An ancient society that once called the Sahara desert home survived for nearly a millennium without water from regular monsoons or continuously flowing rivers.

The forgotten civilization was known as the Garamantes to the Romans, and it was the first urbanized society known to establish itself in a desert.

Despite the location, its people not only survived, they thrived, squeezing every drop of life they could from beneath the sand.

Using slaves to build tunnels and harvest groundwater, free residents in the "Kingdom of the Sands" achieved a standard of living that experts say went unmatched in the region.

Researchers from Ohio State University and Bowling Green State University in the US have now shown that while the incredible effort certainly took smarts, a lot of luck was involved, too.

It was all going great, in fact, until that luck ran out.

The recent research is based on past archaeological studies and hydrological analysis, and the findings were presented at the Geological Society of America's 'Connects' conference this October.

Through the eyes of ancient historians, the Garamantes were a people mostly made up of desert barbarians. When archaeologists first unearthed the Garamantian capital, Garama, in the 1960s, the civilization was still assumed to be small and simple. The Sahara was considered too arid and unforgiving to support much more than that.

Over the years, however, evidence began to emerge that suggested this ancient society was much more advanced and successful than experts once assumed, covering more than 180,000 square kilometers (70,000 square miles) with a capital consisting of 4,000-some people.

The key to its success was a vast underground sandstone aquifer, which today is considered one of the largest in the world.

This vital water source from wetter times gone by was able to support towns and large settlements in the now arid region, providing a home to farmers, cattle herders, engineers, merchants, and slaves.

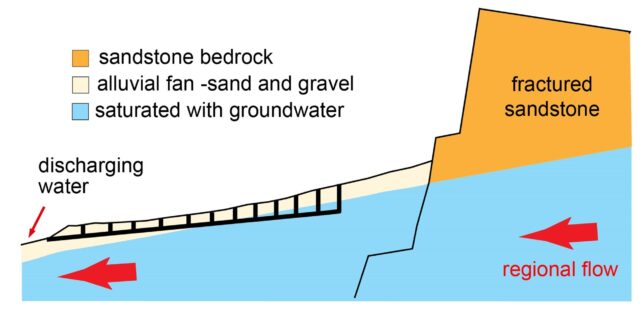

To reach the precious liquid below ground, the Garamantes society spent centuries forcing slaves to dig 750 kilometers of vertical shafts and underground tunnels, called foggaras, which were inclined to poke just below the water table, allowing the liquid inside to run downhill.

The technique was acquired from societies in Persia. Yet unlike in Persia, aquifers aren't recharged by snow melt in the Sahara, which means the same strategy really shouldn't have worked.

Nevertheless, the Garamantes had luck on their side.

Their aquifer had a flow system that moved water from deep below ground to the base of a hill, where more than 500 foggaras were built, some extending up to 4.5 kilometers in length.

Like tipping a cup to get water through a straw, it allowed the Garmantes civilization to irrigate crops for nearly a century, as even a bit of rainfall could help recharge the system.

That bliss couldn't last forever. Inevitably, the water level of the aquifer dropped below the foggaras. To reach it once again would have required many more tunnels to be built and many more slaves to do the building.

With food and water shortages already taking hold, however, trading for slaves or acquiring them through warfare would have become ever more difficult.

The fate of the Garamantes all those years ago is a warning for us today. In many parts of the world, water tables are shrinking as human demand increases and climate change takes its hold.

These resources won't last forever.

"Societies rise and fall at the pleasure of the physical system, such that there are special features that let humanity grow up there," says earth scientist Frank Schwartz from Ohio State University.

"As you look at modern examples like the San Joaquin Valley, people are using the groundwater up at a faster rate than it's being replenished. If the propensity for drier years continues, California will ultimately run into the same problem as the Garamantians."

The paper was presented at the 2023 Geological Society of America Connects Meeting.