Scientists thought the Wilmington blind‐thrust fault that runs deep under the Los Angeles region had been dormant since the Late Pliocene era, millions of years ago.

But a new study reveals that it's very much alive, and capable of generating the kind of 6.4-magnitude earthquakes that could cause serious damage in such a populous area.

The devastating 1994 Northridge earthquake was also caused by a blind-thrust fault, which are not visible from the surface, and registered a 6.7, within the range of what researchers estimate the Wilmington blind‐thrust fault could generate on its own.

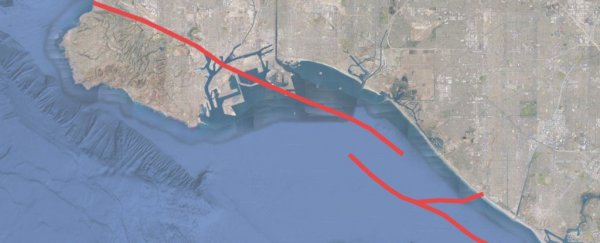

The fault is about 12 miles (19 kilometers) in length and runs diagonally northwest to southeast across the southwestern Los Angeles Basin, though related segments to the north and south lengthen the span of it to about 34 miles (55 kilometers).

It runs beneath the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, both of which are vital shipping centers for the state and the country.

But the authors of the study, which was published last month in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, say that the fact that its activity wasn't discovered sooner is really nobody's fault.

The Wilmington fault is moving more slowly than others in the region, which made it harder to detect its movements, said Franklin Wolfe, a doctoral fellow at Harvard University who led the study.

The formation's existence had been known since the 1930s, thanks to its presence near Southern California's immense Wilmington Oil Field. The oil industry had extensively studied the deepest and most ancient layers of rock, which showed folding indicative of a dormant fault line, Wolfe explained.

But they hadn't looked at the younger, uppermost layers, which didn't contain precious oil but turned out to bear subtle signs of seismic activity.

The first hints that something might be going on began almost two decades ago, when another one of the study's authors, Daniel Ponti of the US Geological Survey, began researching those layers as part of a water study in the area.

Ponti and his team noticed that the upper layers of rock bore the same telltale folds as the deeper ones below, which had been molded by earthquakes on the Wilmington blind‐thrust fault millions of years ago, indicating that the fault had been active far more recently than previously thought.

They first published their findings in 2007 but needed more research to know what the folds meant.

For the new study, researchers at Harvard University and the USGS combined extensive data compiled by the oil industry of the deepest, oldest layers of rock in the area with new research from the USGS to create a comprehensive picture of the geology around the fault.

After using 2-D and 3-D modeling technology, they were able to create a comprehensive picture of the fault and estimate its potential strength.

The good news, researchers say, is that the discovery of the Wilmington fault's activity doesn't necessarily increase the earthquake hazard level in the Los Angeles Basin.

The bad news: That's because there are already so many known active faults in Southern California and the state, and several of them are capable of producing damaging earthquakes.

Ponti and Wolfe say that further study of the fault is essential to determine whether it is connected to others in the region, as earthquakes on one fault can sometimes influence activity on another. But in the meantime, they say that the discovery shouldn't worry Los Angeles residents about earthquakes - more than usual, that is.

"If you live pretty much anywhere in California, you're at earthquake risk," Ponti said. "We can refine that estimate a little better, but it doesn't change the fact that you need to be prepared for a major earthquake in your area."

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.