Fossilised cosmic dust has been found in a completely new source - the world famous white cliffs of Dover in England. And they could help us learn more about how our solar system evolved.

"The iconic white cliffs of Dover are an important source of fossilised creatures that help us to determine the changes and upheavals the planet has undergone many millions of years ago," said lead researcher Martin Suttle of Imperial College London.

"It is so exciting because we've now discovered that fossilised space dust is entombed alongside these creatures, which can also provide us with information about what was happening in our solar system at the time."

Cosmic dust, also known as micrometeorites, is made up of microscopic particles that originated from space, and it's all over our planet.

An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 tonnes (22,000 to 33,000 tons) of the stuff falls to Earth every year, but given its size, it's pretty hard to locate, even if it is identifiable by chemical composition, shape and crystal structure.

Identifying fossilised cosmic dust is one step more difficult again. This is because of the fossilisation process, which replaces the original minerals of the dust sample with other materials. Identifying the dust based on its composition doesn't apply.

Imperial College London

Imperial College London

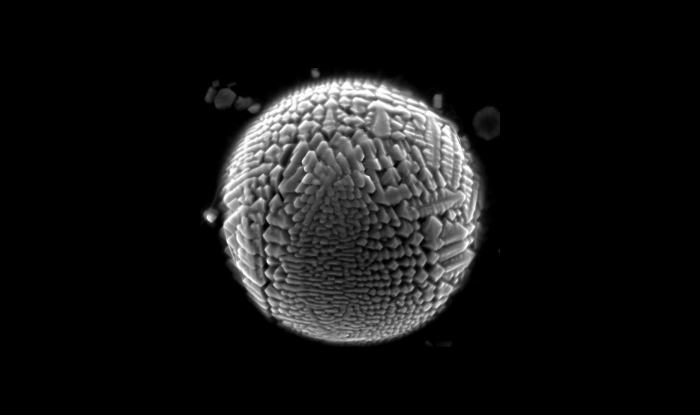

By shape and crystal structure alone, as shown in the image above, and comparing the samples with cosmic dust found in Antarctica, the team found 76 fossilised micrometeorites in the white chalk. They date back to the Coniacian age of the Upper Cretaceous, around 87 million years ago.

Although they may be chemically altered, the samples offer new avenues for studying cosmic dust, due to the exceptional preservation of their structure. Antarctic samples, found preserved in snow and ice, are often degraded by their environment, and are much harder to date accurately.

The abundance of samples found in the chalk and the high quality of their preservation suggests that fossil micrometeorites are relatively common, and can be located and studied in detail.

This means we might be able to learn more about events in the solar system up to 98 million years ago, such as collisions between asteroids, which would have produced cosmic dust. Cosmic dust records for this period have been difficult to find - until now.

"The discovery … demonstrates that extraterrestrial dust, preserved in marine sediments, can be successfully extracted and identified even where complete secondary replacement (fossilisation) has occurred," the researchers write in the paper.

"Until now geochemical criteria have been required for the positive identification of cosmic dust; however, because complete secondary replacement can occur, fossil micrometeorites imply new identification criteria, independent of geochemical metrics."

The research has been published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.