Around the world, women outlive men by an average of around 5.4 years. A distinction in life expectancy between sexes is surprisingly common among other mammals, too, though it's not fully understood why.

An international research team has now uncovered the evolutionary roots of this phenomenon, with a detailed study of sex differences in the lifespans of mammals and birds.

Biology defines sex in many different ways – and the human concept of gender adds even more nuance to these terms. In this study, sex was defined by the presence of specific chromosomes.

Related: Darwin Made an Error About Sexual Selection, Research Reveals

Among mammals, females are defined as having two X chromosomes, while males have only one X and one Y. Male mammals are therefore heterogametic: each of their chromosomes is a different shape, rather than two of the same.

In birds, on the other hand, females are the heterogametic sex: they have one Z and one W chromosome, while males have two Zs.

Scientists have long suspected these chromosome patterns may underlie the differences in lifespan between males and females, and the new research supports that theory.

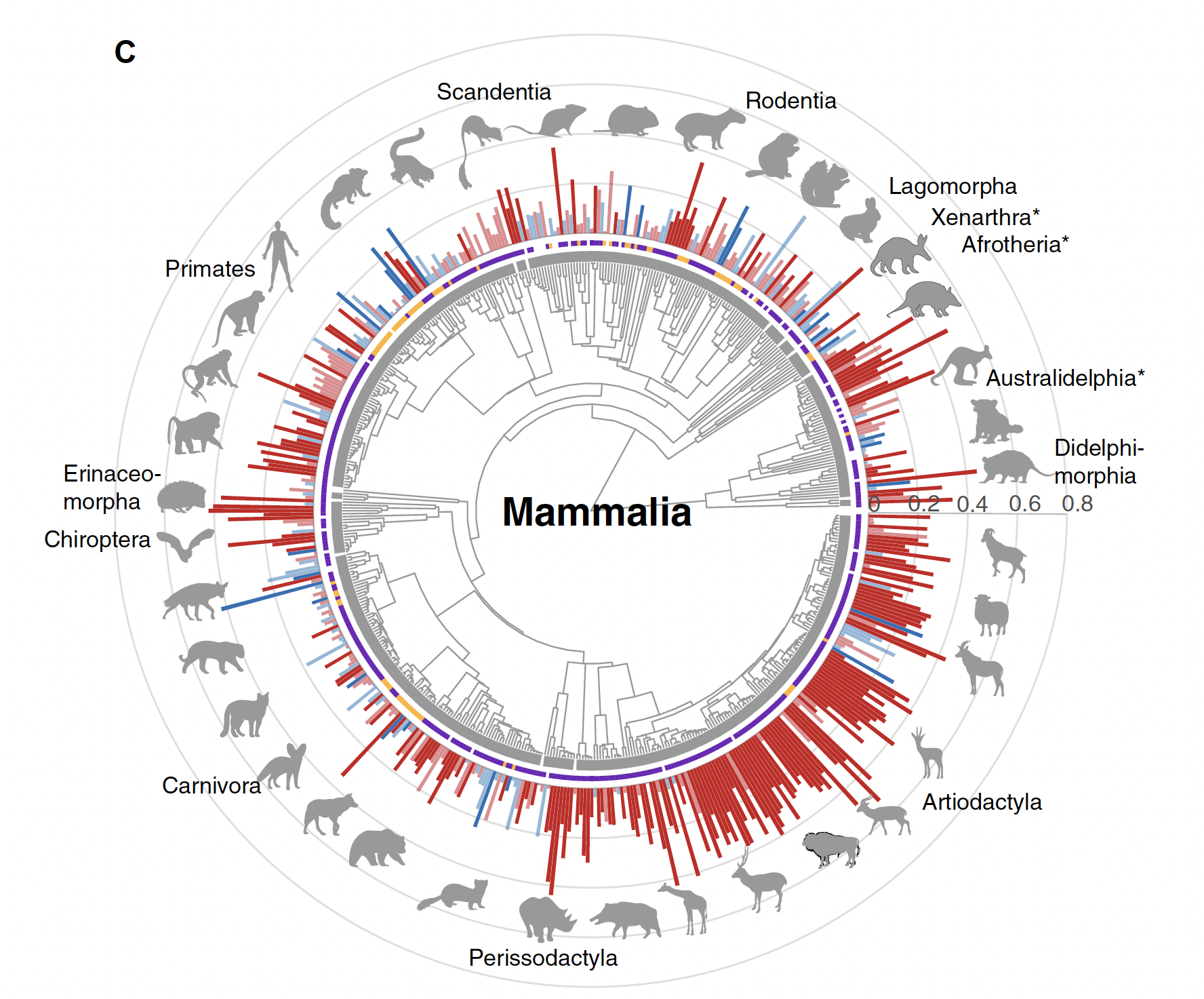

The team, led by primatologist Johanna Stärk from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, analyzed adult life expectancy within zoo records for more than 1,176 species of mammals and birds.

Among 72 percent of the mammal species in the study, females lived about 12 percent longer than males. But among 68 percent of bird species, males outlived females – by an average of about 5 percent.

They also examined published data on wild populations for 110 of those species to validate their findings in natural settings.

That same pattern appeared, even more pronounced: in mammals, the female advantage was on average 1.5 times greater than in zoos; in male birds, the advantage was five times greater than in zoos.

Without the carefully controlled diet and round-the-clock vet care that zoo animals enjoy, it may be unsurprising that there was greater variation in life expectancies for wild animals.

The fact that the lifespan gaps persisted in zoo environments – where other pressures like predation, competition, and harsh climate are somewhat alleviated – suggests sex chromosomes are at least partly responsible for the shorter lifespans of some heterogametic sexes.

But that wasn't the case for all species.

"Some species showed the opposite of the expected pattern," says Stärk. "For example, in many birds of prey, females are both larger and longer-lived than males."

She and her team suggest that adult life expectancy is "likely influenced by a combination of environmental and genetic factors."

"While our results partially support the heterogametic sex hypothesis, heterogamy alone cannot explain the breadth of variation in adult life expectancy differences found here," they write.

Among non-monogamous mammals, for instance, males tend to die earlier than females because there's more competition and a greater risk of death.

Meanwhile, many birds are monogamous, which means males may live longer in part due to lower competition. Males and females tended to enjoy a greater similarity in lifespans in monogamous species, while polygamous species and those with sex-dependent size differences tended to have shorter-lived males and longer-lived females.

"Even in zoos, where environmental pressures are largely reduced, precopulatory sexual selection seems to play a fundamental role in shaping sex differences in life expectancy in mammals and birds," the researchers note.

They also found that a parent involved in raising offspring tends to lead a longer life: for instance, female primates care for their young until they are sexually mature, so their longevity is important for the next generation's survival.

Together, these results suggest adult life expectancy is the result of a complex interaction of animal behaviors and genetics. But even though environmental factors can alter the degree of difference between sexes, at a population level, it seems some difference will always persist.

This research was published in Science Advances.