic brain injuries – the TNT program is focussed purely on advancing people's natural capabilities.

If the venture succeeds, it's likely that soldiers and spies won't be the only beneficiaries.

"You can envision that if we could come up with a kind of way to non-invasively control brain chemistry with high fidelity, that there's a lot of human conditions we could improve," one of the researchers, biomedical engineer Justin Williams from the University of Wisconsin, told STAT, citing the examples of tackling learning disabilities in children, or memory disorders in adults.

But eventually the benefits will also be offered to enlisted soldiers – perhaps as an optional neurostimulation component at boot camp training.

"There are elite performers who are eager for anything and everything that would give them an additional boost or benefit," Weber told IEEE Spectrum.

"For these individuals, I think it would be fantastic if we can help."