Even the words we use to express our connection to nature are dwindling as the demands of modern life isolate us from the non-human world, according to a new study by psychologist Miles Richardson of the University of Derby in the UK.

As a proxy for humans' connection to nature across time, Richardson turned to books, specifically data lifted from Google Books Ngram Viewer for the period 1800-2019. He mapped the frequency with which authors used 28 words associated with nature: words like river, meadow, beak, coast, and bough.

He avoided species names because, he reasons, they "tend to be more technical or impersonal… [and] are also more susceptible to reflecting wildlife population trends or being influenced by factors like the proliferation of identification guides."

Related: Kids Need to Spend Time Alone Outdoors to Really Bond With Nature, Study Finds

"These words reflect what people noticed, valued, and wrote about," Richardson writes in a blog post. "And when their use is plotted over time, a clear decline of around 60 percent is revealed, particularly from 1850, a time when industrialization and urbanization grew rapidly."

This approach has many limitations: bias arises, for instance, from the selection of texts available in the Google dataset, and from the words Richardson chose as signifiers of the natural world (for instance, the exclusion of more liminal keywords, where nature overlaps with human life, like 'crops' or 'garden').

But it's not the only study that's found references to nature have been disappearing from our culture: researchers from the London Business School came to similar conclusions in their 2017 analysis of fiction books, song lyrics, and even film storylines.

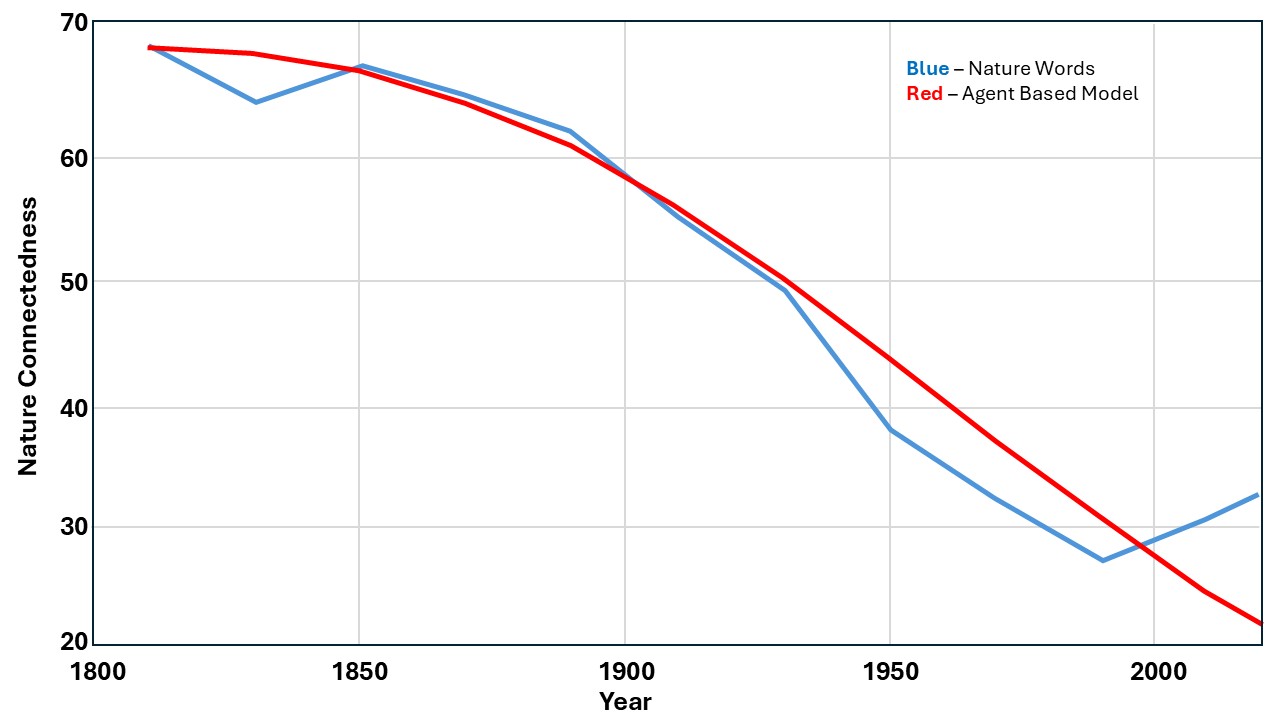

Interestingly, the book data closely correlates with a computer model Richardson developed to simulate how our connection with nature has declined from 1800 to 2020.

"Here's the remarkable part: the model (red line), built from the ground up to simulate human–nature interactions, closely mirrored, with less than 5 percent error, the actual decline in nature word use," Richardson writes.

"Despite the uncertainties of using language as a proxy, the fit was striking."

It suggests the simulation could be close to the truth. If so, our connection to nature has declined by more than 60 percent in the past two centuries.

This simulation showed a substantial decline in nature connectedness driven primarily by a breakdown across generations. It shows the importance of sharing a connection with nature with children, something that's easier said than done as our surroundings become increasingly urbanized and ecologically degraded.

"Nature connectedness is now accepted as a key root cause of the environmental crisis," Richardson told Guardian journalist Patrick Barkham. "It's vitally important for our own mental health as well. It unites people and nature's wellbeing. There's a need for transformational change if we're going to change society's relationship with nature."

The research was published in Earth.