Scientists working in the Andes Mountains in Patagonia have been presented with a puzzle: Mice from the same species are growing to larger sizes on the western side of the mountains compared to the eastern side.

Now a new study suggests a solution to the mystery.

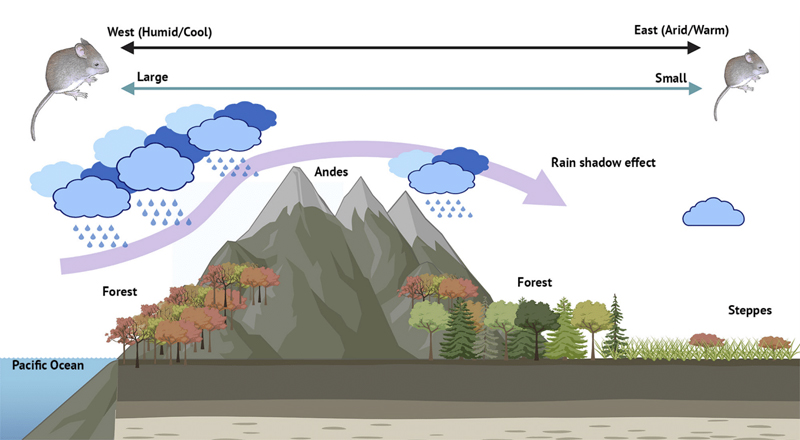

It seems that thanks to the rain shadow effect – where clouds are pushed higher as they pass over the mountains, triggering rain on the first side they hit – the mice on the western slopes have more food to eat, causing the extra growth.

The rain shadow effect is a commonplace phenomenon that happens across many mountain ranges, leaving one side drier than the other.

However, scientists are still learning how this leads to changes in the environment and local wildlife.

"There are a bunch of ecogeographic rules that scientists use to explain trends that we see again and again in nature," says mammalogist Noé de la Sancha, from DePaul University in Chicago.

"With this paper, I think we might have found a new one: the rain shadow effect can cause changes of size and shape in mammals."

The mice in question are from the shaggy, soft-haired Abrothrix hirta species, and the team analyzed 450 mouse skulls – using roughly an even split between male and female skulls – to assess the differences in size.

After that, they set about trying to find an explanation, looking at possible correlations between size and latitude, altitude, temperature, or precipitation.

In the end, it was longitude – how far east or west the mice lived – that matched up with the variations in size. Add in what's known as the resource rule, where more resources tend to lead to larger animals, and the researchers almost had their answer.

There was one question remaining: Why were there more resources to the west?

The team eventually realized it was the rain shadow. Water is picked up from the ocean and blown towards the mountains, and as the air rises it gets colder. That triggers rain, which can mean much more of it on one side of the mountain range.

"Essentially, one side of the mountain will be humid and rainy, and the other will have cold, dry air," says de la Sancha.

"On some mountains, the difference is extreme. One face can be a tropical rainforest, and the other side will be almost desert-like."

There are other natural rules like this. Take Bergmann's rule, for example, which links larger animals in the same species with colder environments – in that case, it's because having a thicker body helps to retain heat better.

The newly established link brings with it new concerns relating to climate change. Shifts in temperature can cause shifts in precipitation levels, which scientists now know affects the morphology of these mice and potentially other animals. Changes in weather patterns could well affect the amount of food available to eat.

While the future remains unclear, it's important to gather as much data as possible so we can understand the current and potential implications of climate change – and that data now includes how locations on a mountain are related to animal size.

"It's exciting, because it could potentially be something that's more universal," says de la Sancha. "We think it may be more of a rule than an anomaly. It'd be worthwhile to test it on lots of different taxa."

The research has been published in the Journal of Biogeography.