Have you ever seen fine water condensation on a transparent surface shimmer like a rainbow? Scientists have now figured out exactly how it happens - and have used this new knowledge to make water droplets produce a dazzling array of colours.

If the droplets are on a transparent surface, and lit by a single lamp, they'll shimmer. Moreover, droplets of the same size produce the same colour.

The trick lies with way the shape of a water droplet interacts with light, producing the different wavelengths we perceive as colour.

When light enters the droplet, it bounces around the interior surface before re-emerging. Since the size of the droplet has an effect on the bouncing, it influences the resulting colour we see.

(MIT)

(MIT)

This phenomenon, whereby the structure of an object produces colour is called, fittingly, structural colour. It's common in nature - a butterfly's wings or a chameleon's skin, for instance, look colourful to us as light bounces off their microstructures.

By studying how light interacts with water droplets, engineers have developed a model for predicting the colour a water droplet will produce under specific structural and optical conditions.

The project began when Amy Goodling and Lauren Zarzar of Penn State were studying droplet emulsions. They noticed the droplets appeared blue, and asked MIT mechanical engineer Mathias Kolle for an explanation.

At first, the researchers thought it might be similar to the refraction mechanism that produces rainbows from spherical water droplets.

"Initially we followed this rainbow-causing effect," said MIT engineer Sara Nagelberg. "But it turned out to be something quite different."

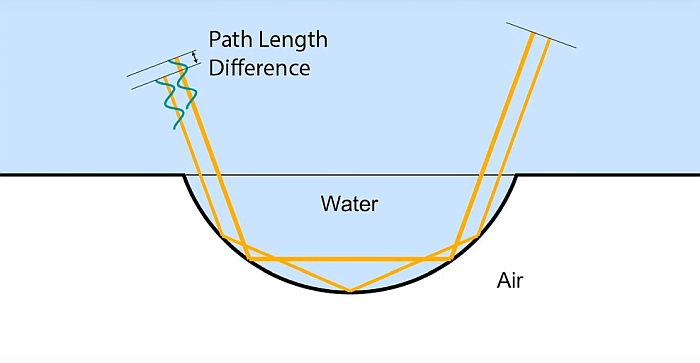

The droplets resting on a surface are hemispherical, rather than spherical like rainbow-producing mist, and that's a critical difference. That hemispherical shape allows for a phenomenon that's not possible with spheres.

It's called total internal reflection - when light enters a dense medium from a less dense medium at a high angle, it results in 100 percent of the light being reflected into that denser medium (in this case, it was the glass surface of the petri dish), without any refraction.

When a light ray enters a droplet, it will bounce around in there before exiting at another angle. How the light rays combine on exit is one factor that contributes to the production of colour.

Other factors that affect the resulting colour include the size, curvature, and refractive index of the droplet, as well as the light used. The predictive model took all of this into account.

Then, the team tested it, spraying a uniform layer of droplets onto a petri dish or transparent film, shining a bright light on it, and moving the camera around. This last part changed the angle at which the reflected light would enter the eye, thus affecting the colour.

The size of the droplet made a difference, too. Larger drops produced more red colours, which are produced by longer wavelengths, while smaller drops tended towards blue, produced by shorter wavelengths.

Additionally, the team experimented with a coating to produce droplets of different sizes on a single film, to determine whether multiple colours could be achieved (they could), as well as making solid transparent microstructures in the shape of droplets to determine if the model could also be applied to these (it could).

With these results, the team thinks we could actually produce pigments that don't rely on chemical dyes.

"Synthetic dyes used in consumer products to create bright colours might not be as healthy as they should be. As some of these dyes are more strongly regulated, companies are asking, can we use structural colours to replace potentially unhealthy dyes?" Kolle said.

With this model, maybe we can.

The research has been published in Nature.