Just like our own Milky Way, most of the universe's galaxies are shaped like spirals, with long swirling arms of cosmic matter stemming from a bright core.

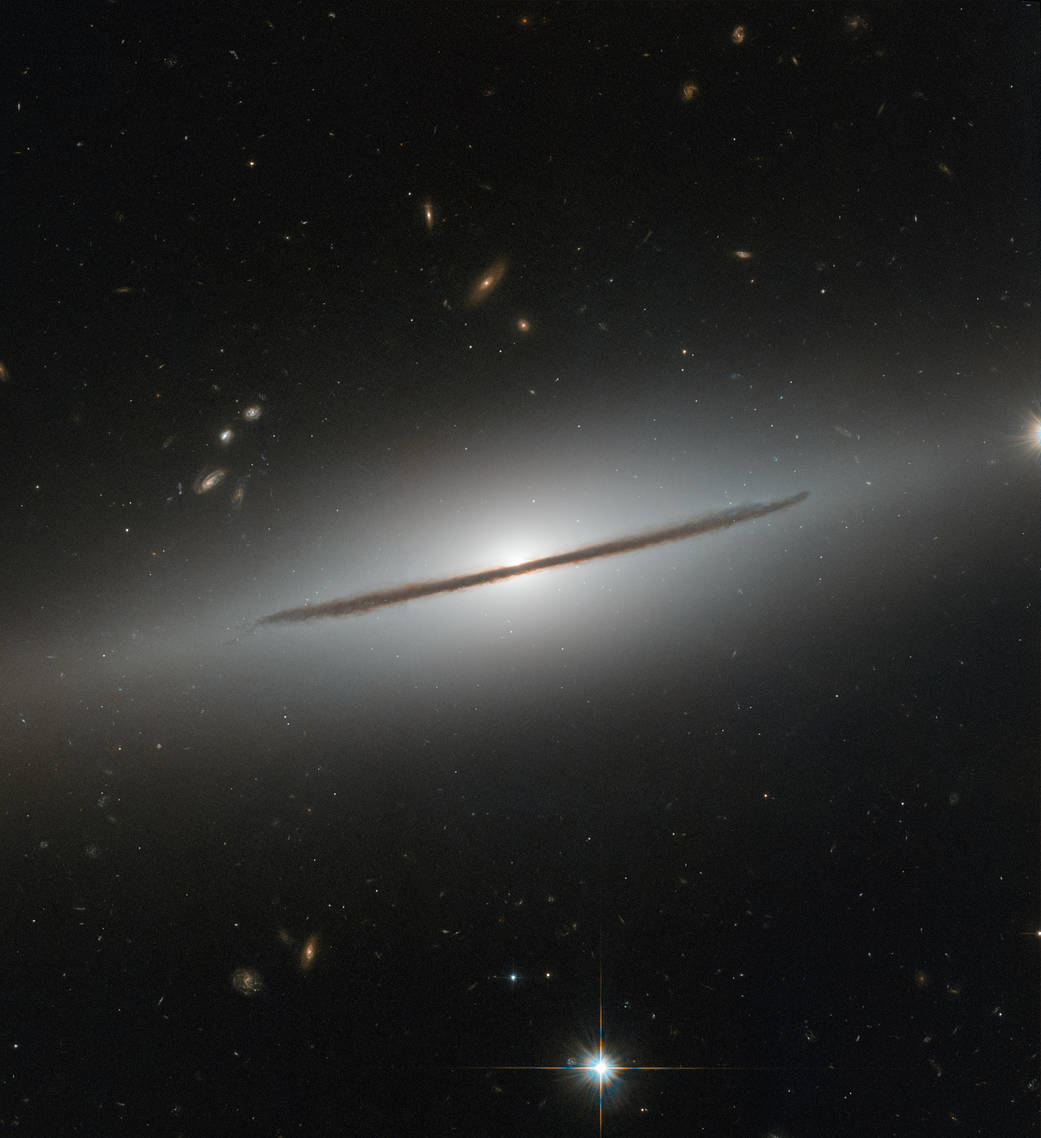

Still, they don't always appear like that to us. When viewed from the side, spiral galaxies can look deceivingly linear, as a new image from the Hubble Space Telescope demonstrates.

"Believe it or not, this luminous streak is a spiral galaxy like our Milky Way," explains the European Space Agency, which operates the telescope along with NASA.

On the edge of a galaxy. ✨

— NASA (@NASA) August 2, 2019

Believe it or not, this luminous streak is a spiral galaxy like our Milky Way. Because observatories like @NASAHubble have seen spiral galaxies at every kind of orientation, astronomers can tell when we see one from the side: https://t.co/D47pHMuu0c pic.twitter.com/HcWFvPESoM

The galaxy in this case is NGC 3432, which is located in the Leo Minor constellation, a mere 45 million light years away, which is quite close considering the size of the universe!

If you think of it like a disc, with its arms and bright center only viewable from each face, then the above image starts to make more sense. NGC 3432 appears like a thin strip because it is oriented directly edge-on to us from our vantage point here on Earth.

"Dark bands of cosmic dust, patches of varying brightness and pink regions of star formation help with making out the true shape of NGC 3432 — but it's still somewhat of a challenge!" the ESA caption admits.

A face-on spiral galaxy, called NGC 3982. (ESA/NASA)

A face-on spiral galaxy, called NGC 3982. (ESA/NASA)

In its two decades of work, the Hubble Space Telescope has observed spiral galaxies at every kind of orientation, from face-on to tilted angles, and this is what ultimately allows astronomers to recognise a side-ways spiral galaxy when they see one.

In May of last year, Hubble caught a glimpse of a nearly edge-on spiral galaxy called NGC 1032 that was said to resemble a wizard's staff set aglow.

(ESA/NASA)

(ESA/NASA)

While actually seeing the arms and nuclei of a spiral galaxy provide a wealth of detail - especially about star-forming regions of glowing, newborn blue star clusters, and dust lanes of raw material for future generations - the edge-on view is necessary if astronomers are to understand the full three-dimensional structure.

"This gives astronomers an overall idea of how stars are distributed throughout the galaxy and allows them to measure the 'height' of the disk and the bright star-studded core," a statement from ESA explains.